| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

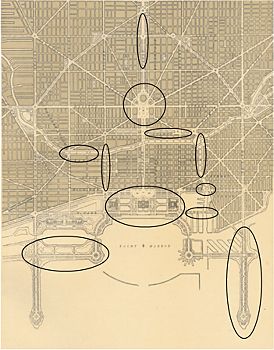

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

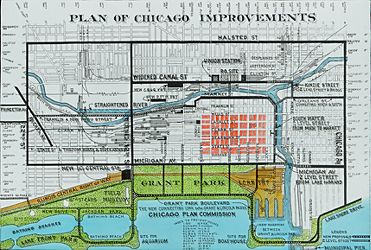

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

Trying to determine the extent to which the city of Chicago implemented the Plan of Chicago is a complicated task. The Plan includes recommendations that were proposed in one form or another before the Merchants Club hired Daniel Burnham, and so these proposals cannot be attributed solely to the Plan, whether they were followed or not. Among these recommendations are the "boulevarding" of Michigan Avenue, the creation of more parkland along the lake with fill, and the landscaping of Grant Park in a formal rather than "natural" style. In other instances, ideas suggested by the Plan underwent considerable modification along the way to realization. The design of Wacker Drive, for example, did not rise to the standard of the civic art that Burnham championed in his desire that the Chicago River would evoke the Seine and the city as a whole resemble Paris.

Some have also argued that the Plan did not make much practical difference in the evolution of Chicago's built environment. They claim that the city would have done several of the things the Plan proposed—such as widening many streets, building Union Station, and establishing the forest preserve—whether or not it had been published. One could add that since Chicago rejected or at least failed to implement as many of the Plan's recommendations as it adopted—most notably the monumental Civic Center at Congress and Halsted—this makes it even harder to say what the Plan's precise influence has been. By this logic, the Plan of Chicago's fame is perhaps attributable less to the fact that it was so directly and extensively implemented than to the high profile of Burnham and the Commercial Club, the eloquence of the Plan's prose style, the splendor of Guerin's and Janin's drawings, and the energy of Wacker and Moody.

|

The implementation of the Plan of Chicago is inseparable from the continuing efforts to promote it. During his nine years as managing director of the Chicago Plan Commission, Walter Moody seized every chance he could find or his ingenuity could create to sell the idea of planning and the contents of this particular plan to virtually every man, woman, and child in the city. When World War I disrupted Chicago's economy, Moody issued a pamphlet declaring that a top priority was to provide employment for returning soldiers, and that the Plan provided a splendid way to find them jobs. "The best opportunity for this is work on Chicago's great public improvements," he wrote. Moody even raised the enactment of the Plan to a sacred calling. On Sunday, January 19, 1919, some eighty Chicago churches participated in what were called Nehemiah Day services. The ministers of these congregations agreed to take the words of the Old Testament prophet Nehemiah—"Therefore we, His servants, will arise and build"—as the basis of their sermons, in which they would advocate the implementation of the Plan of Chicago.

|

Moody died in 1920 at the age of forty-six. Eugene Taylor, his associate on the Chicago Plan Commission staff, succeeded him as managing director and remained in the job for the next twenty-two years. The commission continued to publish booklets with attention-getting titles, such as 1921's An Appeal to the Businessman, which argues that the best way to reduce local unemployment was to undertake construction projects of the kind the Plan proposed, a suggestion that the federal government followed during the Depression years of the 1930s. In 1924 the commission produced An S-O-S to the Public Spirited Citizens of Chicago, which chairman Charles Wacker described in a speech as "a warning to the citizens not to lag in their support of the Chicago Plan." Wacker stated that Chicagoans "must push the projects in the Plan to a speedy completion." He also appealed to the state legislature to increase the city's ability to borrow money for such projects. Wacker's remarks came in his 1926 farewell address as chairman of the commission after seventeen years of extraordinary service. James Simpson, the head of Marshall Field's, took over for the following nine years.

The commission's aims, composition, and status changed considerably over time. Moody's death and the inevitable decline in zeal from the first group of commissioners' initial dedication led to a reduction in the Commission's activities, including the disappearance of Wacker's Manual from the schools. Several of those who once devoted themselves single-mindedly to the Plan's implementation now focused on other, albeit related, efforts. One of the most important of these was Chicago's earliest zoning regulations. Edward Bennett, now consulting architect for the Chicago Plan Commission, helped draft the 1923 zoning ordinance. Both Charles Wacker and Eugene Taylor served on the new Zoning Commission, which dealt with some of the issues that were previously on the agenda of the Chicago Plan Commission. By the 1930s the number of the commission's members had diminished, and new appointees had different priorities than the original ones. In 1939, against the advice Walter Moody had once given, the commission became part of the city government rather than an external semi-public advocacy group. Its size was reduced to twelve members, and it had little effective power.

