| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

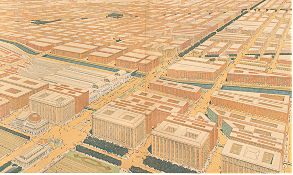

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

|

|

|

Whether Burnham would have approved of McCormick Place (1960, 1971, 1986, 1996) or the private yacht clubs currently along the lake is tougher to determine. It is possible to contend, based on his statements about the importance of protecting the lakeshore as a public resource, that he would have raised objections to them. But he himself proposed putting an exposition building and yacht clubs in Grant Park, as well as restaurants and hotels along the lagoon he wished to construct between downtown and Jackson Park. It is very likely that Burnham the fair-builder would have given his blessing to the Century of Progress Exposition of 1933-34. He probably also would have favored turning Municipal Pier into the lakefront public recreation, exhibition, and amusement area that Navy Pier is today. An avid traveler and a believer in serving the convenience of wealthy businessmen, he might well have been pleased by the opening of the Meigs Field commuter airport on Northerly Island, and he certainly would have backed the building of Midway and O'Hare airports. As a champion of the City Beautiful, he would have supported the attention Chicago has devoted in recent years to improving its appearance by planting flowers and trees and by installing neighborhood decorative markers. And while he might not have favored the postmodern architectural style of some of Millennium Park's installations, Burnham would probably have appreciated how successfully the park draws local residents and tourists to the downtown lakefront.

Part of the CityscapeAny discussion of the heritage of the Plan of Chicago and Daniel Burnham is further complicated by the iconic status both the Plan and Burnham have attained over the years. The Plan long ago ceased to be a collection of proposals and Burnham a mere architect and urban planner. They have become landmarks in the cityscape, as palpable a presence for any planner or civic leader as Michigan Avenue or Grant Park. Developers, public officials, politicians, journalists, and commentators often cite the Plan and Burnham not as part of a close analysis of the former's recommendations or of the latter's career in themselves, but in order to make their own point about Chicago or the proper direction of modern city life. Boosters of any number of different projects have invoked the famous exhortation "Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood," attributed to Burnham by Charles Moore, as if to suggest that to reject what they are proposing is an abandonment of the defining essence of Chicago's character. Others, meanwhile, blame the "big is beautiful" view that these words convey for making the city, in their opinion at least, inimical to small-scale human needs.

|

Twentieth-century historian and cultural critic Lewis Mumford is among those who attacked the Plan for this reason. In the tradition of Louis Sullivan, who characterized Burnham as "a colossal merchandiser," Mumford criticized Burnham for being primarily interested in pumping up land values, a charge that has also been leveled at the Commercial Club, whose financial and emotional investments in Chicago mutually reinforced one another. In The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects (1961), Mumford calls the Plan the fullest example of twentieth-century "baroque planning," a set of ideas with "no concern for the neighborhood as an integral unit, no regard for family housing, no sufficient conception of the ordering of business and industry themselves as a necessary part of any larger achievement of urban order."

Mumford observes, however, that despite the "ruthless overriding of historical realities" implicit in the famous quotation about making no little plans, "there was a measure of deep human insight" in it as well. Burnham's planning vision, whether sound or misguided, does in fact stir the blood because it so powerfully expresses the desire to be able to reach beyond piecemeal solutions and act efficaciously on the grandest scale. At the very moment when life became modern and Americans realized that twentieth-century urban experience was fraught with limitations and contingencies, Burnham insisted that if we are just bold and brave and determined enough, it is possible to master time and space and make all things right. The Plan's very real historical appeal lies precisely in the fact that it proclaims history is no match for human will, and cities can determine rather than merely accept their fate. The question remains whether the thinking behind this proclamation is correct or misguided, sound policy for the future or the last gasp of wishful thinking by the spokesman for a passing age.

The Decline of Comprehensive Planning

|

Abbott's description of the narrowing focus of urban plans is accurate. Public or semi-public agencies and neighborhood or private groups have prepared dozens of planning studies and documents that deal with defined parts of the built environment of Chicago or that aim to improve a specific aspect of city life. As early as 1913, the City Club of Chicago sponsored a competition to encourage better planning of the outskirts of the city, with the goal of creating attractive and functional residential areas. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, proposals focused separately on parks and parkways, a new subway system, and water and sewerage facilities. In the following decade, planners concentrated on reviving the city's industrial base and making older areas of Chicago more appealing places to live. This was a response to the aging of the city's infrastructure, factories, and housing stock, in part because of deferred maintenance due to the Depression and the Second World War.

