| Entries |

| S |

|

South Side

|

|

Chicago South Side has long had a distinct identity. Often identified in the second half of the twentieth century with the city's African American population, it has actually accommodated remarkable diversity.

The South Side boasts its own major league baseball team, the Chicago White Sox, and once provided a home to the Chicago American Giants of the Negro National Leagues and the Cardinals of the National Football League. It long has served as the location for much of the city's convention business, first with the Chicago Coliseum and the International Amphitheater, and later with the massive McCormick Place exhibition complex. The South Side has also provided a fertile site for creative energy, from the fiction of Upton Sinclair, James T. Farrell, and Richard Wright to the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks, the paintings of Archibald Motley, Jr., the sculpture of Lorado Taft and Henry Moore, the gospel music of Thomas A. Dorsey and Mahalia Jackson, the blues of Muddy Waters.

|

The late 1860s and 1870s also saw the movement of industry away from the Loop. In 1865 the Union Stock Yard opened in Lake Township, south and west of downtown Chicago. The Pullman Palace Car Company brought its plant and model city to Hyde Park Township in 1880. One year later Illinois Steel began operations at its massive South Works in South Chicago, also in Hyde Park Township. Chicago annexed both of these townships to the city in 1889, creating much of the South Side in the process.

Development was directly connected to transportation technologies and their expansion. The Illinois Central Railroad opened its first Hyde Park station at 51st and Lake Park Avenue in 1856. The expansion of horse-drawn streetcars and later cable cars (1880s) and electric trolleys (1890s) proved to be a boon to developers. From 1890 to 1892, the South Side “Alley L” began to make its way south from the Loop to Jackson Park in time for the World's Columbian Exposition (1893).

|

American-born, white, middle-class families also pushed south along the boulevards, populating large sections of the Near South Side, Douglas, and Grand Boulevard Community Areas. They were soon joined by other groups, especially middle-class Irish Roman Catholics and German Jews. The Irish founded the parish of St. James on 26th and Wabash Avenue in 1855. In 1889 the Christian Brothers established De La Salle Institute at 35th Street and Wabash Avenue in the Douglas Community Area. Among its graduates are five Chicago mayors.

German Jews also came to Douglas. In 1881 Michael Reese Hospital opened its doors at 29th Street and Cottage Grove. In 1889 the Standard Club, an elite Jewish men's organization, moved to 24th and Michigan Avenue. Kehilath Anshe Mayriv (KAM) Synagogue moved in 1890 to 33rd and Indiana Avenue.

Other European ethnic groups also made their way to the South Side. German Catholics and Protestants spread across the area. Working-class Irish communities appeared in Bridgeport, Canaryville, and Back of the Yards. After 1880, large numbers of Poles, Lithuanians, Czechs, Slovaks, East European Jews, and other immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe settled near the stockyards. These groups also followed the Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Scandinavians, and Germans to South Chicago and South Deering near the rapidly expanding steel mills and to other manufacturing centers.

South Side African American residents and institutions date back to the decades preceding the Civil War, although a concentrated settlement emerged only toward the end of the nineteenth century. More growth took place between World War I and the 1920s, when new employment opportunities in northern industry opened the doors for what came to be known as the Great Migration.

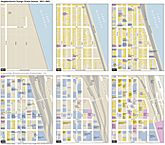

Residential segregation, rooted in nineteenth-century patterns, emerged in full force during the war era. With few exceptions, African Americans found themselves confined to a narrow strip south of the Loop between State Street on the east and Wentworth Avenue to the west. White residents moved farther south to Washington Park, Hyde Park, and South Shore. As population pressures increased, African American families pushed south of 39th Street (Pershing Road) toward Garfield Boulevard (5500 South) into Grand Boulevard and Washington Park, and east across State Street toward Cottage Grove. These predominantly white middle-class neighborhoods that included parts of the Douglas, Grand Boulevard, Oakland, Kenwood, and Hyde Park Community Areas resisted black residential encroachments. To the west of the Black Belt lay the predominantly white ethnic working-class neighborhoods of Bridgeport, Armour Square, Fuller Park, Canaryville, and Englewood. Here too blacks were not welcome.

As World War I came to a close, social, residential, political, and economic pressures reached a peak. In July 1919, a race riot broke out resulting in 38 deaths and hundreds of injuries. While rioting took place across the city, most of the injuries and deaths occurred on the South Side where the black and white Chicagoans lived and worked in close proximity.

|

The 1920s also saw the further dispersal of the population. White families made their way to the Southwest Side and to outlying parts of the South Side. Chicago's Bungalow Belt emerged, forming a wide ring around the city. These single-family free-standing structures modeled on Prairie School architecture were intimately tied to yet another transportation system, the private automobile. During the 1920s well-established ethnic groups, such as the Irish, Scandinavians, and Germans, pushed out of the older core neighborhoods to these newer middle-class and lower-middle-class developments. They were followed in turn by Poles, Lithuanians, and other Eastern and Southern Europeans.

In Back of the Yards, Bridgeport, and South Chicago, the Polish and other East European ethnic communities developed a wide range of social, cultural, and economic institutions including parishes, parochial schools, fraternal organizations, banks, savings and loans, and other businesses. By the end of the 1920s these European ethnic groups were joined, particularly in South Chicago and Back of the Yards, by Mexican immigrants.

|

Older South Side neighborhoods, especially the traditional Black Belt, also saw new housing in the 20 years after 1945. This housing was for the most part public housing built and administered by the Chicago Housing Authority. Dearborn Homes, Stateway Gardens, and Robert Taylor Homes replaced much of Federal Street. The new campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT ), designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, replaced another part of the old Federal Street slum. Private housing developments also appeared as Prairie Shores and Lake Meadows were constructed in the 1960s along the lakefront south of 26th Street. New and restored housing also appeared in Hyde Park, Kenwood, and Beverly. Urban renewal took various forms, but the South Side's landscape was most dramatically affected by public housing; institutional expansion in the form of IIT, the University of Chicago, and various hospitals; and the construction of the Dan Ryan and Stevenson Expressways. The new South Side, however remained very familiar to Chicagoans, as it retained its segregated housing patterns and huge pockets of poverty and wealth.

|

The South Side, however, has continued to attract investment. By the 1990s over a hundred firms had located at the site of the old Union Stock Yard. This industrial park is the most successful in Chicago even though employment levels remain well below those of the meatpacking industry at its height. A variety of neighborhoods have provided sites for new upscale housing, including Dearborn Park (which has expanded from the South Loop south of Roosevelt Road), Central Station (along the lakefront south of Roosevelt Road), Bridgeport, Hyde Park, Kenwood, the Gap, and Chatham. Chinatown has spread beyond its earlier boundary along Archer Avenue with the development of Chinatown Square. In 1991 the Chicago White Sox began to play in a new Comiskey Park across the street from the old stadium. With its neighborhoods, parks, museums, and universities, the South Side continues to play an important role in the social, cultural, political, and economic life of the city.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.