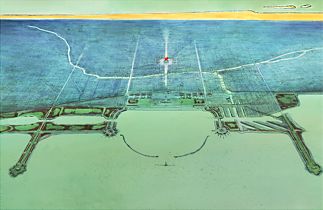

Lantern Slide Show

|

Handsomely produced and lavishly illustrated, the

Plan of Chicago

was its own best advertisement. But the men who created the

Plan

had no intention of limiting their labors only to preparing and publishing the

Plan,

as massive an effort as that was. They never assumed that the people of Chicago, without considerable additional urging, would immediately grasp the irrefutable logic of the

Plan's proposals and then rush to implement them. The planners also knew that the meetings they held with various groups and individuals as the

Plan

was being developed, and the limited edition of copies of the

Plan

they printed, reached only a very small if influential segment of the population. Even before they had formulated any specific recommendations for improving Chicago, they began a strategy for the figurative selling of whatever these recommendations might be to government officials, the business community at large, property owners, and voters. The

Plan

itself was forward-looking, but in some respects the publicity techniques the planners used to generate support, especially after its release, were even more innovative and modern.

Rallying the Faithful, Managing the Press

Invitation and Solicitation

|

The members of the planning committees made sure first of all that they maintained the interest and support of their core constituency, the subscribers who funded the

Plan of Chicago.

The

Plan

prominently acknowledges these people in its opening pages, where it lists the names of the fourteen businesses, one law firm, two estates, and 312 individuals (308 of them men, judging from their names) who contributed prior to June 1, 1909. The planners, who were virtually all among the listed contributors, had also been solicitous of the subscribers while work was in progress. In addition, they made sure that the general membership of the Commercial Club was well informed. On January 25, 1909, Burnham was the featured speaker at a closed meeting of the club at the Congress Hotel that was devoted to the

Plan.

He illustrated his talk that evening with scale models, carefully mounted drawings, and thirty-five lantern slides.

Campaign of Education

|

Burnham and the committee members discussed at length how to ensure the most positive public reception—and one likely to translate into action—once the

Plan of Chicago

appeared. As early as their third meeting, minutes of this meeting reveal, they had agreed "that a certain amount of money must be set aside to carry on a campaign of education on behalf of this Plan of Chicago, with lectures in Public Schools, etc., to show what was proposed in this matter here and had already been done in similar matters elsewhere." The question that occupied them the most at this point was how to deal with the press. Keeping up good relations with newspaper editors and reporters was particularly important because, in an age before radio and television, print was by far the public's major source of information. Since Chicago was served by a dozen daily

newspapers

that competed with each other for newsworthy stories and expressed different political outlooks, shaping opinion was a challenge.

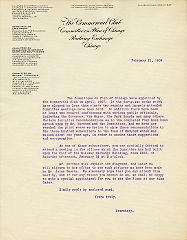

A Carefully Preared Statement

|

The planners wished to maintain secrecy when it seemed advantageous to do so, but also to get ample and positive news coverage when that was useful. Their inability to control either the timing or the content of coverage proved irritating to these businessmen, who were used to giving orders and having them followed. A week before Burnham was to describe the

Plan

to the Commercial Club membership, club secretary John Scott wrote to

[

Tribune

]

publisher and club member Joseph Medill McCormick. Scott requested that "the Closed Meeting on the 25th instant be given no publicity," pressuring McCormick by adding that "the members bespeak your courtesy in the matter." McCormick said that as a member he was honor bound to treat the meeting as confidential, but, he advised

Plan of Chicago

General Committee chairman Charles Norton, "You know by this time that it is impossible to keep news out of all the papers and therefore out of any one of them." At McCormick's suggestion, Norton prepared a disingenuous announcement stating that nothing of great importance would happen at the meeting, and he brokered an agreement among the editors of leading papers that none would cover it and so no paper would scoop the others. Just in case, when the planners met on January 23 to make final preparations for the January 25 presentation to the membership, they authorized Burnham to hire security men to ensure that no one would photograph the drawings on display.

