|

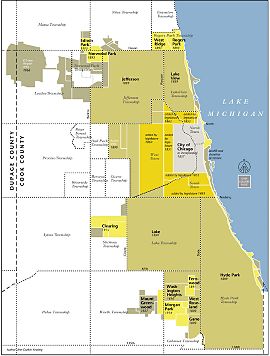

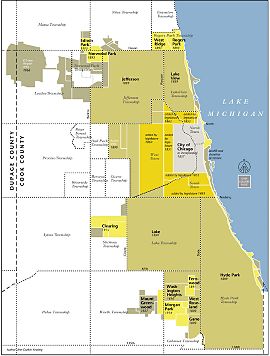

The Expanding City

|

The first chapter of the

Plan of Chicago

opens with the premise that the city’s spectacular development has resulted in “the chaos incident to rapid growth, and especially to the influx of people of many nationalities without common traditions or habits of life.” Chicago emerged so abruptly, the

Plan

explains two chapters later, that events outran its citizens’ capacity to comprehend and control them. Over the seventy-five years—a single human lifetime—in which this frontier outpost with a few dozen settlers exploded into a great metropolis encompassing close to two hundred square miles and more than two million residents, the city’s expansion was “so rapid that it has been impossible to plan for the economical disposition of the great influx of people, surging like a human tide to spread itself wherever opportunity for profitable labor offered place.” The public interest now demanded that Chicagoans lift their eyes from their limited personal concerns to those of the fundamental structure and organization of the built environment in which they all lived. A coherent and compelling strategy for creating a “well-ordered and convenient city” was now nothing short of “indispensable.”

These words, like many other passages in the

Plan of Chicago,

have inspired readers since they were published on July 4, 1909. The choice of date was noteworthy, for the

Plan

was a declaration of independence from what its framers saw as a self-imposed tyranny of unregulated development that threatened the fortunes, and perhaps even the lives and sacred honor, of the city’s residents. But was it true that Chicago had evolved without any plan?

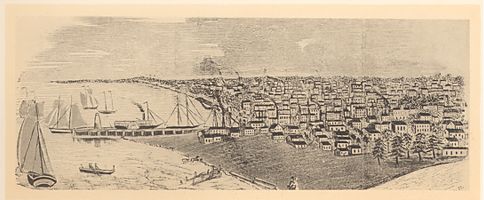

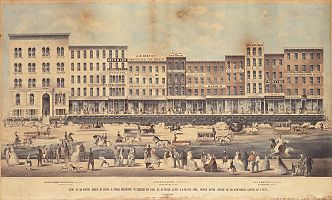

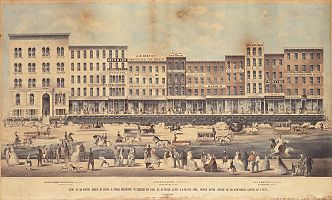

Wood-cut of Chicago in 1834

|

Motive, Means, Opportunity

In fact, by 1909 Chicago had been the site of many plans. While the city always attracted opportunists focused only on immediate gain, as early as the 1830s it was being fashioned by people who consistently looked ahead. This hardly means that they did not often pursue very short-term—and short-sighted—goals. But they consistently and actively attempted to create what was by their lights a better city, in the belief, shared by the authors of the

Plan,

that improving Chicago as a whole would benefit the individuals who lived within it.

A Splendid Location

|

The place and the times rewarded Chicagoans’ efforts to grow their own and their city’s fortunes. Modern Chicago owes its origins to its location at the southwestern edge of the

Great Lakes

near a convenient portage to the Mississippi Valley and the heart of the continent. The most distinctive feature of the setting was, paradoxically, its lack of distinctive features. The level prairie that stretched in all directions away from the lake invited the most ambitious conceptions by offering few obvious natural obstacles to their realization. The prairie and the lake, the

Plan

observes, “each immeasurable by the senses,” dictate the scale of possibility in Chicago. “Whatever man undertakes here,” it continues, “should be either actually or seemingly without limit.” While European explorers recognized the area’s promise as early as the 1670s, the fulfillment of its potential had to wait for the right historical moment. This arrived in the antebellum decades with the onset of the industrial, transportation, and communication revolutions in the United States.

