| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

|

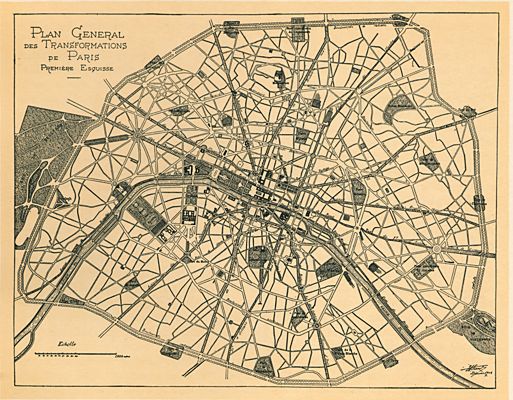

The Plan praises Napoleon Bonaparte for extending the planning tradition in Paris, but its real hero is Georges Eugéne Haussmann, Napoleon III's prefect of the Seine. Beginning in the 1850s, Haussmann undertook, as the Plan wished to do in Chicago, "the great work of breaking through the old city, of opening it to light and air, and of making it fit to sustain the army of merchants and manufacturers which makes Paris to-day the center of a commerce as wide as civilization itself." The Plan characterizes Haussmann as Daniel Burnham, its principal author, wished to see himself in regard to Chicago: as a practical urban visionary of unimpeachable taste, integrity, determination, and genius. "As if by intuition," the Plan says of Haussmann, "he grasped the entire problem. Taking counsel neither of expediency nor of compromise, he ever sought the true and proper solution. To him Paris appeared as a highly organized unit, and he strove to create ideal conditions throughout the city."

|

The Plan then surveys what it sees as other instances of sound planning in contemporary Europe. It praises several cities, though it singles out London as a noteworthy negative example for squandering numerous opportunities to improve its built environment, beginning with its failure to entrust its future to a brilliant architect after the Great Fire of 1666 when it did not adopt Sir Christopher Wren's rebuilding plan. Turning then to the United States, the Plan applauds President George Washington's wisdom in appointing the French-born engineer and architect Pierre-Charles L'Enfant to design the new national capital named after the first president, and it praises L'Enfant's plan itself for creating a dignified seat of American government. The Plan admires, for example, how L'Enfant's multiple diagonal avenues cut through a basic rectilinear grid, masterfully creating dramatic focal points for public buildings.

As useful as it may be to understand the Plan of Chicago as part of a long heritage of planning, it is perhaps more revealing to try to see it in terms of its own particular time and place, as a contribution to a continuing discussion of what turn-of-the-century urban America was and might be. Chicago and other cities faced the compelling question of whether the often unsightly and unsanitary modern commercial and industrial metropolis should and could be transformed for the better through concerted and enlightened action. The period witnessed the creation of hundreds of local and national civic associations that claimed to be dedicated to improving urban life by making it more attractive, healthy, and efficient.

|

For example, the authorization by the Illinois legislature in 1889 of the Sanitary Commission for the purpose of reversing the flow of the Chicago River reflected the idea—which was an article of faith in the Plan of Chicago —that it was essential to think regionally and not locally in dealing with urban infrastructure. The exposé of the horrific housing conditions among the immigrant poor and the call for tenement reform legislation in Jacob Riis's How the Other Half Lives (1890), though this book focused on New York, advanced a sympathetic understanding nationally that the sources of much antisocial behavior lay in the terrible conditions in which people were forced to live. For many middle- and upper-class Americans committed to improving city life, the key to effective action was enacting the Progressive agenda of reform and regulation—including reform of government and regulation of large business interests—entrusted to supposedly objective professionals.

|

The first major program of Progressive city planning was the so-called City Beautiful movement, in which Daniel Burnham was the central figure. Its proponents called for transforming the urban environment, as Haussmann had done in Paris, into what they believed was a more beautiful, unified, and efficient arrangement of its parts, all interconnected with handsomely landscaped streets and boulevards. Gracing this noble cityscape would be great public architecture, preferably in the neoclassical style, including if at all possible an imposing civic center. Such a setting would also inspire a sense of community among a city's heterogeneous population. This would in turn reduce conflict while increasing economic productivity.