The very fact that the Commercial Club attracted so much attention and believed it needed to take these precautions shows how powerful the press thought the club's members were. The planners, in turn, felt that the media's support was vital to their work. Members of the

Plan

committees went out of their way to acknowledge and encourage positive coverage. They sent a note to

Chicago Daily Chronicle

editor H. W. Seymour in the spring of 1907, for instance, expressing their "personal appreciation of your clear and readable [i.e., favorable] Editorial in this morning's Chronicle on the question of the North and South Connecting Boulevard." Later the same year, General Committee treasurer Walter Wilson shared a similarly laudatory editorial from the

Chicago American

with Norton, urging him to write to

American

editor Andrew Lawrence. "Ever since the bankers and 'certain portions of the administration' got [Lawrence] in line on the financial situation," Wilson explained, "we have been complimenting him to beat the band by daily telephones and letters, and I think it has done him a lot of good and opened his eyes as to what his paper might accomplish along the proper lines."

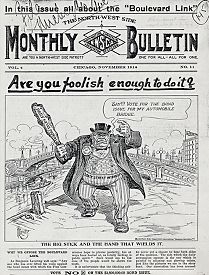

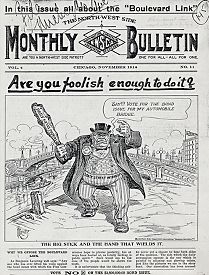

A Case in Point: Michigan Boulevard

Are You Foolish Enough to Do It?

|

The proposal to turn Michigan Avenue into a boulevard connecting the North Side and the South Side proved to be the biggest publicity headache. Some property owners, business associations, and newspaper editorials criticized and ridiculed the club's proposals. Early in the planning process, even McCormick's

Tribune

said that a double-level boulevard was a bad idea since it lacked aesthetic appeal and was unlikely to function well. After reading the editorial, Norton wrote to Clyde Carr, chair of the Committee on Streets and Boulevards, instructing him to intervene before a majority of the city's newspapers adopted a negative view of the matter "from which they will find it difficult to retire." Norton told Carr to instruct Edward Bennett—Daniel Burnham was traveling in Europe—to make "a careful and attractive drawing of the ideal scheme" for the boulevard that very morning and to schedule appointments with twelve different newspaper editors in order to demonstrate to them the scheme's merits before they committed their papers to an opposing position.

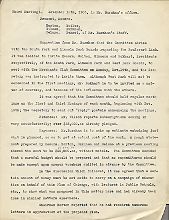

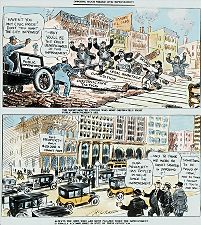

Preemptive Strike

|

This did not prevent some reporters and cartoonists from lampooning the idea of an elevated Michigan Avenue as "a boulevard on stilts." The planners told the Board of Local Improvements and anyone else who would listen that this characterization distorted the facts. Such opposition also led to their decision to publish their proposals for Michigan Avenue right away as a separate booklet and to hire

Tribune

reporter Henry Barrett Chamberlain (in some places his name was spelled Chamberlin) to work for them as a publicist. In addition, someone—possibly Burnham or Bennett—prepared a formal statement on the connecting boulevard, reminding Chicagoans that the planners had exhaustively considered all the other options for Michigan Avenue before arriving at their own recommendation. As part of this consideration, the statement explained, they had made scale models of these options. The statement invited members of the public to view the models and judge for themselves which proposal was best. It was not the planners' purpose, they claimed, "to attempt to dictate to the government or to the people of the City of Chicago."

