| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

|

The members of the Merchants and Commercial Clubs were very successful men of affairs who were accustomed to dealing with large-scale enterprises. They also had an extraordinary record of constructive civic engagement. They commissioned Burnham to lead them because, as Franklin MacVeagh had observed, he had demonstrated that he was so obviously the right man for this particular project. His firm had designed the buildings in which many of their set lived and worked, he had overseen the construction of the fair that had done Chicago so proud, and he had prepared plans for other major metropolises. Indeed, Burnham's multiple accomplishments had put the idea of remaking Chicago in their minds in the first place. They trusted his judgment, shared his vision, and admired his reputation for achieving great things. But they had staked a claim every bit as good as his that Chicago was their city. They were as prepared as was he to show their commitment to Chicago, they believed that they were as qualified to act in what they saw as its best interests, and both they and he knew that their participation and backing were crucial to the creation and implementation of any plan on this scale. It is unlikely, however, that when they began their work they knew just how demanding a task they had set for themselves and how large a commitment was required.

|

|

Daniel Burnham was not present on October 29, 1906, as six members of the Merchants Club convened for the first meeting on preparing the plan authorized by the club. At that point they had yet to decide what to call the committee on which they were serving. The typed minutes of the meeting leave a space for its title. Someone has handwritten in this space "(Name to be decided)." Soon they would be the Committee on the Plan of Chicago. After the merger of the clubs early in 1907, there would be a larger General Committee, members of which would chair subcommittees on specific parts of the city that the Plan would address: the lakefront, the boulevard to connect the North and South Sides, and railway terminals. By 1908 these had evolved into committees on lake parks, streets and boulevards, interurban roadways, and finance, as well as railway terminals.

|

The planners devoted their first and several succeeding meetings to figuring out how to raise the money required to produce a plan. Burnham meanwhile took charge of two other areas: defining and prioritizing the key elements of Chicago that the planners would address and gathering the relevant information necessary to understand current conditions and calculate projections about the future. The committee members shared with him the demanding duties of lobbying local and state political and business leaders for the purpose of encouraging their support (or at least reducing their opposition) to what the club would propose. They also assisted him in attempting to control when, how, and among whom the planners' work would be publicized. If Burnham was not at the first meeting, he was the dominant presence at many others. He hosted dozens of these sessions in the offices of D. H. Burnham and Company on the fourteenth floor of the Railway Exchange Building. He put a small team of draftsmen to work under the supervision of Bennett in the special rooms he had constructed on the roof of the building, overlooking Michigan Avenue, Grant Park, and, slightly to the north, the Art Institute.

|

|

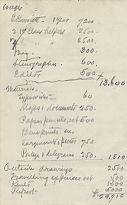

The club's main strategy to pay for production costs was to sign up subscribers. To do this, it took full advantage of its well-heeled members and their networking ability. In exchange for contributions, fund-raisers offered subscribers the prestige of being associated with this effort and the satisfaction of having demonstrated their civic faith and loyalty. With remarkable speed, the subscription campaign reached its initial target of finding three hundred people who would pledge $100 each. By the end of 1907 the planners were asking for additional pledges of $300 spread over three years. Their target was now $100,000, which they calculated as the cost not only of finishing the Plan, but also then publicizing it sufficiently to win endorsement by the city.

|

There were a few petty squabbles among these practical men of means over the precise costs for this and that, and over who should pay for what, even including some testy correspondence about the price of the lunches served at meetings in Burnham's office. The unity, dedication, and generosity of these strong-minded individuals were remarkable, however. When funds grew tight, the core leadership agreed among themselves to cover expenses, whether or not these were defrayed by additional contributions from subscribers. According to the financial report the planners drew up in December of 1908, one unnamed member made a "special contribution" of $10,000 "in order that the Committee might be free to develop the Plan along the broadest lines."

Making Plans

|

|

Burnham and the members of the several Plan committees liberally exercised their considerable political clout. They discussed among themselves what laws needed to be drafted or amended, whose support they required, and how best to persuade these people. To this end, they compiled lists of local and state elected officials and commission heads. They created advisory bodies consisting of Illinois governor Charles Deneen, Chicago mayor Fred Busse, numerous aldermen, and the officers of the Drainage Board, the Board of Education, the Art Institute, the Chicago Commercial Association, the park commissions, the Western Society of Engineers, and the American Institute of Architects, among other organizations. They invited many such worthies to contribute their wisdom and experience to the planning effort. The planners were shrewd enough to hear out and not simply ignore or dismiss those with opposing views. Realizing that certain politicians and businessmen might feel that their interests were being neglected, the committee chairs tried to reassure them. For instance, Clyde Carr, chair of the committee dealing with the proposed Michigan Boulevard, told Burnham that he asked the president of the Real Estate Board to stop by Burnham's office to receive a personal update, "as I am anxious to have all the support possible from this Real Estate Board."