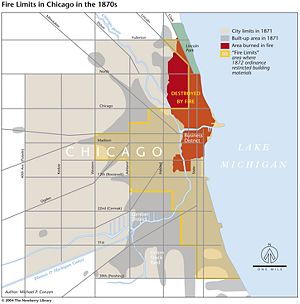

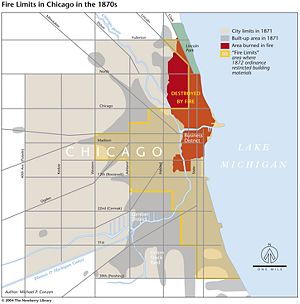

These developments animated an increasingly networked national and international free market economy, a jump in both immigration from abroad and population mobility within the nation, and an ethos of hyperbolic boosterism, the local form of the national rhetoric of manifest destiny. Chicago was home to nearly thirty thousand people by 1850 and to ten times that number only twenty years later. After the

Great Fire of 1871

incinerated close to a third of the city, including the commercial downtown and most of the North Side, Chicago was speedily rebuilt, thanks to the irrepressible spirit of local residents and an infusion of capital from investors elsewhere who knew the country needed this great central marketplace. None of this happened smoothly. Considerable tumult, whether in the form of financial busts that alternated unpredictably with the booms or social and economic tensions that all too often erupted into violence, marked the city's growth through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Planning, or Destiny?

Fire Limits in Chicago in the 1870s

|

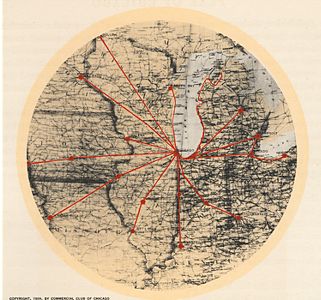

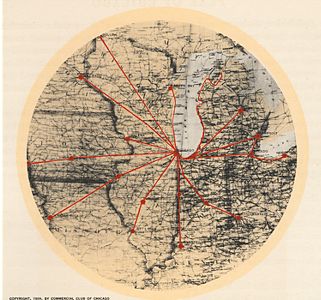

Where was planning in all this, or did the invisible hand of market forces take care of everything? In a noted address delivered in 1923 at the

Field Museum

to the Geographical Society of Chicago and appropriately titled "Chicago: A City of Destiny," J. Paul Goode, professor of geography at the

University of Chicago,

argued that the city's location, and the local population's ability to understand and exploit its advantages, made Chicago's eminence inevitable. Thirty-two years later, Harold M. Mayer, another University of Chicago geography professor speaking under the same auspices, complicated Goode's argument. Mayer began his lecture, "Chicago: City of Decisions," by citing five deliberate actions that "have carried [Chicago] toward its destiny as the Metropolis of the Midwest." These included the provision of the Federal Land Ordinance of 1785 that dictated Chicago's (and many other towns') rectangular street grid, the building of

Fort Dearborn

near the mouth of the

Chicago River

in 1803, and the choice by railroads to make Chicago what historian William Cronon has called the "gateway city" between the industrializing East and the agricultural hinterland. Of interest here is that Mayer's other two examples were the creation of the

Plan of Chicago

and "the decision to set up planning as a continuous operation in Chicago."

Constructing an Infrastructure

|

Mayer stated that he picked these five decisions "more or less arbitrarily." He claimed that he could have chosen any of a number of other examples. Among them were many of the developments that he and his coauthor Richard Wade later described in

Chicago: Growth of a Metropolis

(1969). These included the cut in the sandbar that had impeded entrance to the Chicago River and the construction of a harbor at that entrance, both accomplished by 1833; the expulsion of the

Native American

population shortly after; the greatly anticipated and much delayed completion of the

Illinois and Michigan Canal,

which was finally in operation by 1848; the raising of the city's grade and the construction of a comprehensive water works, both of which began in the 1850s; the establishment of the South, West, and Lincoln Parks and the boulevard system that connected them, starting in the late 1860s; and the successful reversal of the flow of the Chicago River, after several earlier attempts, during the 1890s. All of these entailed planning in that they were long-term coordinated efforts usually involving direct or indirect public participation, approval, and financing. Chicago was also the site of several large-scale privately funded planning initiatives, among them the opening of the

Union Stock Yard

in 1865, the building of the model town of

Pullman

in the 1880s, and the creation of the

Central Manufacturing District

in 1905. As the

Plan

said of its own purpose, the aim of all of these was "to anticipate the needs of the future as well as to provide for the necessities of the present."