The name "Chicago Plan Commission" has persisted through a number of administrative reorganizations, including the establishment of the Chicago Department of City Planning in 1957, which itself has undergone multiple permutations. Today the Chicago Plan Commission is part of the city of Chicago's Department of Planning and Development. It consists of nineteen people, including aldermen, other public officials, and citizens appointed by the mayor, who is also a member. Its primary duties are to approve or disapprove of proposals by any public body or agency to acquire, dispose of, or change any property in the city, and to review certain land-use proposals, including those relating to lakefront preservation. It does not have statutory power to enforce its decisions, however.

|

In many respects, the three-decade era of the Chicago Plan Commission as originally constituted was a great success. Moody, Taylor, Wacker, and Simpson developed a working relationship with a series of mayors between 1909 and 1931, starting with Fred Busse and including Carter Harrison II, William Hale Thompson, William Dever, and then Thompson again. They also were able to convince voters to fund commission-supported initiatives. Between 1912 and 1931, Chicagoans approved some eighty-six Plan -related bond issues covering seventeen different projects with a combined cost of $234 million. Only at the end of the period did voters begin to turn down bond issues. This was due to the scandals in the administration of Thompson, who barely evaded prison but nonetheless trounced the honest and capable Dever in the 1927 election.

From Plan to Action

|

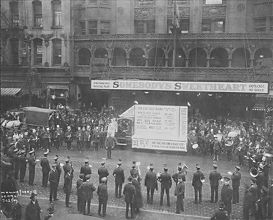

The voters approved the first of two Twelfth Street bond issues in 1912, but work did not begin until four years later because of legal actions regarding compensation for seized property. On December 20, 1917, the city marked the completion of a portion of the work with a civic celebration that drew an estimated 100,000 people. From a speakers' stand erected at Twelfth and Halsted Streets, County Judge Thomas F. Scully told the crowd, with typical Chicago modesty, "We are here tonight to do honor to the greatest public improvement ever completed by this or any other municipality in the world." Continuing legal problems and difficulties in obtaining steel for civilian purposes during World War I delayed the bridge's construction. In addition, another bond referendum was required in 1919. In 1927 the commission proudly reported that the entire project was almost finished, with the notable exception of the bridge, which could not be completed until another commission recommendation, the straightening of the Chicago River, was accomplished.

|

Two other major street projects involved Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive. Their improvement followed a sequence of steps similar to the Twelfth Street widening. As might have been predicted, the commission's Michigan Avenue proposal faced delays due to stiff resistance from local property owners (opponents hired more than two hundred lawyers), as well as to wartime shortages. While Michigan Avenue as actually reconstructed does not precisely resemble Guerin's renderings, the city did substantially adhere to the Plan of Chicago's recommendation that the street be transformed into a much wider two-level boulevard that crosses the river by means of a double-decker bridge.

|

The commission recommended in 1917 that the city convert the crowded South Market Street wholesale area just south of the Main Branch of the Chicago River into a double-level public thoroughfare. This adhered to the Plan's goal of routing commercial traffic around the Loop while also making the riverfront more attractive. The ensuing project required a heroic feat of civil engineering. Work began in 1924 and proceeded one section at a time, with crews digging twenty-four hours a day to get down to the bedrock 118 feet below, then pouring thousands of yards of structural concrete in record time. On October 20, 1926, Mayor Dever officiated at the opening of the new roadway. Upon taking office in 1923, Dever had appointed A. A. Sprague II, a member of the Commercial Club and a Plan advocate, commissioner of public works. Charles Wacker, after whom the new thoroughfare was named, was too ill to attend the opening.

Of other road projects suggested or inspired by the Plan, the extension of Ogden Avenue northeast from Randolph Street to Clark Street (later shortened to terminate, except for an isolated segment, at Chicago Avenue) was the only new major diagonal constructed of the several that the Plan had recommended. Many other existing streets were widened, however, including twenty-six miles of Western Avenue and twenty miles of Ashland Avenue. Sheridan Road was likewise enlarged to accommodate increased traffic, though it was not made into the highway to Milwaukee that the planners had called for. The major roadways encircling the city at different distances were also improved, as the Plan had also proposed, and a Chicago Regional Planning Association was established in 1923 with the responsibility of administering area highways. Just as the Civic Center was never built, Congress Street never became the major east-west "Axis of Chicago" that Burnham and his fellow planners had eagerly desired.