City Beautiful advocates were well aware that American cities could not be mere showplaces since these urban centers were, above all, commercial entities created to serve the needs of industrial capitalism. They believed not only that it was possible for a city to be both attractive and efficient, but also that a beautiful city would function more effectively than an unappealing one. The movement did not directly address perceived social ills and inequities as such, but placed great faith in the harmonizing powers of municipal art, expressed in magnificent parks, buildings, boulevards, and public gathering places adorned with fountains and statuary. While many of those who articulated and supported City Beautiful ideas were sincere in their belief that their goal was to improve urban life, they are justifiably open to the charge that theirs was an elitist top-down approach that expressed self-interested anxieties about urban democracy and a desire to impose their own vision of an orderly metropolis on immigrants and workers in the hope of asserting social control.

Other Urban Alternatives

In urban America generally and in Chicago particularly, other initiatives at this time attempted to address the problematic aspects of America's metropolitan future. Several of these efforts revealed the urgency with which their advocates believed that proactive measures were required. One "solution" to the "problem" of the city was to start over and build an entirely new urban community, sometimes in convenient proximity to the old, as George Pullman did in constructing Pullman in the early 1880s in Hyde Park, which was then just outside Chicago's city limits.

|

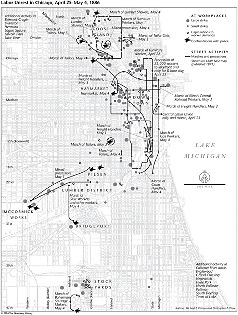

Other social commentators and activists, alarmed by what they saw as the inherently dysfunctional nature of urban life, suggested more radical measures within the existing city. The Haymarket bombing, which took place at a labor protest rally only a few blocks from downtown Chicago, was one of the distressing events that prompted Edward Bellamy to write his novel Looking Backward (1888). Bellamy's description of a utopian Boston in 2000 anticipates the City Beautiful movement and the Plan. The immense popularity of this book reveals that Bellamy spoke to a widely felt concern. His reconstructed Boston consists of "miles of broad streets" that are "shaded by trees and lined with fine buildings." Every section of the city features "large open squares filled with trees, among which statues glistened and fountains flashed in the late afternoon sun." Public buildings of "colossal size" and "architectural grandeur" delight the eye.

Some Chicagoans took more direct steps to engage with the problems of urban life. In September 1889 Jane Addams began her life's work in the social settlement of Hull House on the Near West Side. By the time the Plan of Chicago was published, the settlement had blossomed into a complex of thirteen buildings that hosted dozens of activities aimed at addressing Addams's belief, also voiced by Bellamy, that "the social organism has broken down through large districts of our great cities."

|

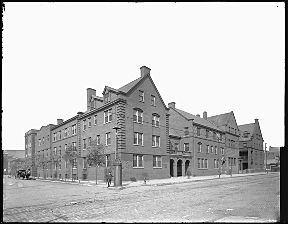

Chicagoans who looked to force rather than understanding as the "solution" to the "problem" of the modern city constructed urban institutions very different from Hull House. A few years before the settlement opened, members of the Commercial Club, which would later commission Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett to prepare the Plan of Chicago, successfully lobbied the federal government for a permanent garrison of federal troops to guard Chicago—and them—from "internal insurrection," a euphemism for labor and class uprisings. To facilitate this effort, they donated the land for what became Fort Sheridan, located about thirty miles north of the city. Chicago was also a participant in the movement to build within American cities what were essentially fortresses for local military units. The firm of Burnham and his partner John Wellborn Root was hired in the late 1880s to design the imposing First Regiment Armory, strategically located at Michigan Avenue and Sixteenth Street, between the city center and the posh Prairie Avenue neighborhood where several Commercial Club members lived.

Enter Daniel Burnham

|

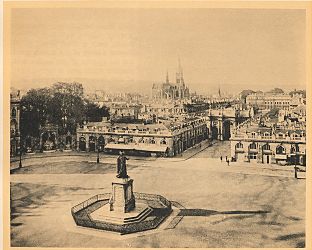

The Columbian Exposition as a whole, and especially the vast and statue-studded exhibition halls assembled around the grand basin in the fair's Court of Honor, was a cultural milestone that established City Beautiful principles as the standard for contemporary urban design. The central principle was the careful coordination of different elements with an eye to both efficiency and aesthetic appeal. Frederick Law Olmsted's ground plan emphasized functionality as well as visual pleasure, anticipating likely pedestrian flow patterns and integrating several modes of transportation. The fair builders devoted almost as much attention to plumbing and garbage removal as they did to monumental display. Even as it championed Beaux-Arts time-honored neoclassicism as the architectural vocabulary of the City Beautiful, the exposition embraced the most modern technologies, notably electric lighting that dazzled evening visitors to the Court of Honor.