In ways that transcend any individual example, the planning idea is deeply ingrained in the nature and character of Chicago. The city's lack of a long history, at least from the point of view of those not of Native American ancestry, both invited and demanded planning. One of the things that distinguished Chicago from the other leading American cities that, with the exception of New York, it surpassed in population by 1890 was the comparative brevity of its past. What history Chicago did possess its residents commonly ignored because they felt little connection to it. Through the nineteenth century, Chicago's population consisted overwhelmingly of those who, if not from somewhere else themselves, were children of parents born and raised in other places. Commonly this elsewhere was a different and distant country. And if the members of the city's commercial and social elite were largely native born, they, too, had mostly come to Chicago from other parts of the United States. Even in the early twentieth century, when the

Plan of Chicago

appeared, self-made men constituted the bulk of this elite, though more and more the sons of such economic pioneers were taking positions of leadership. For much of the city's population, moving to Chicago and allying oneself with its future had been central to their own personal plans for success. Indeed, few places were so speculatively oriented. It is no coincidence that Chicagoans created the modern commodities market, in the form of the Chicago Board of Trade, where the future itself is bought and sold. Nor was it out of the city's character that real estate developers purchased property in sparsely settled areas in anticipation of the growth that was sure to make the investment pay.

Boosters and Doubters

Nowhere else in the United States did booster rhetoric rise to such brassy grandiloquence. Of the countless speeches and tracts that boomed Chicago's prospects, few outstripped the hyperbolic optimism of the thick volume

Chicago: Past, Present, Future,

subtitled

Relations to the Great Interior, and to the Continent,

first published in 1868 by John S. Wright. Wright arrived from western Massachusetts in 1832 at the age of seventeen. Before he was twenty-one, he made a fortune in real estate speculation. Wright prepared a census and one of the earliest maps of Chicago, and he constructed at his own expense the town's first public school. Wright's real estate profits evaporated in the Panic of 1837 (he lost another fortune twenty years later investing in a new kind of reaper), but his faith in the city's prospects never wavered. Well before J. Paul Goode's address to the Geographical Society, Wright contended that the natural creation had been planned with Chicago's greatness in mind. "It is clear as sunlight," he proclaims, "that for Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, North Missouri, and part of Indiana and Michigan, this city must be the emporium." Of all America's new western cities, Wright likewise declares, Chicago "is most certain to grow." Speaking of the city's nondescript topography, Wright adds, "There never was a site more perfectly adapted by nature for a great commercial and manufacturing city, than this."

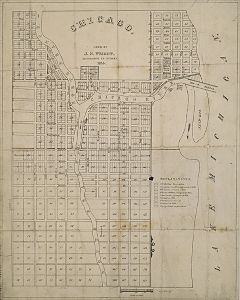

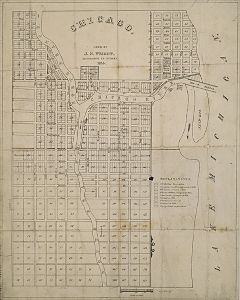

J. S. Wright, Survey Map of Chicago, 1834

|

One could dismiss all this as bombast, except for the fact that it was true. In 1861 Wright reportedly predicted that within a quarter of a century the city's population would reach one million. He was off by only four years. Wright's main point was that, whatever the momentary setbacks, Chicago's progress was irresistible. The future, the most valuable commodity in Chicago, would be bigger and better, and it would belong to those who most fully understood the potential that lay in the factors that Goode listed and who then knew how to command Chicago's promise with the kind of decisions that Mayer described. In Chicago, Mark Twain writes in

Life on the Mississippi

(1883), "they are always rubbing the lamp, and fetching up the genii, and contriving and achieving new impossibilities." For the occasional visitor, Twain explains, Chicago was always a "novelty," since "she is never the Chicago you saw when you passed through the last time."

