|

Architecture

has always loomed large in accounts of Chicago. Famous architects like William Le Baron Jenney, Daniel Burnham, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill are firmly embedded in local history and lore, as are buildings celebrated in architectural history like the Monadnock, Rookery,

Auditorium Building,

Robie House, and Sears Tower. The particular kind of fascination with architecture seen in Chicago suggests certain characteristic attitudes. Whereas in older European and American cities the major monuments are often palaces, governmental buildings, and great cathedrals, Chicago's monuments have more often than not been business buildings, houses,

schools

and churches. In its concentration on these landmarks of daily use, the city seems to celebrate its democratic, mercantile, and middle-class character. The creation of a comfortable built environment for a very large portion of the population, more than any individual buildings, no matter how successful, stands as the Chicago area's crowning architectural achievement.

From the Founding to the Fire

St. Mary's Catholic Church

|

For the great city of Chicago to rise from its marshy site a number of important infrastructure works were necessary. In the years before the Great Fire the most important were the construction of the

Illinois & Michigan Canal

between 1836 and 1848, the

water

system designed by engineer Ellis Chesbrough in the 1860s, and the city's great

railroad

system. Despite these impressive works, however, the city itself during most of the mid-nineteenth century would have looked to most observers little different from many other young and fast-growing Midwestern cities. Small, mostly wood, buildings straggled alongside unpaved roads that were alternately dusty and muddy. Even the most conspicuous structures in the city were relatively small and unimpressive by the standards of larger Midwestern cities like St. Louis, not to mention those of Eastern cities and the European capitals. It was not until the last years before the fire that great commercial emporia like Marshall Field and hotels like the Palmer House rising on State Street gave Chicago buildings to rival those in more established places.

Survey Map of Chicago, 1834

|

From a small gridiron plat around the meeting of the south and north forks of the

Chicago River,

the city bounded outward by annexing adjacent development, virtually all of it laid out in conformity with the original plat and the regular mile-square grid pattern of the American land survey specified by Congress in 1785. The relatively low density of Chicago's residential neighborhoods and the high percentage of single-family detached homes rather than the tightly packed tenements and row houses of cities in the eastern United States and Europe was in part the result of a new construction technique, the

balloon frame.

Although this technique, in which the use of

lumber

in standardized sizes and machine-cut nails made possible rapid and inexpensive construction, has sometimes been claimed as a Chicago invention, this claim is dubious. Not only do the origins of the balloon frame appear to go back well before the founding of Chicago, but it was also only one step in a long process of substituting prefabrication for handwork. Whatever its origin, the balloon frame undoubtedly helped make possible, during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, a

construction

boom in Chicago unmatched by any city up to that date. By the time of the Great Fire a large part of the population, including many factory workers, could afford what was then the extraordinary luxury of a single-family detached home, often a small one-story or story-and-a-half frame or brick house known as a workman's cottage. Entire neighborhoods of these cottages were erected on all sides of the central business district. Many can still be seen today in close-in neighborhoods like

Bridgeport

on the

South Side

or

Old Town

on the North Side.

Railway Map, 1879

|

Another reason the city could grow so quickly and at densities so much lower than older cities was that Chicago grew up with

public transportation.

During the years before the fire, the horse-drawn

street railway

and the cable car allowed a vast expansion of the settled area. The advent of the steam railroad permitted suburban settlements well beyond the continuously developed urban fabric. Many of these railroad suburbs were upper-middle-class enclaves.

Riverside,

designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux with large lots, carefully planned curving streets, and generous public open spaces, was the most famous early American suburb in the picturesque mode. Other outlying communities, like

Blue Island,

were industrial, accommodating factories and working-class housing. By the time of the Great Fire, suburbs radiated outward from the central city along the railroad lines like beads on a necklace.

From the Fire to the First World War

Aftermath of Great Chicago Fire, 1871

|

The Great

Fire of 1871

wiped out much of the central area of Chicago. Because much of the

infrastructure

and industrial capacity of the city had already decentralized, this disaster did not destroy the city's production capacity. Moreover, with the aid of insurance money and investment funds drawn primarily from Eastern cities, the city rebuilt rapidly. Despite new laws enacted to guard against the worst fire hazards, the immediate post-fire rebuilding tended to reproduce the pre-fire configurations.

