| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

|

In every respect the Plan ’s defining qualities bear the signature of the two main forces behind it, Daniel Burnham and the Commercial Club of Chicago. For Burnham, the Plan was the last and in some respects the greatest achievement in his extraordinary professional career. It reflects his remarkable combination of breadth of vision and grasp of salient detail, his ability to maintain a single-minded sense of purpose while juggling multiple daunting tasks, his commanding management style, and his intuitive sense of how to appeal to his clients’ best sense of themselves. For the Commercial Club, remaking Chicago was the kind of project that resonated profoundly in its members’ imaginations and made the fullest use of the knowledge and skills that had won them high positions among the city’s business leaders and election to this exclusive organization.

The Making of a City Maker

|

|

Young Daniel Burnham was very uncertain about his future, but he appears to have discovered his calling in the fall of 1867 as a draftsman in the firm of architect William Le Baron Jenney. Thrilled by Jenney's praise, Burnham wrote with pride and excitement to his mother, “I am perfectly in love with my profession,” adding, “And for the first time in my life I feel perfectly certain that I have found my vocation.” The following spring Burnham told her that he was resolved “to become the greatest architect in the city or country.” In his correspondence with his mother, he also reaffirmed his belief—rooted in his upbringing in the Swedenborgian New Jerusalem Church—in the individual’s free-willed ability to work for good. A typical business career, Burnham confided, was full of moral pitfalls. “But there can be none in a man’s striving after the beautiful and useful laws God has created to govern his material universe," he wrote, "and when I am trying to find them and apply them to use among my fellows He will reveal them and expand my mind and heart toward himself and all mankind.” This outlook shaped his entire professional and public life.

As sure as he seemed to have been about the merits of his job, Burnham nevertheless left the drafting table in 1869 to try his luck at mining in Nevada, which had been admitted to the Union only five years before, and in his brief residence in the West he even made a failed run for the state senate. This diversion from his recent decision to become an architect may reflect less an inconstancy of purpose than it does a common pattern of the times, when many young men dabbled in often very different careers in scattered places before settling down. Both Pullman and Chicago meatpacker Philip D. Armour, for example, had similar experiences in the West. Once back in Chicago, Burnham resumed his architectural work. In the firm of Carter, Drake and Wight, he met another young, talented, and ambitious employee, John Wellborn Root. By 1873, the year Burnham turned twenty-seven and Root twenty-three, the two men had formed their own partnership.

Burnham the Architect

|

This work began with the ten-story Montauk Block (1882) at Monroe and Dearborn Streets, often called the first skyscraper, and several structures that still grace Chicago. These include the Rookery Building (1888) at LaSalle and Adams, where Burnham and Root located their firm, and the Monadnock Building (1891) at Jackson and Dearborn. They did work in other cities, but Chicagoans remained their main clients. Burnham and Root’s commissions included park buildings, railroad terminals, banks, and hotels, not to mention the original home of the Art Institute of Chicago (1887) at Michigan and Van Buren. Their Rand-McNally Building (1890), on Adams Street between LaSalle and Quincy, was the first all steel-frame skyscraper.

|

While Root was the primary designer, Burnham determined many of the important general specifications in the plans the firm produced. He also furnished the organizational, administrative, and promotional skills crucial to finding and satisfying clients, coordinating responsibilities within the office, and executing buildings of quality and distinction. In 1886 Burnham, now a prosperous man, moved his family—he and Margaret had two daughters and three sons—to a sixteen-room house on a six-acre wooded plot by the lakefront in Evanston. This champion of city life explained in another letter to his mother, “I did it because I can no longer bear to have my children run in the streets of Chicago, and because especially I can not stand them being on the South Side.” Burnham and Root’s highly successful and harmonious partnership came to a premature end with Root’s death at forty-one in 1891, during preliminary planning for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Burnham reorganized the firm into D. H. Burnham and Company, which received more than two hundred commissions, most of them for large structures, by the time of Burnham’s own passing in 1912.

|

Among major D. H. Burnham and Company buildings still extant are the Reliance Building (1895, original plan by Root in 1891—now the Hotel Burnham) at the southwest corner Washington and State Streets, portions of the Marshall Field and Company Store (1892, with several subsequent additions) diagonally across the street, and Orchestra Hall (1905) on Michigan Avenue south of Adams Street. The firm designed the Railway Exchange Building (1904, now the Santa Fe Building), just south of Orchestra Hall, and moved its offices there. Notable D. H. Burnham and Company buildings outside of Chicago include the Flatiron Building (1902) in New York, Union Station (1907) in Washington, D.C., and the John Wanamaker store in Philadelphia—the sumptuous retail palace whose 1909 grand opening was attended by President William Howard Taft.