Launching the

Plan

Report of the Publication Committee

|

The Commercial Club carefully staged the release of the

Plan of Chicago

on July 4, 1909, as a major event. A special Publication Committee, chaired by John Scott, met with Chamberlain and General Committee vice chairman Charles Wacker to discuss their strategy. Norton had by this time left Chicago for Washington and his new job as assistant secretary of the Treasury, so that Wacker was now in charge. Wacker and Scott spoke with the managing editors of the leading newspapers, including the foreign-language press, and obtained signed agreements from them to release the story on the

Plan of Chicago

in the afternoon editions of Saturday, July 3, and the morning editions on the Fourth of July. Three papers—the

Examiner,

the

Tribune,

and the

Record Herald

—published special illustrated supplements on the

Plan,

which the planners mailed to what the Publication Committee report called "a carefully selected list of one thousand names of persons in or nearby Chicago, whose interest is desired."

In May Burnham made arrangements with Commercial Club member and

Art Institute of Chicago

president Charles L. Hutchinson for an exhibition of the Guerin and Janin drawings in the Art Institute's first-floor northeast gallery. Burnham and Bennett supervised the details, from special lighting to the placement of vases and other props. The Publication Committee made sure the business community was given top priority in seeing the display. It issued three thousand free tickets to members of the Chicago Association of Commerce for a private viewing between July 5 and July 8. The committee distributed close to ten thousand more tickets to several additional clubs and associations. After leaving the Art Institute, the drawings traveled to other cities in America and Europe, including Philadelphia, Boston, London, and Düsseldorf. When there proved to be more requests to host this exhibition than the General Committee could accommodate, it offered to send sets of lantern slides.

The Publication Committee put Chamberlain in charge of distribution of the

Plan of Chicago.

He began with members of the members of the Commercial Club and

Plan

subscribers, who received them for free. He also sent more than four hundred copies to aldermen and other city and county officials, park commissioners, Chicago members of the Illinois General Assembly, other state office holders, United States congressmen, local and federal judges, the Sanitary District board, Chicago libraries and clubs, numerous magazines and newspapers, and President Taft and his cabinet. Some of the remaining copies were apparently sold for $25 each. This price was for all practical purposes out of the reach of most Chicagoans. The Commercial Club presented the ceremonial first copy, hand-bound in leather and with marbled paper insets, to Daniel Burnham.

The Chicago Plan Commission

The planners understood that if the

Plan

was to be implemented, they needed to have the support of Chicagoans who would vote on the referendums to authorize the bonds required to fund major improvements. Not trusting elected officials to take the initiative in selling the public on the

Plan,

the Commercial Club moved aggressively on three related fronts. The first was to obtain the city's formal approval of the

Plan of Chicago

as Chicago's official planning document. The second was to make sure that there was an organization actively pushing political leaders to put the

Plan

into action. The third was to convince the community as a whole of the value of the

Plan.

The effort to achieve these goals constituted one of the pioneering exercises in large-scale public relations.

Charles H. Wacker

|

Walter Wilson, who was at this time controller of the city of Chicago, took the first step toward the formal acceptance of the

Plan.

Speaking on behalf of Mayor Busse, Wilson issued a statement on July 4 praising the

Plan of Chicago's proposals as befitting Chicago's business character and "spirit of 'do.'" Two days later Busse himself commended the Commercial Club warmly and officially endorsed the

Plan.

As the planners desired, the city council empowered Busse to appoint a commission of elected officials and private citizens to consider the proposals and how to enact them. On November 1, Busse nominated and the council approved 328 men to serve on the Chicago Plan Commission, with Charles Wacker as chairman. The commission met for the first time on November 4 in the city council chamber, though half of its members were absent. Wacker's first act was to name twenty-six of their number to an executive committee "to undertake active work on a plan." Most of the Commercial Club members who participated in creating the

Plan

were on the larger commission, and several of them were on the executive committee as well.