Sanitary-Ship Canal Album, 1892-1900

|

In the years between the Great Fire and the First World War, Chicago became a great industrial power and had its period of greatest sustained growth. It captured the imagination of individuals around the world as the “shock city” of its day, the place where people came to see the emerging metropolis of the future. This growth was made possible in part by a vast expansion in basic infrastructure. Perhaps the most striking improvement was a massive program to remove the health hazards caused by dumping untreated sewage into the lake, which was where Chicago got its fresh

water supply.

The solution, finally completed at the turn of the century after monumental engineering work directed by the newly formed Sanitary District of Chicago, was to reverse the flow of the

Chicago

and

Calumet Rivers.

Another major public undertaking was the creation, by the federal government, of a major port at Lake Calumet by dredging that started at the end of the 1860s. Finally, there was the extension of the

transportation

system and the appearance of the electric streetcar and then, starting in the early 1890s, the elevated

rapid transit

train.

Rookery Building, c. 1888

|

The most striking physical manifestation of the city's modernity was seen in the

Loop,

the central business district named originally for a circuit of cable car lines that encircled it and reinforced, after 1897, by the Loop elevated. Here, starting in the 1880s, a group of buildings burst through the four- to five-story plateau that had marked the upper limit of practical commercial construction until that time. Promptly dubbed

skyscrapers,

these new buildings had become practical with the advent of the passenger elevator, new methods of foundations and fireproofing, and other technological advances. Skyscrapers had actually appeared in New York in the 1870s, a decade earlier than in Chicago, but because Chicago's business district was smaller and the pace of construction greater in the 1880s, it was along broad, regular streets like Dearborn and LaSalle in Chicago's Loop where these buildings found their most striking and characteristic expression as a cliff of large, rectangular structures with relatively little ornament but enormous plate glass windows. Although they were a source of civic pride, their enormous scale and fears about their safety also inspired intense hostility. This novel cityscape attracted worldwide attention and comment.

These office buildings, lofts, and retail buildings were the work of a large number of urban professionals, including developers like the Brooks brothers of Boston, agents like Owen Aldis, architects like William Le Baron Jenney, Burnham & Root, Holabird & Roche, and Adler & Sullivan, engineers like Charles Strobel, William Sooy Smith, and Corydon T. Purdy, and contractors like George A. Fuller, who developed the first large-scale general contracting firm in the country. All of these men played major roles in the creation of the first buildings with complete metal skeletons and relatively thin exterior claddings, a system that finally came of age about 1890.

Aerial: Union Stock Yard, 1936

|

As land prices rose in the business district, activities that required large amounts of inexpensive space tended to move further afield. This led to the creation, among other industrial areas, of the Chicago

Union Stock Yard

starting in the 1860s, the company town of

Pullman

in the 1880s, and the Central Manufacturing District, perhaps the country's first planned industrial district, at the turn of the century.

Samuel Gross's Subdivision

|

Explosive growth also brought congestion, noise, and pollution. This led, in turn, to a constant outward movement of families searching for greener, less congested living environments. In this process of dispersal the city's residential areas came to be marked by an increasing segregation and contrast between rich and poor neighborhoods, ranging from the slums and tenement areas close to the Loop to the mansions of the

Gold Coast,

relocated in the late nineteenth century from just south of the business district to north of the Loop. Both poor and affluent areas were relatively small in area, though, compared to the large working- and middle-class

subdivisions

that pushed outward in all directions. During these years residential developers, led by Samuel E. Gross, perhaps the country's largest, transformed the housing industry by building large numbers of units and entire subdivisions at a time. Single-family houses were interspersed with the city's characteristic two-flat and three-flat

apartment

buildings as well as, in affluent areas, the newly fashionable “French flats,” or apartment buildings for the affluent.