Well before the

Plan of Chicago

was published, there were also those who anticipated its assertion that in their haste Chicagoans had built all too carelessly and with insufficient planning. Legendary landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, reflecting on the Great Chicago Fire in the

Nation

shortly after the conflagration occurred, was only one of several observers who attributed the extent of the damage to hurried and sloppy building. Olmsted—who had recently designed the South Side's

Jackson

and

Washington Parks,

as well as the elegant suburb of

Riverside

—would twenty years later be one of

Plan

author Daniel Burnham's chief collaborators on the

World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Chicago's "weakness for 'big things," its desire "to think that it was outbuilding New York," Olmsted wrote, did not directly cause but certainly invited the disaster. The editors of the

Chicago Inter-Ocean

at the time agreed, stating that the fire revealed that the city's "paramount need was harness, self-restraint, the temperance which comes from experience." None of these qualities thrived in Chicago.

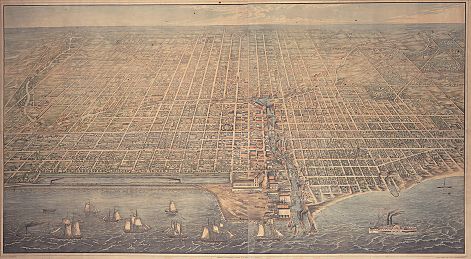

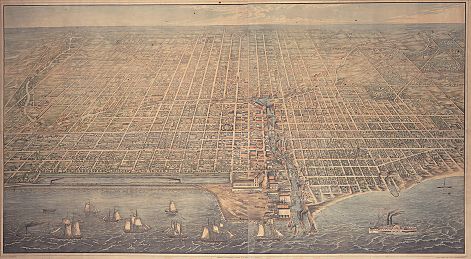

Bird's Eye View of Chicago in 1857

|

At the turn of the twentieth century, numerous observers criticized the apparent governing spirit of Chicago and other cities for thinking of planning, if at all, as mainly a matter of expanding the urban infrastructure to attract and support yet more private commercial investment. It was bad policy, these critics maintained, to entrust the future to real estate developers, project engineers, and most public officials, who rarely lifted their eyes from the matter right at hand. In too many instances, the highest concern of such people was how quickly and cheaply they could get a particular project done, not how long it would last or how it related to the city as a whole. Though by the 1880s Chicago was becoming famous for its architecture, the most skilled designers were responsible only for a limited number of buildings and did not pay a great deal of attention to the city as a whole as they worked on individual projects. Some thoughtful Chicagoans complained that their fellow citizens measured civic achievement only in quantitative rather than qualitative terms, and rarely with anything but their own personal welfare in mind. As a result, Chicago suffered from being a place where all too many people came to work and invest rather than to live, and this showed in the city they had built. In Henry Blake Fuller's novel

With the Procession

(1895), a civic-minded group aptly named the Consolation Club meets to consider the affairs of their "vast and sudden municipality." One of its members remarks sadly, "This town of ours labors under one peculiar disadvantage: it is the only great city in the world to which all its citizens have come for the one common, avowed object of making money."

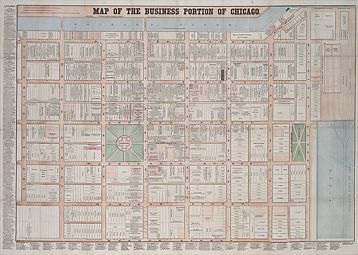

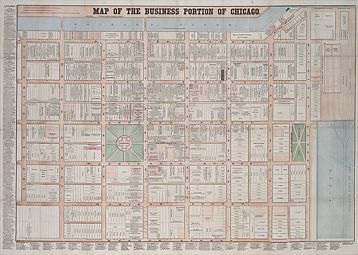

Business Section in 1862

|

The

Plan of Chicago

combines familiar booster rhetoric with the reservations expressed by Olmsted, Fuller, and others. On the one hand, it contains passages that John S. Wright could have written, as when it flatly states, "Chicago is now facing the momentous fact that fifty years hence, when the children of to-day are at the height of their power and influence, this city will be larger than London: that is, larger than any existing city." On the other hand, it rejects the idea that the city's success could or should be evaluated in terms of numbers alone, or that the future would take care of itself. While Chicago's growth had exceeded the most optimistic projections, it was time to rethink some basic conceptions of civic success. Fortunately, the

Plan

states, "the people of Chicago have ceased to be impressed by rapid growth or the great size of the city. What they insist [on] asking now is, How are we living?" The answer to that question was not reassuring, and the only proper course of action, the

Plan

asserts, was to prove Fuller's pessimism wrong and triumphantly remake the city.

|