On Saturday evening, January 8, 1910, the Commercial Club hosted the Chicago Plan Commission at a dinner at the Congress Hotel. Club president Theodore Robinson served as toastmaster, and Charles Norton returned from Washington to speak on "The Broader Aspects of City Planning." In his address, Norton was unapologetic about the

Plan's ambitions. What everyone had to realize, he explained, was that the real question was not whether it was too big, but whether it was big enough. "And when we reach that viewpoint," he continued, "we shall discover how great was the vision and the genius of Burnham." In his remarks that evening, Wacker recapitulated the

Plan's history, calling it "the best book on city planning ever published." He assured his wealthy listeners that the increased prosperity produced by the

Plan's implementation would benefit poorer citizens more than would devoting funds to housing or public services. When it was his turn to speak, Alderman Bernard W. Snow—chairman of the city council's Committee on Finance and an advocate of making local government more efficient—agreed with Wacker's contention that while the

Plan of Chicago

would cost millions to implement, this would be a good investment. Snow noted, however, that the

Plan

was not to be regarded "as anything more than a well-thought-out suggestion" that might be modified. But it was essential to get to work; otherwise the

Plan

"will sleep the sleep of the forgotten in the dust-covered tomb of the years."

A Plain Talk on the Plan

|

Snow's remarks signaled that the real promotional effort had only begun. Wacker understood this, and he drove the Commercial Club and the Chicago Plan Commission hard to ensure that recommendations became realities. At the club's annual banquet in April, he announced that it had raised $20,000 to educate the public by means of lectures, widely circulated editions of the

Plan's contents, and other measures. Two weeks later the Chicago Plan Commission decided that it would use this money to "cover the town" with a publicity campaign of lantern slide talks delivered in multiple languages wherever an audience could be gathered, whether in churches, schools, theaters, assembly halls, or private residences. The commission's aim, as the

Chicago

Tribune

put it, was "to arouse interest in the efforts of the commission to make Chicago the 'most beautiful city in the world,'" and to "imbue every man, woman, and child with the spirit of cooperation." The paper soon gave Wacker space in its pages to argue for the value of the

Plan

directly.

Walter L. Moody, Commercial Ambassador Extraordinaire

What of the City?

|

Wacker's most important move, however, was to hire Walter L. Moody to lead the publicity campaign. Moody could have been the protagonist in a Sinclair Lewis novel. Well known in the Chicago business community as the general manager of the Chicago Association of Commerce, he was the author of

Men Who Sell Things,

published the year before the

Plan.

Moody's book was a guide to selling based on his twenty years of experience as a "commercial ambassador," his term for a salesman, whom he saw as a benevolent servant not only of his employers but also of the public at large. Moody was in his mid-thirties when he went to work for the Chicago Plan Commission in 1910, and by 1911 he was its managing director. Eight years later he described the task of "selling" the

Plan of Chicago

in another book, titled

What of the City?

This 430-page volume is part personal memoir and part history of city planning, though it is mainly a public relations instructional manual.

Moody begins

What of the City?

with the admission that he himself is neither architect nor engineer. His profession involves the "scientific promotion" of city planning, which he calls "in all its practical essentials . . . a work of promotion—salesmanship." And what does city planning require, above all? "M

oney,

" Moody explains, using small capitals for emphasis, continuing, "Without money no tangible results are possible." What did a city get in exchange for this investment? In four words, "civilization," "convenience," "health," and "beauty." To Moody, the foe of city planning in America was not active opposition but poor salesmanship. The key to success was to get the average citizen to pay serious attention to the issues and then "stir him to action when convinced." Moody believed that elected officials lacked sufficient focus to accomplish this, and so a group like the Chicago Plan Commission was required. While he expressed admiration for Burnham and Wacker as promoters, Moody understood better than they did that in a polyglot urban democracy, unlike Napoleon III's Paris, no plan could go forward simply by decree or just because the Commercial Club wanted it. The

Plan of Chicago

needed to be sold to Chicago at large by people like him, whom he characterized as salesmen not only of "civilization" but also of "harmony."