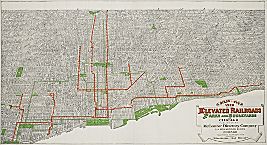

Map of Elevated Railroads/Parks, 1910

|

Complementing the new residences were the neighborhood

schools,

churches, and other community buildings as well as miles of retail frontage along arterial streets, particularly the major diagonal roads and the large streets that ran along the mile-square grid lines. Also complementing the residential subdivisions was a major system of parks and boulevards, projected in the late 1860s but not finished for several decades, that encircled the built-up portion of the city from

Jackson Park

in the south to

Lincoln Park

in the north. This system was in part a sanitary effort, offering what citizens of the time thought of as reservoirs of light and air in a congested and polluted city and in part a means to enhance the

real-estate

value of adjacent property.

Illinois Steel Works, Joliet, 1880-1901

|

The same diversity marked the railroad suburbs beyond the city limits. At the upper end of the scale were elegant places like

Evanston

and

Kenilworth

on the North Shore. The most affordable included some of the suburbs to the south like

Dolton

or

East Chicago

in Indiana. In the middle range, on all sides of the city, were the vast majority of suburban communities. Beyond the suburbs, booming satellite industrial cities like

Joliet,

Aurora,

Waukegan,

and

Gary,

Indiana, each had a business center and outlying districts as well as a range of economic activities, income levels, and building types similar to those of Chicago itself but on a reduced scale.

Court of Honor, 1893

|

This period also saw the first efforts at systematic city planning. The White City, the

World's Columbian Exposition

of 1893, with its coordinated planning and clean white architecture, marked a strong contrast with the often chaotic gray city to the north. It became a model for subsequent planning efforts and a major inspiration for the famous 1909

Plan of Chicago

by Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett and many subsequent

plans

across the Chicago area and the nation. Although most of the ideas espoused in the plan had been formulated by others in the years prior to its publication, and although only a few of its provisions were actually executed, this plan quickly became the country's most famous urban planning document and has exerted a hold on the imagination of Chicagoans ever since.

Between the Wars

Municipal Airport, 1929

|

Between the world wars, particularly during the boom years of the 1920s, a continued increase in density of

land use

in and around the Loop was accompanied by a continued outward push of residential development at ever lower densities at the perimeter. This pattern was possible because increased affluence had led to greater personal mobility, particularly after a dramatic increase in the 1920s in car ownership and the construction of new and better roads. By the onset of

World War II

an entire

expressway

system for the metropolitan area had been planned, and a stretch of Lake Shore Drive with limited access and cloverleafs, one of the earliest such installations in the country, had already been constructed. Another key piece of infrastructure of these years was Municipal (later

Midway

) airport, which opened in 1927 and soon became the nation's busiest.

Within the Loop a new generation of sleek new high buildings, often with towers made possible by the provisions of the 1923

zoning

ordinance, dominated the skyline. The completion of a

bridge

over the Chicago River at the north end of Michigan Avenue and its continuation as a great commercial boulevard made possible a new retail district north of the river that would eventually eclipse State Street as Chicago's most important center for upscale

shopping.

Bungalow, 1922

|

The increasing affluence of the 1920s also allowed for a vast expansion in

residential development.

Within the city and inner suburbs a large number of solid but modest structures known as “Chicago bungalows,” really an updated version of the worker's cottage, created a broad band on all sides of the city center and extending outward to suburbs like

Berwyn,

which had a particularly spectacular collection of these houses. Another important development was the growth of apartment districts in places like

Uptown,

Rogers Park,

Hyde Park,

and

South Shore,

where railroad and rapid transit lines provided easy acess to downtown. With the rapid development of new residential districts and the increasing use of the automobile came the growth of regional shopping and business centers, the most notable located at the elevated stations at Englewood on the South Side and

Uptown

on the North Side. These became miniature versions of downtown with their own

department stores,

specialty shops,

movie theaters,

and other urban services. Development further out grew even more quickly, with new subdivisions around existing railroad suburbs and entirely new communities in areas opened up by the automobile. As in previous eras, these suburbs ranged from elegant upper-income places to working-class suburbs and industrial satellites.

