| The Plan of Chicago |

| Chicago in 1909 |

| Planning Before the Plan |

| Antecedents and Inspirations |

| The City the Planners Saw |

| The Plan of Chicago |

| The Plan Comes Together |

| Creating the Plan |

| Reading the Plan |

| A Living Document |

| Promotion |

| Implementation |

| Heritage |

|

Historian of architecture Kristen Schaffer has conducted the most careful examination of the Plan of Chicago ' s authorship, and she has published some of her findings in her introduction to the Princeton Architectural Press 1993 facsimile edition. While Schaffer sees the final version of the Plan as reflecting the collective effort behind it, she maintains that the published version unquestionably bears the mark of Burnham's “genius.” This “genius,” she explains, “lies in his vision and his energy, in his ability to see how all the elements of the city and its functioning are related and his tenacity in making others see it as well.” Schaffer's view squares with that of Charles Moore. In his biography of Burnham, Moore says of the Plan, “The text, prepared from comprehensive notes made by [Burnham], is replete with his striking phrases, his happy characterizations, and is imbued with his settled philosophy: that the chief end of life is service to mankind in making life better and richer for every citizen.”

Despite his warm praise, Moore perhaps shortchanges Burnham somewhat in describing the draft, which consists of about three hundred handwritten pages, as “comprehensive notes.” (The draft is part of the Daniel H. Burnham Collection in the Archives of the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago. ) As Schaffer describes it, the first half of this manuscript is the basis of many major elements of the final version of the Plan. Schaffer characterizes the second half of the manuscript as a more “technical” discussion of “the provision of services,” such as utilities, education, and hospitals.

Comparing the draft not only with the published version but also with many other documents produced in the planning process, Schaffer reaches several noteworthy conclusions. Some of Burnham's “technical discussion” finds its way into the Plan in altered form, as what Schaffer calls “small asides.” Schaffer states that a 1908 report prepared by the Committee on Interurban Roadways is the major source for the Plan's discussion of that topic in chapter 3, while the section of chapter 7 on Michigan Avenue derives from the booklet on the subject by the Committee on Streets and Boulevards that was published before the Plan appeared. Elsewhere Schaffer offers evidence that in writing his draft Burnham integrated material provided by Bennett, and that Moore borrowed from Burnham's speeches and addresses as part of the editing process.

Schaffer finds intriguing those sections of the Burnham manuscript that are “entirely omitted from the final version, or so reduced as to be effectively nullified.” She persuasively argues that they “show a very different side of Burnham and challenge conventionally held assessments of the Plan ” as socially conservative and apparently little concerned with the needs of ordinary citizens. The omitted sections, she contends, reveal a Burnham who believed more fully than the Plan would suggest in the need for the city government to take an active role in improving the living and working conditions of the mass of Chicagoans. Burnham also speaks in a way that the Plan does not of the importance of the government making sure that public utilities serve the community responsibly. He similarly urges the authorities to see that hospitals do a better job of reducing human suffering, and that medical research benefits the common good, not private medical schools and their staffs.

|

A brief look at the archival material offers additional insights into the evolution of the Plan from draft report to published volume. Moore began his work by preparing an outline that he changed considerably as he proceeded toward the printed version. Chapter 1 in the outline does not include the narrative of how the Plan came to be written that appears in print. The outline also culminates with the intriguing topic, “The City developing a soul.” While the Plan talks about a city having other human qualities, including “spirit,” “soul” is not one of them. More significantly, Moore changed the order of the presentation of topics, and he trimmed the historical background.

|

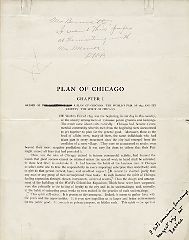

Burnham certainly does not seem to have simply handed the manuscript off to Moore and then stepped away. He edited his editor. On the top of a galley of the opening page is a handwritten note from Burnham to Bennett, which reads, “Mr. Bennett: I want this paper at the meeting with Mr. Moore. DHB.” Someone, presumably Burnham, suggested changes in the chapter title, which was further altered before publication. On the bottom right of the page is a notation for the printer in Moore's handwriting. All of these are indications of a complex collaboration.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.