| Entries |

| S |

|

Saloons

|

|

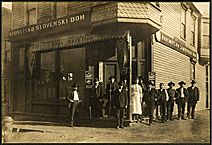

The rapidly growing ethnic population swelled the saloon ranks through the mid-nineteenth century, but during the early 1880s a growing overcapacity in the brewery industry began to force change. Overestimates of future growth, along with easy rail access to Chicago for St. Louis and Milwaukee brewers, left all of the producers scrambling for retail outlets. The answer lay in an adaptation of the British “tied-house” system of control. Brewers purchased hundreds of storefronts, especially on the highly desired corner locations, which they rented to prospective saloonkeepers, along with all furnishings and such recreational equipment as billiard tables and bowling alleys. Schlitz and a few others even built elaborate saloons, examples of which still survive in Lake View on North Southport Avenue. The Chicago City Council also contributed to the brewery domination by increasing the saloon license from $50 to $500 between 1883 and 1885 to pay for an expanded police force supposedly made necessary by the barrooms. Relatively few independent proprietors could afford to pay such amounts.

|

Politics was also a natural avocation for saloonkeepers because of the adaptable social nature of their business. In neighborhoods where literacy was low, the bar provided the principal place for the exchange of information about employment, housing, and the many tragedies that beset the city's poor; a savvy politician could turn his access to resources into votes. In slum districts, his place provided a safe for valuables, a telephone for emergencies, a newspaper for the literate, a bowl on the bar for charity collections. In factory districts, saloons became labor exchanges and union halls, as well as providing a place to cash paychecks. On busy streets and downtown, the saloon provided a restroom. And in all areas of the city, the purchase of a drink allowed access to the free lunch sideboard. This feature usually offered only cold foods, but competition could make it elaborate.

|

The first decade of the twentieth century saw increasing accusations of saloon involvement in crime. Complaints about vicious dance halls and alliances with the so-called white slave trade led to passage of a $1,000 license rate in 1906, along with a moratorium on new permits. The latter created a license premium, a value on the transferable right to hold the permit that often reached $2,500 because of the desire of so many to enter the business and the brewers to dominate it. Saloonkeepers also saw their markets geographically limited. Aldermen from outlying neighborhoods had gradually eliminated liquor sales from their voting precincts since the 1890s, but in 1907 the General Assembly passed a local option law that placed the process directly in the hands of the voters. Within two years nearly two-thirds of the city, including virtually all of the land annexed in 1889, was saloonless. By this time, the attack on the segregated prostitution of the Levee district had convinced the burgeoning middle class that the barroom was incompatible with residence districts. Many patrons drank downtown and telephoned for the delivery of liquor to their private sideboards.

|

Prohibition killed the legal saloon in 1920, but over three thousand city speakeasies and dozens of suburban roadhouses, many of them once village taverns, serviced the demand for more secret illegal drinking. When Prohibition ended in 1933, the word “saloon” virtually disappeared from the public vocabulary. Owners instead chose the name “cocktail lounge” or “tavern.”

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.