In 1909 the planners were concerned with how to continue attracting people to Chicago. Following World War II, the issue was how to get them to stay. After peaking in the early 1950s, Chicago's population began to decline. Meanwhile, the percentage of African Americans rapidly rose from 8.2 percent in 1940 to 13.6 percent a decade later. As a result, a not very hidden question in some proposals was how to maintain a sense of community in a city sharply divided by race, which, many argued, was an important factor in the migration of white Chicagoans to the suburbs. In July 1943, before the significant population boom of towns surrounding the city, the Chicago Plan Commission issued a report titled Building New Neighborhoods, stating that its purpose was to make suburban-style residences in the city that would keep Chicagoans in Chicago.

The previous year the commission had published Forty-four Cities in the City of Chicago, which highlighted what made individual neighborhoods in the city so special. In 1946 it collaborated with the Woodlawn Planning Committee to use that South Side neighborhood as an example of how to analyze the problems facing "middle-aged" Chicago residential areas. The purpose of this study was to find a way to revitalize communities through better use of land, reconstruction of physical facilities, and improved services. In 1951 the commission released a report on industry proposing zoning changes and other measures to redevelop blighted homes and factories and to cluster the latter more efficiently. Five years later a group at the University of Chicago working for the city's Community Conservation Board analyzed how the Hyde Park - Kenwood neighborhood might be made more orderly and stable by clearing slums, constructing better housing, and considering what other steps might contribute to a viable community.

The Focus on the Central Area

|

|

As its name indicates, the Development Plan for the Central Area, ambitious as it was, covered only the part of the city discussed in the Plan of Chicago's chapter "The Heart of Chicago." The 1972 Lakefront Plan of Chicago likewise focused just on the area specified in its title, while the Chicago 21 plan of 1973 was an updating of the 1958 Development Plan for the Central Area. The Lakefront Plan aimed at consolidating public control of the lakefront, maintaining and enhancing the lakeshore parks and water quality, and ensuring that Lake Shore Drive retained the qualities of a scenic parkway. Chicago 21 confronted what it saw as the continuing deterioration of the central city, especially for purposes other than work. While its State Street Mall proposal was a notable failure as an attempt to compete with outlying shopping centers, the construction of the Harold Washington Library Center (1991), improvements in transportation, the location of some city colleges and private university facilities in or near the Loop, and the recent residential boom throughout the central area demonstrate the considerable influence of Chicago 21 proposals.

The latest iteration of a city-sponsored plan for the downtown is the Central Area Plan of 2003, which was prepared by the departments of Planning and Development, Transportation, and Environment of the administration of Mayor Richard M. Daley. Predicting that by 2020 there will be more jobs, residents, tourists, students, and retail establishments in the Central Area, this document calls for some of the same things the Plan of Chicago discussed a century ago, notably better public transportation facilities and further development of the waterfront for public use. But it speaks more to current concerns than those of 1909 when it discusses the need for Chicago to be a sustainable city that respects and preserves its past.

Even if none of these plans are as all-encompassing as the Plan of Chicago, several of them claimed to be part of its heritage. In his foreword to the Chicago 21 plan, Mayor Richard J. Daley notes the inspiration of "Burnham's dream" that "gave great emphasis to the central area." The 1949 proposal for a civic center contended that it was in the spirit of the Plan even if it rejected the Plan's neoclassical aesthetics. It argued for new government buildings that would be state-of-the-art high-rises (as the Daley Center turned out to be) quite different from the Plan's domed colossus. Chicago 21 asserts that "the present generation, while enjoying the fruits of the Burnham Plan, can also contribute to the heritage of future generations" with a "soundly conceived" civic center that is "conveniently located" and "appropriately designed."

Back to the Big PicturePlans continued to appear that were as broad in scope as the Plan of Chicago, though they differed from the Plan at least as much as they resembled it. The Chicago Plan Commission's 1966 Comprehensive Plan of Chicago discussed the city as a whole, but it emphasized a quality-of-life agenda much more than Burnham and the Commercial Club had done. It discussed the need to improve living conditions for families, working people, and the disadvantaged. Issued shortly before the urban riots of the late 1960s and at a time when Chicago's era as an industrial giant was nearing its end, the Comprehensive Plan was concerned with countering residential segregation and creating more service-economy jobs, as well as improving housing, transportation, recreational facilities, and public education. As Carl Abbott points out, however, devising effective ways to improve society has been a harder task for planners than implementing physical changes. Finding good housing for poor and middle-class residents, countering racial segregation, and maintaining a high-quality school system that successfully serves all of its students have proved to be elusive goals.

