| Entries |

| M |

|

Metropolitan Growth

|

|

|

Chicago's explosive growth during industrialization has shaped metropolitan development down to the present. Factories located across the area, taking advantage of the many transportation lines. Chicago's opportunities drew hundreds of thousands of newcomers from the great waves of European emigrants in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. African American migrants from the South were drawn to Chicago between the 1910s and 1960s, and in the late twentieth century immigrants from around the world continued to take advantage of regional economic opportunities. Ethnic and racial diversity both resulted from metropolitan growth and contributed to its expansion.

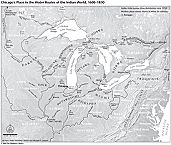

While humans have inhabited this area for thousands of years, most of our local history begins with the Potawatomi presence in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Potawatomi farmed, hunted, and traded in this area, locating along trails and water routes. Algonquin is alongside a Potawatomi trail between the Chicago River and Lake Geneva. Summit and Portage Park are among the sites that served as portage between rivers—here between the Chicago and Des Plaines rivers. Lisle, St. Charles, Thornton, Skokie, Palos Hills, and Oak Brook all have evidence of Potawatomi settlements along rivers within their current boundaries.

|

German farmers came to dominate whole communities in northeastern Illinois by the 1840s. They composed an important part of early Bloomingdale, Arlington Heights, Calumet City, Clearing, Carol Stream, Edison Park, Skokie, Dolton, Lincoln Park, Northbrook, Niles, Edgewater, Harvard, and Hoffman Estates. These Germans quickly established institutions—particularly churches and schools—which helped them to maintain their traditions. Within a few years after the Civil War, Niles Center (Skokie) had both German Lutheran and German Catholic congregations. German settlers founded both Elmhurst College and North Central College in the mid-nineteenth century.

|

Railroad settlements also shipped the raw materials of city building into Chicago. Bricks from Northbrook, North Center, Park Ridge, Roselle, West Lawn, Dolton, and West Ridge, as well as limestone from Naperville and Elmhurst, were shipped into Chicago along the railroad, especially after the Fire of 1871. Ice harvesting relied on railroads to carry ice to Chicago from Round Lake, Antioch, Crystal Lake, and Lake Villa.

|

Heavy industries also located along the railroad lines. Rolling mills on the Near North and Southwest Sides gave way to larger plants built at some distance from the city center, in areas like Hegewisch, Harvey, and South Deering which had access to multiple rail lines. Waukegan, Elgin, Aurora, Joliet, and Gary were labeled “satellite cities” by the turn of the nineteenth century and grew as industrial centers. The massive Pullman Company operations in Pullman, along the Illinois Central Railroad; the Hawthorne Works of General Electric, located in Cicero; Inland Steel in East Chicago; and the South Works on the East Side all took advantage of easy rail and water transportation to obtain raw materials and ship finished products.

|

Leisure opportunities drew these workers from the suburb or neighborhood where they lived and worked. Sunday excursions to ballparks, cemeteries, picnic groves, and music halls were hallmarks of nineteenth-century Chicago.

Picnic groves, with hiking, biking, and dancing, developed along rail and interurban lines. In West Garfield Park, picnic groves, a bicycle track, a horse race track, and greenhouses drew visitors from around the metropolitan area. Further from the city center, railroad excursions took Chicagoans to the Des Plaines River at Schiller Park, Wheeling, and Des Plaines. Dancing pavilions, picnicking, and camping attracted thousands during warm weather.

|

These resort sites each catered to different economic, and often different ethnic, clienteles. Wealthy Chicagoans were drawn to Lake Geneva and estate sites in DuPage, Lake, and McHenry Counties. In contrast, the picnic groves and cottages along Bangs Lake drew blue-collar Chicagoans to Wauconda in the early twentieth century. Robert Ilg built a recreational park along a streetcar line in Niles for his workers that included two outdoor swimming pools and a replica of the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Illinois Bell and Montgomery Ward both established vacation enclaves for employees in rural Warrenville.

|

In the years after the Civil War, commuters, who often worked in professional and managerial positions in the Loop, found new and existing railroad settlements attractive as home sites. Unlike their working-class counterparts, these upper-middle-class Chicagoans had the money and time to commute to work.

Developers in railroad towns subdivided property and usually graded streets and paved sidewalks. Sometimes they began the process of providing other services (water, sewers, gas, and then electricity) to attract their affluent clientele. These suburban subdivisions were both inside and beyond the current Chicago city limits: Riverside, Morgan Park, Kenilworth, Elmhurst, Irving Park, Austin, Park Ridge, Beverly, Norwood Park, Rogers Park, Wilmette, La Grange, Western Springs, and Homewood.

|

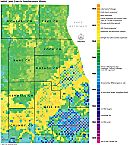

By the 1920s, bungalows provided a housing alternative to cottages for successful working-class Chicagoans who like their wealthier counterparts sought suburban living both within and outside the city. Portage Park, Hermosa, Chatham, Brookfield, West Elsdon, Gage Park, and West Ridge grew after World War I, providing new housing in outlying districts for less affluent Chicagoans.