The Postwar Decades

Route 83, 1974

|

After the Second World War most of the building patterns already established in the 1920s resumed but on a larger scale. The long boom of the postwar decades included tremendous investment in infrastructure, particularly for automobile and air travel. Construction of the region's

expressway

system, projected in the 1930s, started in earnest after the war with local funding but was greatly accelerated by the federal funds available through the Interstate Highway Act of 1956. At the same time, the area's public transportation system, temporarily buoyed by ridership increases during World War II, continued a long decline. The

Chicago Transit Authority,

created in 1947 to take over private transit operations, first required a subsidy in 1970 and has, since then, seen round after round of subsidy hikes and ridership declines. Along with a rise in automobile travel came an enormous increase in air travel, particularly with the development of the commercial

airline

and the creation of a new airport,

O'Hare

Field, which soon took over from Midway the title of the nation's busiest.

Despite the apparent vigor of the region, there was considerable concern about the future. Chicago's industrial plant had not been updated sufficiently during the long years of the

Great Depression

and war to keep pace with developments in the Sun Belt and elsewhere. Much of the central business district was old and congested. Beyond the Loop were square miles of industrial and residential land that were considered obsolete and blighted. Civic and government leaders hoped to counter these problems with new planning techniques and an aggressive program of

urban renewal.

Rendering for Sears Tower, 1971

|

In the Loop itself, after a relatively short postwar lull, a building boom in the late 1950s through the 1960s that rivaled those of the 1880s and 1920s was initiated largely by private real-estate interests. The new structures included some of the largest and tallest office buildings in the world, notably Sears Tower and the John Hancock Building, both by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Chicago's most successful postwar corporate architecture firm. Other major undertakings in the central business district included a large planned development at Illinois Center, an enormous convention center complex at McCormick Place along the lakefront to the south of the Loop, and, to the north along Michigan Avenue, the creation of elaborate mixed-use complexes, starting with Water Tower Place in the early 1970s.

Sandburg Village, 1964

|

The prognosis for residential areas around the Loop, however, was less bright. Here postwar planners saw mostly older houses, decay, and blight. They initiated aggressive urban renewal programs that resulted in the demolition and rebuilding of large areas, including, for example, most of the

Near South Side.

In the place of the demolished structures rose new houses and apartment buildings such as Prairie Shores and Lake Meadows, institutional structures like a new

Michael Reese Hospital,

and a new campus for the

Illinois Institute of Technology.

In some cases, like the townhouses in Hyde Park on the South Side and the apartments of

Sandburg Village

on the North Side, the planners' intentions of stabilizing neighborhoods and retaining middle-income residents in the city were at least partially realized. On the other hand, the creation of massive

public housing

projects, particularly the high-rise apartment buildings of the

Robert Taylor Homes

on the South Side and the

Cabrini-Green

complex on the North Side, proved to be highly problematic.

Many of the most successful developments seemed to have had nothing to do with planning. Many older, apparently decaying neighborhoods near the center that were spared demolition from urban renewal bounced back as middle- and upper-middle-class communities through a process of private restoration and

gentrification.

This change coincided, however, with a continuous loss of jobs and income in many neighborhoods further out. Large parts of the South and West Sides, particularly, were hard hit as high-paying industrial jobs disappeared, and racial and ethnic change created instability.

Levitt Subdivision in Buffalo Grove, 1968

|

While city population declined after World War II, suburban development boomed. At one end of the spectrum were places like

Barrington Hills

to the northwest and

Oak Brook

to the west. Here substantial houses occupied lots that often exceeded an acre in size. At the other end of the scale was

Park Forest,

a planned community developed immediately after the war in the far south suburbs that contained a mix of small ranch houses (the postwar equivalent to the interwar bungalows) and garden apartments as well as a shopping center and a wide variety of community structures. This attempt to completely master plan a community, while widely hailed and intensively studied, never became typical. Instead most development proceeded as it had in the past, with a patchwork of residential subdivisions and industrial and retail development all done by private interests and schools, parks, and public buildings put in place by local governments. The vast majority of suburban development was based on subdivisions of middle-class ranch houses and split-levels with four to eight houses per acre, for example, in

Morton Grove

and

Niles

to the north or

Franklin Park

and

Melrose Park

to the west.