Chicago's Greatest Issue

|

Under Moody's direction, the commission embarked on a multidimensional promotional campaign. Moody, Wacker, and commission staff member Eugene Taylor became a de facto three-man lecture bureau. In the seven years after Moody was hired, they were indefatigable, presenting by Moody's calculation some five hundred talks to more than 150,000 listeners. They advertised their appearances with circulars and honed their standard spiel, winnowing the vast collection of lantern slides at their disposal to about two hundred images they used repeatedly. At the same time, Moody spread the gospel of planning through a number of publications. Of these, two were most important.

Chicago's Greatest Issue: An Official Plan

appeared in May 1911. This 93-page booklet was an inexpensively produced condensation of the

Plan of Chicago.

In

Chicago's Greatest Issue,

Moody ingeniously approached the

Plan

from the viewpoint not of the planners and their wealthy associates but of ordinary citizens, whom he called the "owners of the great corporation of Chicago." He led them step-by-step toward an understanding of why the

Plan of Chicago

was vital to their interests. He distributed

Chicago's Greatest Issue

for free to property holders and those who paid more than $25 a month in rent—that is, the Chicagoans whose support Moody thought most important in upcoming bond referendums.

Wacker's Manual of the Plan of Chicago

|

Moody prepared other booklets, including the enticingly titled

Chicago Can Get Fifty Million Dollars for Nothing!

(1916), which claimed that the figure named was the sum of the fees the city could collect by permitting dumping on the lakeshore plus the cash value of the land created by this fill. But his most impressive publication, in both conception and execution, was his

Wacker's Manual of the Plan of Chicago.

The first version of several editions of this book appeared in 1911. Like

Chicago's Greatest Issue,

Wacker's Manual

was a shorter and more economically produced version of the

Plan of Chicago,

though it was more substantial than

Chicago's Greatest Issue.

Moody negotiated the inclusion of

Wacker's Manual

in the public school eighth-grade civics curriculum. The school edition was complete with study questions and a teacher's manual. Adoption of the

Manual

by the schools was no doubt facilitated by the fact that Frank Bennett was vice president of both the Chicago Plan Commission and the Board of Education. Approximately seventy thousand copies were published and distributed by 1920.

Promoting the Promotion

|

Making

Wacker's Manual

a required textbook reflected Moody's belief that "the ultimate solution of all major problems of American cities lies in the education of our children to their responsibility as the future owners of our municipalities and the arbiters of their governmental destinies." The planners picked eighth graders, Moody explained, because students at this age were old enough to understand the issues but still young enough to be impressionable. Besides, many Chicago youth ended their education at this point, so it was the last chance to appeal to a large captive audience. Moody hoped, evidently with some success, that school children versed in the

Plan

would in turn educate their parents. He invited teachers and administrators to a banquet in their honor and asked for their advice on how

Wacker's Manual

might be improved.

Kudos and Critiques

Moody also deployed the most up-to-date medium of the time. Under his supervision, the Chicago Plan Commission produced a two-reel promotional film, titled

A Tale of One City,

which was shown in more than sixty theaters throughout the city. The premiere screening, in Moody's words, "packed the house to capacity" with an audience that "was as representative as a grand opera occasion." But Moody focused most of all on the print media. Magazines published dozens of articles on the

Plan

and the Chicago Plan Commission, almost all of them favorable. Some were written by Chicago Plan Commission and Commercial Club members, including Charles Hutchinson, Charles Dawes, and John Shedd. Former Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot, who had appointed Burnham to a committee advising the university on its physical plan, commented in the

Century,

"We here see in action democratic enlightened collectivism coming in to repair the damage caused by exaggerated democratic individualism."

Try as they might, Wacker and Moody could not guarantee that all the responses would be positive. Well before Moody was hired, numerous individuals, including some wealthy Chicagoans, raised one of the most persistent criticisms of the

Plan:

for all its environmentalist slant, it pays scant attention to housing or the day-to-day lives of working people. George E. Hooker of the

City Club,

writing in the

Survey

shortly after the

Plan of Chicago

was released, charged that in addition to failing to address housing, the

Plan

did not deal effectively with transportation in the heart of the city.