Settlements interspersed on the agricultural landscape dotted the Chicago metropolitan landscape in the early twentieth century. A variety of attractions, including jobs, picnics, and homes, drew individual Chicagoans to these areas. Railroads, distinctive physical amenities, and industrial sites helped to determine the locations of these communities. But other factors could also affect where settlements emerged and flourished, including temperance and government services.

Suburban government developed to meet the needs of geographically isolated settlements along railroad and streetcar lines. In the nineteenth century, suburban governments initially provided basic infrastructure services demanded by residents of railroad suburbs, such as running water and sewers. Over time, each suburban area developed a specific packages of services (and taxes) which attracted residents from the metropolitan area who sought those public benefits and the same level of taxation. Communities with the wealthiest residents had the broadest range of services and taxation.

Temperance also was a factor in the establishment of nineteenth-century municipalities. Prohibition of liquor drew like-minded residents to an area. It kept out taverns and restaurants that served liquor—establishments that might cater to people well beyond the confines of the immediate area. Temperance was also related to ethnicity and religion, as many Roman Catholic immigrants, for example, looked askance at prohibiting alcohol. South Holland, Barrington, and Palatine were among the farming communities that incorporated in the mid-nineteenth century at least in part to restrict the sale and consumption of liquor.

|

|

While much of the differentiation and sorting which took place among settlements across the metropolitan area provided more choices for residents, these same sorts of processes were used to keep whole classes of Chicagoland residents from portions of the metropolitan area. Expensive homes and property in exclusive subdivisions made a number of suburbs affluent bastions. While Chicagoans of more modest means could choose a less expensive area, wealth brought the widest range of choices. Kenilworth's developer intentionally drew residents from affluent city neighborhoods like Prairie Avenue. Golf, along a northwestern railroad line, used incorporation to protect a very small upper-middle-class area of half-acre lots.

|

|

Highways and later expressways, overlaid on thenineteenth-century system of railroads and streetcars, shaped the course of twentieth-century development. Agriculture, industry, homes, and leisure were all affected by these changes. The existence of a paved road (and later a limited-access highway) gave new locations advantage, especially in the post–World War II economy.

From the end of World War I to the development of the interstate expressway system after 1956, state and county highway departments surfaced roads and opened new connections across the metropolitan area. The paving of Ogden and North Avenues westward from Chicago out through DuPage provided ready automobile access to areas that had remained quite rural. Lincoln Highway connected isolated communities across the southern part of the metropolitan area.

|

|

In contrast to the private development of railroads and streetcars, funding for the interstate system came from the federal government and was administered by the state highway department. Federal influence on the growth of the Chicago metropolitan area extended beyond the interstates. By the 1950s, federal insurance for homebuilding helped to boom outlying growth. Garfield Ridge, Harwood Heights, Flossmoor, Lombard, Schiller Park, Morton Grove, Des Plaines, Park Ridge, Park Forest, and other areas grew dramatically as more and more Chicagoans could afford homes. The federal government's involvement made it more economical for many Chicagoans to purchase a home rather than rent. Coupled with the homeowner's deduction on income taxes, the insurance program underwrote the postwar development boom in suburban living.

|

At the same time that federal home loan insurance programs were booming suburban areas, other federal dollars came to Chicago for urban renewal and public housing projects. Whole sections of the Near North Side, Near South Side, Near West Side, the Loop, Douglas, Grand Boulevard, and East Garfield Park were razed and redeveloped using over $150 billion in federal urban renewal funds. Despite the lower costs of building public housing on less expensive land in outlying areas and suburbs, the politically expedient decision was made to build most public housing in the metropolitan area on urban renewal land in a ring around downtown Chicago.

|

Deindustrialization had a less detrimental effect on areas which were able to develop their local economies in new directions. When the Kroehler Furniture Factory, which had been Naperville's largest employer for nearly a century, closed in the mid-1970s, it did not signal the decline of the community. Positioned to take advantage of new metropolitan growth along interstate highway corridors, Naperville moved successfully into service and light industry.

|

These new suburban developments have drawn white-collar workers out from the Loop. Unlike in the nineteenth century, when whitecollar workers commuted from suburban homes into the Loop, workers in the twenty-first century often commute from suburb to suburb. The dispersal of work locations has left white-collar workers increasingly reliant on automobile travel, in contrast to the railroad commutation of the nineteenth century. Their working-class counterparts, who in the nineteenth century lived near their industrial jobs, have also joined the ranks of commuters. High commuting costs, both in time and money,are especially challenging for low-paid workers.

In the last three decades, a new wave of immigration has also affected metropolitan development. Both highly educated, high-skilled professionals and low-skilled, poorly educated workers are part of this new immigration. Immigrants from Asia and Latin America have settled across the metropolitan area, reshaping the landscape differently from earlier immigrants and migrants, but no less dramatically.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.