Other Cities, Other Plans

|

Almost immediately after the Washington work, Burnham was appointed by the governor of Ohio to lead a three-man team that prepared a plan to revitalize Cleveland's blighted lakefront. This plan recommended the coordinated construction of a group of large government buildings and a central railway station. The Cleveland plan of 1903 was followed the next year by a plan for San Francisco. Burnham's trusted assistant on this job was his new employee and future coauthor of the Plan of Chicago, thirty-year-old Edward Bennett, with whom he had first worked on an unsuccessful entry in a competition to redesign the United States Military Academy at West Point.

|

In spite of the fact that much of downtown San Francisco was destroyed by the earthquake and fire of 1906 shortly after Burnham and Bennett submitted their proposals, their ideas had little direct influence beyond the rebuilt city's Civic Center. Following the earthquake, many property owners, businessmen, and politicians were more eager to restore the basic layout of the pre-disaster city than to build something that seemed radically new and not immediately practical. In any event, advocates of Burnham's plan for San Francisco could not generate wide public support for its implementation. Burnham left Bennett in charge of the San Francisco project for yet another planning commission. This time the client was the federal government, which wanted Burnham to redesign Manila and the summer administrative capital of Baguio in the Philippines, which the United States had recently acquired in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars.

Remaking Chicago

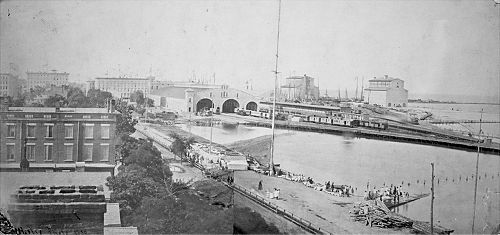

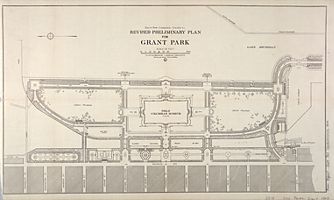

While all this work in other cities was essential to Daniel Burnham's continuing development as a planner, more directly pertinent to the Plan of Chicago were the proposals he presented in the years following the Columbian Exposition for reconfiguring Chicago's lakefront. Burnham's much-lauded triumph with the fair inspired him to design a continuous landscaped connection between the former exposition site in Jackson Park and a reconceived Grant Park (called Lake Park until 1901), the area located east of the city's center and framed by Randolph Street, Michigan Avenue, Twelfth Street (now Roosevelt Road), and the lake. Burnham was neither the only nor even the first person to suggest how the downtown lakefront might be improved. Mail-order magnate A. Montgomery Ward waged a twenty-year battle, not finally resolved until 1911, to assure that the park would "remain public ground forever open, clear and free of any buildings, or other obstruction whatever," as stated on the map drawn up by the first Illinois and Michigan Canal commissioners in 1836.

For decades the chief impediment to taking full advantage of the park's location was an 1852 ordinance granting the Illinois Central Railroad the rights to a 300-foot-wide strip of land (then submerged by the lake) between Twenty-second and Randolph Streets, on which the Illinois Central erected a trestle and tracks, in the process creating a breakwater that protected the shoreline from erosion. The purpose of this measure was to spare the city the expense of constructing the breakwater. The Illinois Central not only built the trestle, but also purchased from the federal government former Fort Dearborn land north of Randolph Street, where the company situated a passenger station and facilities for its rolling stock. (Former Illinois Central property between Randolph and Monroe Streets has recently been converted into Millennium Park, which opened in 2004.)

|

Nineteenth-century maps and drawings reveal that much of the current parkland between the Illinois Central tracks and Michigan Avenue, as well as east of the tracks, was originally under water. It was filled in by 1890, a good deal of it shortly after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 with rubble from the burned-out city. The lakefront was an unsightly mess, however, littered with stables, squatters' shacks, a firehouse, garbage, and general debris, along with railroad tracks and service buildings. Beyond this disarray, so near and yet so far, lay the glittering lake. The city had its own hopes of redeveloping Lake Park with municipal buildings, including a new city hall. The determined Ward, at a great cost to his wallet and popularity, won a series of lawsuits to remove current structures and prevent the erection of new ones, whether private or public. The notable exception was the Art Institute, but Ward was ultimately victorious in keeping out other proposed improvements, including an armory, a parade ground, and the Field Museum. This last institution, then called the Field Columbian Museum, was funded by Marshall Field in the wake of the Columbian Exposition and temporarily housed in the fair's Fine Arts Building, which was later substantially rebuilt as the home of the Museum of Science and Industry (1933). The new Field Museum opened in 1921 at its current site, just south of Grant Park on filled land donated by the Illinois Central.