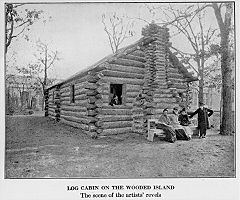

From Architect to PlannerBurnham’s engagement in the kind of projects that led to the Plan of Chicago began with his supervision of the design and construction of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. However one assesses the fair, it is impossible not to be impressed by Burnham’s almost superhuman drive and managerial ability on this colossal project. He moved into a cabin on the site in Jackson Park, from which he directed the activities of dozens of artisans and hundreds of workers. His dedication and determination were so prodigious that it seems almost as if he lifted the immense buildings from the mud and slush by an act of personal will. As the May 1 opening date approached, he wrote to his wife Margaret, “The intensity of this last month is very great indeed. You can little imagine it. I am surprised at my own calmness under it all.” He regretted that very few of the men constructing the fair met his high standards. “The rest have to be pounded every hour of the day, and they are the ones who make me tired,” he confessed with impatience and fatigue.

|

Burnham was and remained immensely proud of the results—he installed the fireplace from the Jackson Park cabin in his house in Evanston—and of the praise he received for his achievement. Even before the fair opened, architects and other cultural leaders in New York saluted his achievement at a dinner in that city. The Association of American Architects elected him its president in 1893 and 1894. In the latter year Northwestern University awarded him an honorary doctorate, while Harvard and Yale, which young Daniel Burnham had unsuccessfully aspired to attend, acknowledged his accomplishments with honorary master’s degrees.

While working on the fair, Burnham developed some of the most important personal and professional relationships of his career, notably with architects Charles F. McKim (of the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White) and Charles B. Atwood, and with sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Burnham brought Atwood into his practice to assume many of the design duties that Root formerly performed. Burnham the fair builder established certain work methods that he followed in future planning endeavors. He set up shop for the plan of San Francisco, as he had done in Jackson Park, in a temporary structure atop Twin Peaks, from which he and his staff could view the object of their labors. For the Plan of Chicago he ordered a special penthouse constructed on the roof of the Railway Exchange Building that provided a panorama of the city below.

|

Burnham learned a great deal from the succession of planning projects after the fair. During their time together in Washington, D.C., McKim demonstrated to Burnham how the preparation and display of well-drawn architectural illustrations could help win public support. Burnham also continued to make key contacts. He met Charles Moore, secretary to Michigan senator James McMillan, who was chair of the Senate District of Columbia Committee. Moore later served as editor of the Plan of Chicago and wrote the first biography of Burnham. In his entire planning career, the only time Burnham accepted a fee was for the Cleveland plan, and he evidently did so in order not to embarrass his associates John M. Carrère and Arnold W. Brunner, who, unlike Burnham, needed the income. One aspect of Burnham's administrative acumen was his ability to entrust the day-to-day management of D. H. Burnham and Company to others while still ensuring that the jobs kept coming and that the office completed them successfully.

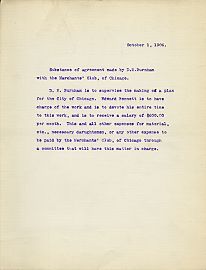

Burnham complained occasionally about the amount of time he spent away from his own practice. He often tried to make sure that expenses were covered, however, and that others who worked with him were suitably compensated. For instance, Edward Bennett received a salary of $600 a month while assigned to the Plan of Chicago. It is also likely that the prestige and visibility of the planning projects were good for D. H. Burnham and Company. But it would be a disservice to Burnham to undervalue in any way the countless hours and all the thought, labor, and personal substance he donated to these projects, as well as the sincerity and idealism with which he approached them.