Conversion Experience

|

Some critiques were more pointed. John Fitzpatrick, president of the

Chicago Federation of Labor,

refused Mayor Busse's invitation to serve on the Chicago Plan Commission. Fitzpatrick complained that the commission's main purpose was to assist commercial and industrial interests, who were guilty of working their employees "long hours at starvation wages." Fitzpatrick continued, "I know something about the conditions that the workers in Chicago have to contend with, and when you talk about beautifying Chicago industrially and commercially and ignore the cry of despair among the men, women, and children whose only fault is that they must toil to live, [it] makes one hesitate and ask if we are in the era before Christ or in the twentieth century of Christianity."

One of the most detailed attacks on the

Plan

came in a series of articles in the

Public,

the Chicago-based periodical that called itself the "National Journal of Fundamental Democracy" and "A Weekly Narrative of History in the Making." Long suspicious of the motives of supposedly civic-minded businessmen, the

Public

stated in the first article, "The working masses of Chicago . . . have little use for the Commercial Club or any of its recommendations." The

Public

said that it would nevertheless try to evaluate the

Plan of Chicago

with an open mind. Be that as it may, in its next article on the subject, the magazine accused the planners of being anything but disinterested or munificent, since they would profit from the changes they proposed while Chicago's citizens footed the bills. The

Plan

in fact did not deal with issues that affected most people below the privileged class, the

Public

contended. In its March 7, 1913 issue, the magazine praised George Hooker's description of the Chicago Plan Commission as a group of boosters, not experts, who were all too willing to put corrupt aldermen like John Coughlin and Mike Kenna on key policy committees. It asserted that Chicago needed and deserved to have true experts do the planning. The members of the Commercial Club were, in a word, unqualified. "Probably no other large city in the world is so badly bedeviled as Chicago by grossly selfish interests masquerading as public benefactors," the

Public

claimed.

Requiem for a Planner

Will the Plan Be Carried Out?

|

Although such criticisms emerged, the early reception of the

Plan of Chicago

was overwhelmingly positive, which greatly pleased Daniel Burnham. While he continued to speak and write in favor of the

Plan's implementation, Burnham entrusted the burden of promotion to Wacker, Moody, and the members of the Commercial Club and the Chicago Plan Commission. He had already given more time and energy to remaking Chicago than anyone could reasonably ask, he still had his busy architectural firm to oversee, he enjoyed his European vacations, and he had accepted other posts. President Taft had appointed Burnham the first chairman of the new U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. Its work included advising on the proposed Lincoln Memorial at the west end of the Mall, which Burnham had helped redesign a decade earlier. By the time

The Plan of Chicago

appeared, Burnham's already uncertain health and his prodigious energy were in decline. Daniel Hudson Burnham died on June 1, 1912, in Heidelberg, Germany.

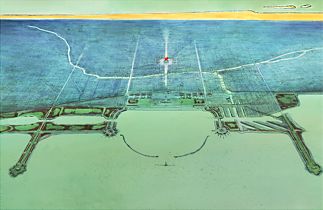

Final Resting Place

|

Word reached Chicago just before a performance by the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

at the North Shore (now

Ravinia

) Festival. Burnham was on the boards of both the orchestra and the festival. As a farewell salute, the orchestra added the funeral march from Wagner's

Die Götterdämmerung

to its scheduled program. Burnham was cremated and his ashes buried in

Graceland Cemetery.

Sixteen years earlier he had begun his planning of Chicago with a proposal to create a new lakefront recreation area by filling in the shoreline between Grant Park and Jackson Park. Almost immediately after his death, the successful campaign began to name this large stretch of man-made lakefront land

Burnham Park.

|