On occasion the planners traveled to Springfield to confer with state officials. They had a special interest in the municipal charter reform referendum of September 17, 1907, which, if successful, would increase local authority in ways Republican businessmen like the members of the Commercial Club favored. This measure was defeated by the voters, however. Early in 1907 the planners organized a discussion with the commissioners of the South Park board, whose approval they needed for any proposals affecting the lakefront from Grant Park south. In the fall of the same year, they started arranging special viewings of their work to date in the Railway Exchange rooftop drafting rooms for those they wished to impress. Among the organizations they hosted were the Industrial Club (with which the Commercial Club merged in 1932) and the Chicago Association of Commerce. On October 30 they waited upon the mayor, the corporation counsel, the chair of the board of local improvements, and the First Ward aldermen Mike "Hinky Dink" Kenna and "Bathhouse" John Coughlin. The inclusion of politicians whose scruples many reformers and, doubtless, members of the Commercial Club found highly dubious indicates how flexible and pragmatic the planners were in their efforts to generate support for their work.

At the other end of the city's political spectrum from Kenna and Coughlin was Jane Addams, with whom they also consulted. Addams was among the many West Siders the planners polled on the widening of Halsted Street. According to an internal summary of her response, Addams said Hull House would not oppose the change "if it were a part of a well considered scheme for the general improvement of the city." Small as her role was in shaping the Plan of Chicago, Addams was among the very few women who had any part at all in the preparation of the Plan. This is, regrettably, not surprising, since very few Chicago women ran large businesses and, until 1914, none could vote. What is remarkable, however, is the extent to which prominent people like Addams and even the mayor and governor seemed to concede the authority of Burnham and other members of the Commercial Club—who were a few dozen individuals in a small private organization—to propose major changes that affected all Chicagoans.

The Burden of Work

|

|

|

The Michigan Avenue proposal involved a multi-part plan to widen and elevate that street for several blocks above and below the Main Branch of the Chicago River and to connect the north and south segments with a double-level bridge. This would transform Michigan Avenue into a continuous boulevard linking the North and South Sides. The Chicago River and lakefront discussion considered whether and how much to devote the shoreline near where the river met the lake to harbor facilities for Great Lakes commercial shipping. In regard to the railway terminals, the planners hoped to reduce inefficiency and congestion by keeping freight passing through Chicago out of the downtown and by reorganizing the placement of passenger stations in the heart of the city.

|

The Commercial Club pulled out all the stops in support of its Michigan Avenue plan, spending several thousand dollars to hire a publicist and producing a special booklet devoted to this single improvement before the Plan of Chicago as a whole was published. As Burnham had anticipated, other groups proposed contrasting designs in the period the Plan of Chicago was being prepared. The Michigan Avenue Improvement Association, for example, called for a single-level bridge and for a boulevard only a hundred feet wide, issuing a pamphlet of its own that praised its plan as simple, aesthetically appealing, relatively inexpensive, and free of legal obstacles. For over two years, Burnham urged his colleagues to stick to the "ideal" scheme of widening the avenue as much as possible (which they calculated at 246 feet), elevating it to create two levels, and building a double-decker bridge across the river with plazas on both sides of the upper level. The planners tried to win over property owners in the area by arguing that widening the street would raise land values. Michigan Avenue was the main topic of the meeting with Mayor Busse, Aldermen Kenna and Coughlin, and other city officials in late October 1907.

|

The discussion of the future of the lakefront, which began shortly after the fair, intensified in the first decade of the twentieth century. This discussion focused not only on what to do with Grant Park, but also on whether maintaining and developing the shore as a public park would jeopardize the city's commercial well-being. As Governor Deneen was about to sign a bill passed in April 1907 that would authorize the construction of a shoreline parkway from Grant Park to Jackson Park, he received a letter from the most persistent opponent to this plan, Colonel W. H. Bixby, the United States Army engineer in charge of federal projects in the city. Bixby wanted to build a line of docks along the lakeshore north and south of Grant Park to serve lake-going ships. A few weeks later, Bixby wrote to Delano, "The future prosperity of Chicago is dependent upon an Outer Harbor," next to which other infrastructural improvements were "bagatelles and trifles." Early in 1908 Delano invited Bixby to lunch in Burnham's office with Burnham and the members of the General Committee and of the Committee on the Lake Front.