Enter the Merchants and Commercial ClubsViewed in retrospect, the alliance of Daniel Burnham with the men of the Merchants Club and Commercial Club to create the Plan of Chicago appears natural to the point of inevitable. Burnham was, after all, very much one of them, having been elected to the Commercial Club in 1901, and he shared the Republican politics of the members of both organizations, their pride in their personal achievements, their belief in the efficacy of decisive action, and their commitment to Chicago, as demonstrated by their extensive service on the boards of multiple civic, cultural, and charitable organizations. He also shared their high-intentioned if sometimes self-righteous trust in their own motives and ideas. Like them, he saw no conflict between his (and their) best interests and those of the city as a whole.

|

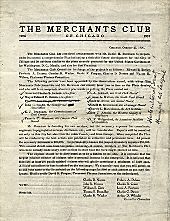

The Commercial Club dates to 1877, when thirty-nine leading businessmen, inspired by a visit to Chicago by members of the Commercial Club of Boston, founded their own similar organization. They defined their central purpose as "advancing by social intercourse and by a friendly interchange of views the prosperity and growth of the city of Chicago.” The club limited its membership—the original number was sixty—to men representing a range of commercial interests. They convened regularly at the Chicago Club and similar venues (the Commercial Club never constructed a building of its own) for business meetings, followed by dinner and discussions that usually featured presentations by an invited speaker or speakers, often one or more of their own members. The schedule varied over the years, but the form and purpose of the meetings remained fundamentally the same.

Qualifications for nomination and election included what the official history of the Club calls “conspicuous success.” In choosing new members, the club also looked for “interest in the general welfare” evidenced “by a record of things actually done and of liberality, as well as by willingness to do more,” not to mention “a broad and comprehending sympathy with important affairs of city and state, and a generous subordinating of self in the interests of the community.” Membership carried with it rigorous requirements for attendance at meetings and participation in the club’s initiatives. The Merchants Club, founded in 1896, had much the same size, purpose, and structure as the Commercial Club, though its roster was intentionally younger since only men under forty-five were eligible for election. One of the motivations for the clubs’ merger in 1907 was to join forces to create a plan for Chicago.

|

The speaker lists of both clubs—dominated by statesmen, politicians, academics, scientists, clergymen, experts, reformers, and cultural leaders of high achievement and reputation—reflected their memberships’ power and prestige and also their abiding interest in the well being of the city they had helped make and that had rewarded them so amply. Both clubs were addressed by presidents of the United States. Among the topics of the Commercial Club’s first year of meetings were “Compromise with Fraud,” “The Situation of Our Municipal Affairs,” and “Our City Streets,” as well as current trade and taxation policies. The members took up other thorny matters, such as pollution, unemployment, labor violence, and, at a meeting of the Merchants Club at which the noted African-American educator and spokesman Booker T. Washington spoke, “The Negro Problem in the South.” The Merchants Club also invited New York-based reformer Jacob Riis to share with them his thoughts on the playground movement, while the Commercial Club hosted Jane Addams on the same topic.

By the time of the Plan of Chicago the collective memberships identified among their most important works the founding of the Chicago Manual Training School and other similar institutions aimed at assisting Chicago’s working class, reducing the costs of loans taken out by wage earners, public school reform, establishment of the Chicago Sanitary District, exposure and punishment of crooked local officials, helping stage the World’s Columbian Exposition, and donating to the federal, state, and city government, respectively, the sites for Fort Sheridan and the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, the Second Regiment Armory, and a new playground on the Northwest Side.

“The Man” is HiredThe members of both the Commercial and Merchants clubs believed in the ethos of the City Beautiful movement. They were certainly aware of the proposal (described in Antecedents and Inspirations ) that Burnham had put before the South Parks commissioners, at the prompting of commission president James Ellsworth, to use landfill to construct a downtown lakefront recreational area connected by lagoon and parkway to Jackson Park. Ellsworth was a charter member of the Merchants Club. In February of 1897 Burnham spoke to this group on “The Needs of a Great City” at its first meeting after it was organized. He was back less than two months later to talk about “The Improvements of the South Shore.” A week before that, he and Ellsworth had discussed the question of “What Can Be Done to Make Chicago More Attractive?” at a meeting of the Commercial Club.

|

In 1901 wholesale grocer Franklin MacVeagh, a former president of the Commercial Club and a mainstay of several other civic-minded organizations, first proposed that Burnham and the club combine to consider how the city’s built environment could be improved. Little came of this proposal in Burnham’s own city, though he meanwhile developed his ideas for Washington, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Manila. Burnham spoke again before the Merchants Club in February 1903, however, on “The Lake Front.” That summer, Merchants Club members Frederic A. Delano and Charles D. Norton asked club president Walter H. Wilson to organize a dinner to honor Burnham and his fellow Washington planners. Delano was general manager (soon president) of the Wabash Railroad, and he later served as Chairman of the National Resources Planning Commission in his nephew Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration. Life insurance executive Norton would become chief assistant to MacVeagh after the latter was appointed secretary of the treasury under Taft. Wilson worked in banking and real estate. An undisguised purpose of the dinner was to drum up interest in developing a plan for Chicago. Wilson agreed to manage this event, but Burnham caused its cancellation since discussions of implementing the Washington plan were at a politically delicate stage.