Two proposals stand out as direct heirs to the Plan of Chicago, and both have sound claims to the pedigree. One of the two authors of the Chicago Regional Planning Association's 1956 Planning the Region of Chicago was none other than architect Daniel H. Burnham, Jr., who for thirty years had been president of the Association. Burnham's coauthor was Robert Kingery (after whom the Kingery Expressway is named), the association's general manager and former director of the Illinois Department of Public Works. Planning the Region of Chicago is dedicated to the Merchants Club of Chicago, whose members, the lengthy dedication informs us, "have maintained their interest and have continued to direct the carrying out of the Plan of Chicago and, more recently, of Regional Planning in the Region of Chicago." The dedication continues, "In the twilight of their lives, the few and far-scattered survivors of the Merchants Club arranged for publication of this book." They did so "not merely as a record of outstanding accomplishments," but also "as a challenge to the young men of today to grasp and cherish the torch their forefathers kindled." Planning the Region of Chicago, while not as luxuriously presented as the Plan of Chicago, otherwise closely resembles it in size, layout, and topics covered, though, as its title implies, it discusses Chicago in relation to its region more than does the Plan.

|

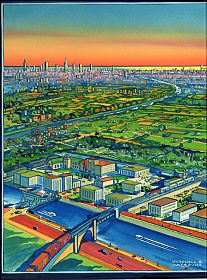

A more recent proposal that explicitly recalls the Plan of Chicago is Chicago Metropolis 2020, subtitled The Chicago Plan for the Twenty-first Century, which was published in 2001. Like the Plan of Chicago, Chicago Metropolis 2020 was sponsored by the Commercial Club, along with the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Its informative maps and charts and its striking photography also recall the Plan, as does its cover, which is an updated Jules Guerin bird's-eye-view rendering of downtown Chicago as seen from the lake. Its author is Chicago attorney Elmer W. Johnson, former president of the Aspen Institute and member of both sponsoring organizations. Chicago Metropolis 2020 takes as its starting point some of the premises of the Plan of Chicago, most notably that Chicago is a commercial city that must plan ahead very carefully and find sensible solutions if it is to thrive. Like the Plan and Planning the Region of Chicago, Chicago Metropolis 2020 talks about the necessity of thinking regionally, pointing out that the region of Chicago now includes Cook and all of the five contiguous counties.

Chicago Metropolis 2020 discusses many of the same kinds of topics as the Plan of Chicago and Planning the Region of Chicago, notably economic vitality, transportation, recreation, and land use. Harking back to the Progressive program of a century earlier, it also recommends streamlining governing agencies. Like the Plan, it discusses the legislation required to bring about change and the need to educate the public on the virtues of planning. But its approach is quite different from the Plan in some important ways. Basing its analysis on recent historical and social science scholarship, Chicago Metropolis 2020 puts much more emphasis on the issues of better schools, expanded health and child care, and improved services for low-income families.

Since producing its book, the Chicago Metropolis 2020 organization has evolved into a group that recalls the Chicago Plan Commission. Like the commission, it sends its leaders and staff to speak with public officials and civic organizations, and it continues to publish promotional literature. But its spokespersons use PowerPoint rather than lantern slides to make their presentations, and some of its publications either appear on the Web or come with a CD-ROM. Following the example of Wacker's Manual, Chicago Metropolis 2020 aims to capture the interest of younger people, though its means is not a civics textbook with review questions but a Web-based computer game that features a street-smart character named Metro Joe.

In some ways, then, planning for the future of Chicago has come full circle in the century that has passed since the publication of the Plan of Chicago, but in other ways it has changed considerably. Chicago Metropolis 2020 is based on the idea that public and private interests can and must league together to remake a metropolitan community for the benefit of everyone. It believes, as did the Plan, that idealistic and practical goals are not at odds with each other. It is similarly concerned with sustaining Chicago's growth by disciplining it. And the "make no little plans" philosophy informs both documents. But there is a fuller recognition now that the planning effort requires facing more complex human issues than can be solved by building more parks, enforcing sanitary measures, and other design and engineering solutions that do not take fully into account the social as well as physical structure of the metropolis.

The idea of comprehensive community planning faces stiff resistance from the cherished idea that people should be able to do with their lives and their property as they wish. There are many more politically empowered interest groups now than there were in 1909 who want their needs to be met and their desires to be fulfilled. This is a good thing for a truly democratic society, but it makes it hard to find or build a consensus in support of a comprehensive regional plan for a place as large and diverse as metropolitan Chicago. What keeps the planning idea alive and well in Chicago and other cities is a continuing faith in both city life and in the belief that it should, can, and must constantly be remade for the better.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.