The River and the Rails

|

With the railroads pushing for the construction of a new Union Station that would serve multiple passenger lines (also proposed by the Plan of Chicago ), the Chicago Plan Commission helped persuade the city council to include in the ordinance approving the station a provision for straightening the South Branch, along with several other street-improvement and bridge-construction recommendations from the Plan. After considerably more negotiations, studies by the new Chicago Railway Terminal Commission, and agreements about the railroad property transfers that would be necessary if the city changed the river's course, the city council passed an ordinance on July 8, 1926, to straighten the river between Polk and Eighteenth Streets. Voters passed the related bond issue in the election of April 5, 1927, and by 1930 the city had completed the project. The north-south streets west of Clark Street and east of the Chicago River were not extended southward significantly, however.

|

The Lakefront and the Parks

|

The Plan of Chicago called for transforming the city's lakefront by means of filling and landscaping into one continuous and spectacular public park that would enable more people to enjoy the city's most wondrous natural feature. The filling of the lakeshore south of Fourteenth Street began in 1917 and reached Jackson Park thirteen years later, but the long lagoon Burnham had first designed in the 1890s was not built. The city did construct beaches and other amenities, however, as well as Soldier Field (1924, 2003), located just south of the new Field Museum. East of Soldier Field and the Field Museum, it created Northerly Island, which follows the Plan quite closely. The filled land that constituted the access to Northerly Island and the island itself became the site for the Shedd Aquarium (1929), the Adler Planetarium (1930), the Century of Progress Exposition of 1933-34, and, shortly after World War II, the Meigs Field Airport. Lincoln Park, meanwhile, expanded farther northward and outward, reaching Diversey Parkway by the early 1920s, Montrose Avenue by the end of the decade, and Foster Avenue by 1933 (it did not extend to its current northern terminus at Hollywood Avenue until the 1950s). In 1916 the city constructed Municipal (soon Navy) Pier, one of the two man-made extensions into the lake recommended by the Plan, though the city built the pier at Grand Avenue and not, as the Plan had recommended, at Chicago Avenue. The pier's southern counterpart, at 22nd Street, was never constructed.

|

|

|

The Plan urged the building of more parks and playgrounds in the city and the setting aside of natural areas in Chicago and nearby for recreation. This was in keeping with policies formulated by the Special Park Commission and the Outer Belt Commission in the first years of the twentieth century. The development of the lakeshore was the Plan's most dramatic influence on park development, but the impetus the Plan gave to the forest preserve was much larger in scope. The Forest Preserve District of Cook County was approved by the voters in 1914 and established the following year, with Charles Wacker on its board. In 1916 it acquired its first new land, located in northwest Cook County in the area now known as the Deer Grove Forest Preserve District. The district soon added portions of the Skokie Valley. In 1921 it received a gift of eighty-three acres from Edith Rockefeller McCormick, the daughter of John D. Rockefeller, primary benefactor of the University of Chicago, and the wife of Harold McCormick, who had served on the Commercial Club's Committee on Lake Parks. This donation, to which was added over a hundred more acres purchased by the district, became the site of the Brookfield Zoo. By 1925 the Chicago Plan Commission proudly reported that the Forest Preserve District had acquired another 30,000 acres of land in a broad belt "from the shore of the lake at the Indiana state line on the south to the edge of the lake again near Glencoe at the north."

Civic BuildingsIn the best Progressive tradition, the Chicago Plan Commission bemoaned the inefficiency of the organization of government agencies. In 1920 it estimated that the scattering of municipal offices throughout the city cost taxpayers an extra $75,000 a year, and that the new (and still current) City Hall had been too small even at the time it was dedicated in 1911. But the Plan's most original suggestion, a unified civic center set on a vast plaza, never generated the enthusiastic support required to make it possible. Another project that occupied much of the commission's attention did come to fruition, however: a central United States Post Office on the Near West Side that could handle the astonishing volume of mail entering and leaving Chicago. The Chicago Plan Commission noted that just the increase in mail since the existing main post office was erected in 1906 was greater than the combined 1919 volume of Boston, Detroit, Cincinnati, Kansas City, and Jersey City.

|

The commission complained that mail service was getting progressively slower, and that it would "break down absolutely in two years if prompt relief is not had." It recommended a two-block site on Canal Street between Madison and Adams as being ideally accessible to all parts of the city and to nearby railroad stations. In June 1919 the postmaster general appointed a committee to examine the situation, with the omnipresent Charles Wacker as its chair. By 1927 the government acquired an enormous site, on Canal Street between Polk and Harrison, just to the south of where the commission recommended. The structure, the largest post office in the world at that time, opened in 1932. It was succeeded as the city's main mail-handling center in 1996 by the much smaller and more automated General Mail Facility across the street.

The Hand of Burnham and Bennett

|

|

|

Bennett continued to get important work, including several buildings at Chicago's 1933-34 World's Fair. He became chairman of the board of architects directing the design of the buildings in Washington's Federal Triangle, located north of the eastern section of the Mall. His firm of Bennett, Parsons, and Frost designed the Apex Building, completed in 1938 at the western tip of the Triangle. This was the last major work by Bennett, who died in 1954. His planning career thus concluded where Daniel Burnham's had begun, at the site of his senior associate's contributions to the Senate Park Commission at the turn of the century.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.