The Merchants Club persisted. In the summer of 1906, another of their members, Chicago Tribune publisher Joseph Medill McCormick, talked with Burnham about creating a plan for Chicago. This conversation took place as both were aboard a train carrying them home from San Francisco, where Burnham had been trying without success to convince authorities in the post-earthquake city to adopt his plan for it. Burnham was intrigued, but he advised McCormick that “the work contemplated will be an enormous job.” In Burnham's opinion, Chicago's acceptance of a plan could “only be brought about after a hard fight by some public spirited organization.” No organizations were better suited than the Merchants and Commercial clubs, however, since they represented the “property interests” that would be most affected.

|

Alerted by McCormick, Delano and Norton approached Burnham right away. Burnham told them that courtesy required him to speak with MacVeagh. He did so, and MacVeagh responded that he was "extremely glad" to hear that members of the Merchants Club had pursued the idea of a plan "for Chicago's development and security, in the present and future, along lines of beauty and convenience." He was also delighted that Burnham was willing to work with them. “You are the man,” MacVeagh assured Burnham, “and that, as you well know, I have all the while perfectly understood.” The Commercial Club was at the moment preoccupied with finding a site for the Field Museum, a matter complicated by Marshall Field’s death in January of 1906. MacVeagh said that he “heartily approved” of letting the Merchants Club take the lead. Speaking for his colleagues at the Commercial Club, he assured Burnham that “what we all wish is to get you at work—and to accomplish the thing.” Burnham shared MacVeagh’s letter with Norton, informing him, “I am now ready whenever you are.”

Planning the PlanBurnham, who by this time was arguably the most experienced urban planner in the country, considered what he would require. He prepared a memo saying he needed plenty of office space, a chief assistant (the position Bennett would assume), and as much help, “expert and routine,” as the job demanded. As for how to proceed, Burnham stated, “General studies to scale should be made until by logical exclusion, a general plan plainly justifying itself shall have been worked out.” The details would follow. Even at this preliminary stage, when work on the actual design had not even begun, Burnham looked ahead to “the presentation of it in large and in small, by plans, sections, bird’s-eye views.” He recommended that “finally, the whole thing should be printed with complete illustrations.” Burnham also specified that he would be indisputably in charge and would report to the club alone, though he would consult with others as the need arose.

|

Meanwhile, Norton discussed with the Executive Committee of the Merchants Club how to estimate costs, as well as how to galvanize the membership and the city into action. He suggested that a group of members, himself included, might get things under way by agreeing to underwrite the project, their financial commitment to be reduced by the amount that other individuals subsequently subscribed. On September 17 the Executive Committee endorsed the proposal and entrusted Norton, Delano, and Wilson to take the lead. By October 1 the three had hammered out the substance of an agreement with Burnham, who advised them about which individuals to keep informed and to invite to a forthcoming banquet at which the project would be announced. The list included colleagues and acquaintances from Burnham’s earlier planning work, numerous congressmen, and other federal office-holders. “The presence of the national officials,” Burnham explained, “will help the Washington, as well as the Chicago[,] work, and the occasion is sure to bring about a realization of the seriousness of the peoples’ purpose to do away with disorder and to substitute civic beauty and convenience.”

The Executive Committee of the Merchants Club called for a closed meeting on October 19 at which the prospective plan for Chicago was one of two major agenda items (the other was reform of the administration of the public schools). The committee members hoped that the club would endorse the project “on the understanding that such approval commits every member to give his enthusiastic support and co-operation” to Finance Committee chair Wilson. This meant pledging funds and, very possibly, joining the planning effort. They estimated that $25,000 was the minimum sum required to produce a plan, and that substantially more would be needed to promote its implementation after it was released. While Wilson and others who were committed to the project agreed to guarantee financing, they continued to expect that individual contributions from members and the broader public would be generous.

|

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.