|

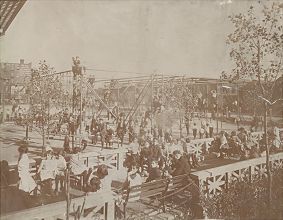

The legal dispute over the lakefront took place in the context of a nationwide urban park and playground movement that viewed recreational space in more active terms than previously, as a place for physical exercise as well as the appreciation of nature. Reformers stressed that convenient access to parks and playgrounds was especially important for workers and their children, who endured imaginatively and physically restricted lives in the grim and endless grid. A Special Park Commission chaired by the brilliant architect Dwight H. Perkins submitted a much-cited report in 1904 that bemoaned Chicago's decline between 1870 and 1900 from second to thirty-second place among large cities in the amount of park acreage per resident. It heartened the commission to discover that, thanks to the contributions of private citizens and public appropriations, the number of playgrounds in Chicago had increased from five to nine over the past four years. The commission would continue to praise such progress in its subsequent reports. Among the organizations advocating more recreational opportunities for working Chicagoans and their families was Hull House, which built one of the first playgrounds in the city, as well as various businessmen's groups. Olmsted's sons and Burnham's architectural firm were hired to design several new parks and fieldhouses.

|

A Comprehensive Plan Emerges

Daniel Burnham's ideas for the lakefront reflected his belief, based on his experience with the fair, in the value of thinking big. Working with his associate Charles B. Atwood, who had been responsible for the Fine Arts Building and numerous other structures at the fair, Burnham combined a new design for Lake Park with a plan to link it to Jackson Park. Encouraging Burnham was businessman James W. Ellsworth, who had been on the fair's Board of Directors. Ellsworth was currently head of the South Park Commission, whose authority included Jackson Park and, by 1901, the newly named Grant Park. During the spring of 1896, Burnham shared some of his ideas with Ellsworth and his fellow commissioners. In July he invited Ellsworth, several commissioners, Mayor Swift, and others to his office for a formal presentation. This was followed by more meetings and then an after-dinner speech on October 10 in Ellsworth's home. This occasion was attended by such luminaries as Marshall Field and George Pullman, and it was reported on the front page of the Chicago Tribune the next day.

On October 12 the paper published an editorial praising the scale of Burnham's proposals, the "taste and skill" of their conception, and the "eloquent manner" with which he advanced them. The Tribune also commended Burnham's "public spirit and undaunted faith in the future of Chicago." Like the fair, the Tribune said, this new plan demonstrated Burnham's "originality, daring, and genius," which were so aptly representative of Chicago, though the editorial ended on a more cautious note in advising that "this grand scheme involves so much work, thought, money, and originality that it should not be entered upon with haste." The city council soon passed an ordinance entrusting the lakefront and improvements to the South Park commissioners, but Ellsworth stated that nothing could be done until the state legislature authorized funding. Burnham continued to press his plan in talks before other civic organizations, among these the Commercial Club and the Merchants Club.

|

Burnham's design for Lake Park was a more elegant and elaborate variation on the one submitted by the Municipal Improvement League. It revealed that he believed in keeping the lakefront open and free, but not necessarily clear. Burnham dispensed with the two basins, and he shifted the park's main east-west axis a block north to Congress Street, which would extend eastward over the Illinois Central tracks and terminate in a plaza in front of the new Field Museum. Between the museum and a yacht harbor in the lake would be a great fountain. North of the Field Museum Burnham placed, as the Municipal Improvement League had also proposed, a parade ground and an armory, south of it a playground and an exposition building. One of the boldest features of Burnham's scheme was a marble-clad tunnel connecting the North and South Side lakefronts. The tunnel would begin a block north of the Art Institute, proceed under the Chicago River, and emerge on Pine Street (later North Michigan Avenue), which in turn would lead northward to Lincoln Park and, beyond that, to Evanston.