Bixby evidently based his view on the assumption that manufacturing and wholesale trade would continue to be located in or near the center of the city, making it important to afford ships access to this area. Whether or not he was correct, if his advice were followed, much of the downtown lakefront would be dominated by piers, railroad tracks, and warehouses. The Commercial Club responded quickly to Bixby's opposition. Norton wrote to club president John Farwell that several of his fellow planners agreed "that there is sufficient sentiment in favor of an outer harbor to make it imperative as a matter of tactics that we definitely state at this time that The Commercial Club will appoint a committee to investigate that question with Mr. Burnham." This was not entirely insincere, since Burnham and others had previously been given pause by suggestions that the city required an improved outer harbor for ships too large to use the river. In any event, they invited and received written commentary on the idea from several Chicagoans knowledgeable about Great Lakes trade.

Some of their correspondents agreed with Bixby, but the thinking that carried the day contended that the future of freight shipping lay with trains, not boats. Bennett and others also argued that Calumet Harbor provided a better port for shipping than did the stretch of lakefront nearer the center of Chicago since it was possible to provide access from there for heavy industry, which was increasingly located on the city's far South Side. In addition, concentrating large-scale shipping in Calumet Harbor would ease downtown traffic problems by reducing the number of times it would be necessary to open bridges across the Chicago River. And, of course, this would leave the lakefront closer to the river free for recreational development.

|

When Charles Norton wrote to hardware wholesaler Adolphus Bartlett in February 1907 about Bartlett 's possible service on the Committee on Railway Terminals, Norton described the relocation of passenger stations as "the one greatest problem which confronts Mr. Burnham in preparing his Plan of Chicago." Moving terminals would affect some twenty competing private railroad companies. In addition, any such changes would necessitate a rearrangement of roads, streetcar lines, elevated trains, subways, and other elements of the urban infrastructure. But virtually everyone agreed that something had to be done. The planners' solution was to use their influence in the business community to get the top management of the different railroads to sit down together and talk directly to one another. They wrote to the heads of all the railroads doing business in Chicago, inviting them or designated representatives to a buffet lunch and full afternoon meeting to take place on July 14, 1908, in Burnham's office.

The minutes of this meeting reveal that Burnham and planning committee members told their guests that the purpose of the gathering was "to obtain a means of free communication" between the Committee on Railway Terminals and the railroads, with the purpose of "harmonious work to a common end, and the securing of a Plan which would have the co-operation and approval of the railroads." The planners presented their ideas on what to do about rail congestion and inefficiency and then left their visitors to discuss matters among themselves. At the close of this discussion, the railroad executives thanked their hosts and then enigmatically stated that they desired to assure the committee "that we intend to co-operate with you as far as we can—at least up to the point of a full discussion of what may or can be done and when we can do it." The issue remained unresolved and under discussion for years after the Plan of Chicago appeared.

Toward Publication

|

Several months before Burnham completed his draft, he and Bennett had secured the services of a group of seven gifted artists to prepare the drawings that would accompany the text. Burnham was convinced that making the Plan of Chicago's ideas visually compelling and seductive was vital to winning Chicagoans over to its proposals. Jules Guerin (as his name appears in the Plan, though in his correspondence with Burnham he signed it Guérin) and Fernand Janin were the most significant illustrators. Guerin, born in St. Louis in 1866, was a painter, illustrator, and muralist who had done some of the renderings for the Washington plan. His work graced the pages of leading magazines and, in the years to come, Pennsylvania Station in New York, the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. His depiction of the parade scene from Aida on the decorative fire curtain of the Civic Opera House (1929)—done in a striking combination of rose, pink, olive, gold, and bronze—pleases Chicago audiences to this day. Bennett evidently knew the Parisian Janin, who executed the major elevation and perspective drawings, from his own student days at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Janin was only in his late twenties when he worked on the Plan.

|

|

The planners entrusted publication to the Lakeside Press of Commercial Club member Thomas Donnelley, who supervised the production. They had originally projected an edition of 1,000 copies, but they raised this to 1,650, including 100 copies ordered by Burnham and 50 by Norton. They decided to issue this volume as one might publish a fine art book, in what one member called a "deluxe limited special edition" with an individual number assigned to each copy. This would reward subscribers and impress readers. Bennett created a Commercial Club cipher for the cover. The originally scheduled date of publication, set perhaps unrealistically early, was pushed back a few times. On January 28, 1909, the planners met to discuss the proofs of the first six chapters. On March 14, they blessed the entire text with their approval. Finally, on July 4, 1909, the Plan of Chicago was ready for all the world to see.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.