Woodfield Mall Interior, 1973

|

With the residential growth came major new business developments. Industrial concerns continued their push out from the center to the periphery, occupying newly created complexes for themselves or quarters in planned industrial parks. Located just west of O'Hare Airport, for example, the Centex Industrial Park was the largest of its kind in the country. Along with the industrial parks came office parks and

shopping districts,

such as a trio of pioneering open-air centers in the 1950s, including River Oaks in the south suburbs,

Oak Brook

in the west suburbs, and

Old Orchard

in the north suburbs.

Since the 1970s

In recent decades renewal at the core has proceeded at the same time as continued outward growth. Despite all of the fears, particularly during the dark years of industrial decline and civil unrest in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Chicago's central area did not collapse. An increase in the number of jobs in the Loop devoted to high-level corporate, financial, and legal business as well as a growing economy based on

tourism

and culture led to a massive office building boom starting in the 1980s. The central area also saw an increasing residential population, with the conversion of loft and office buildings like those in the

Printer's Row

area just south of the Loop, the construction of large new apartment buildings such as Presidential Towers just west of the Loop, and the development of entire new residential neighborhoods like the one at

Dearborn Park

just south of the Loop. Meanwhile, gentrification spread from a small nucleus in Old Town on the Near North Side to include very substantial areas of the North and Northwest Sides. By 2000, new building and rehabilitation were evident even in some of the most depressed areas of the West and South Sides, giving reason for some optimism despite continuing high rates of poverty and crime in many neighborhoods in the city and growing problems in some of the inner-ring suburbs and elsewhere in the area.

Deep Tunnel System, 2003 (Map)

|

Despite the stabilization and revitalization of the core, the majority of growth in the metropolitan area has continued to take place at the periphery. In some key areas important new infrastructure has been constructed. Some of the area's most difficult problems of flooding and wastewater treatment were addressed by new wastewater treatment facilities and the massive Tunnel and Reservoir Project (TARP, more commonly known as the

Deep Tunnel

), which stores water after heavy rains until wastewater treatment plants have the capacity to treat it. The transportation infrastructure, on the other hand, has not kept up with demand. Although automobile ownership and use has continued to increase, relatively few new highways have been built, and public transit has not managed to maintain, let alone increase, its share of trips areawide. The result has been increasing congestion. Much the same problem plagues the city's airports. Even with massive rebuildings at O'Hare and Midway, the region's air traffic system has become increasingly inadequate, threatening the region's economic vitality and quality of life.

Despite well-meaning regional plans, most of the development in the area has been due to private initiative more than public planning, which is largely local and often quite piecemeal. By 2000, new suburban residential developments had pushed to the east along

Lake Michigan

toward the Michigan border, to the south toward Kankakee, to the west well past the

Fox River,

and to the north deep into southern Wisconsin. House sizes at all economic levels have increased, although lot sizes have declined and increasingly large numbers of rental apartments and row houses have started to appear in the suburbs.

Along with the residential developments have come new shopping centers, strip malls, discount centers, and other retail establishments. Office, business, and industrial parks, like the Meridian Business Park in

Aurora,

have grown in size and sophistication. The most spectacular phenomenon of the last several decades has been the rise of large outlying business centers. The most important is located at

Schaumburg,

surrounding the Woodfield Mall, an enclosed shopping center that was the largest in the country at the time of its completion in 1971. Around the mall has grown a large collection of office, retail, and

hotel

buildings that at the opening of the twenty-first century constituted the largest business district in Illinois outside of Chicago's Loop. Together with other business centers like the master-planned center at Oak Brook and the largely unplanned centers near O'Hare airport and

Rosemont,

these business districts have helped create what is effectively a multinucleated structure for the metropolitan area.

One of the most remarkable aspects of this outward expansion since the 1920s has been the relatively slow growth in population but large increase in occupied land. For an increasing number of critics this constitutes “sprawl,” an undesirable, uncoordinated, and wasteful development pattern. The decline in density has actually slowed since World War II, however, and

environmental

problems, while significant and troubling, are perhaps less worrisome, at least at the local level, than they were in the past. It is perhaps more useful to consider recent developments, like the history of Chicago's development from the beginning, as an apparently hasty, unplanned, and chaotic process that, nevertheless, has actually been marked by a great deal of internal order and can be seen as the logical result of a vast increase in wealth, mobility, and choice by a very large number of Chicagoans.

Robert Bruegmann

|