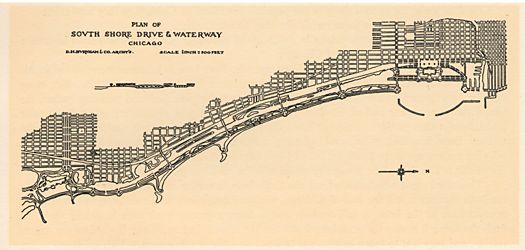

Burnham's grandest recommendation, however, was to create new green space along the lake between Lake Park and Jackson Park. For the entire six-mile stretch, he stated, the city should construct new land with fill and sculpt along its eastern edge a continuous lagoon, dotted with numerous small islands and navigable by small pleasure boats. On the lake side of the lagoon would be a glorious landscaped parkway with separate paths for carriages, horseback riders, bicyclists, and pedestrians. The parkway would be conveniently linked to the mainland with numerous bridges. Everything would be arranged to offer the most advantageous views of the lake, the city, and the park itself. As for the cost, the park commissioners might produce revenue by renting land beside the new South Shore Drive to clubs, hotels, and residences.

|

Many of these ideas later found their way into the Plan of Chicago, but Burnham's approach to the lakefront looked ahead in other ways. His correspondence reveals that he understood the importance of attracting and shaping public opinion. He alternately cajoled reporters into keeping quiet about work in progress and made certain that they would attend and tell their readers about important presentations. Similarly, Burnham took care to see that potential skeptics and opponents, as well as local supporters, were invited to the presentations. He also identified the legal issues that needed attention. He used lantern slides and artists' renderings (Burnham himself executed a water color of the shoreline parkway) to captivate audiences, as he would in promoting the Plan. The meticulous attention Burnham paid to even small details and his willingness to speak to multiple audiences over an extended period demonstrated both his dedication and his stamina. His promotional efforts also underscored his profound love for Chicago and his ambitions for it. He charged no fee, though his proposals and the publicity they generated were doubtless good for his architectural firm.

Burnham's speeches on his park proposals predicted some passages from the Plan. While he adapted these speeches to suit different audiences, they contained many similar elements, including repeated references to the lofty standard set by Pericles and Haussmann. Like all City Beautiful rhetoric, they claimed to emphasize the practical as well as the ideal—that is, the benefits planning brought to real estate values as well as to the city's civic well-being. Burnham repeatedly predicted that if Chicago became more beautiful, its wealthy residents would spend more of their money in their home city since they would no longer feel compelled to travel elsewhere to satisfy their desire to be in aesthetically attractive places. He appealed to his listeners' faith in the greatness of Chicago and their pride of leadership, at the same time warning them that unless they acted immediately, their city would suffer and would fall behind in its competition with other urban centers. If they were concerned about costs, they should be aware that delay promised only greater expense at a later date.

|

That Burnham was sincere in all these beliefs is evident from his private correspondence. In February 1897 he shared his thoughts on the progress of his lakefront plans with his father-in-law and confidant John B. Sherman, "I am for the improvement, heart and soul. I want no money nor place, but see clearly that the best welfare of the City demands that the town should immediately put on a charming dress and thus stop our people from running away, and bring rich people here, rather than have them go elsewhere to spend their money." While Burnham frequently spoke of the importance of the lakefront for the less fortunate as well as the rich, he believed in a trickle-down approach. In one 1896 talk, for example, he observed, "The more the rich spend the better for the poor."

Many passages in Burnham's speeches also expressed his visionary qualities, based on his Swedenborgian religious ideals and belief that there was a positive spirit suffusing the Creation. One of his many great gifts was his ability to move his listeners to share his view of the higher purposes of proper planning. Burnham's inspirational abilities are evident in the Plan of Chicago. For example, the Plan evokes a sense of wonder when it speaks of the importance of the lake as Chicago's leading natural asset and the need for the city to take far greater advantage of its splendid presence. The lake's vast serenity, we read, induces "calm thoughts and feelings" and provides "escape from the petty things of life." It is "a living thing, delighting man's eye and refreshing his spirit." More than a decade earlier, Burnham ended some of his speeches with a similar invitation to appreciate this resource that lay waiting right at hand for all Chicagoans. "It seems," he reflected, "as if the lake has been singing to us all these years until we have become responsive and now we see the broad water ruffled by the gentle breeze upon its breast." After describing to his rapt listeners the magnificent cityscape his proposals would make possible, this most urban of men concluded, "We are merged into nature and become part of her."

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.