| Entries |

| Z |

|

Zoning

|

|

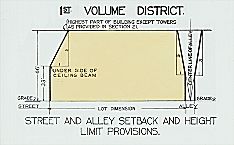

By the early 1910s, city officials were looking for more comprehensive ways to address concerns related to aesthetics and property values. After New York City adopted a citywide zoning ordinance in 1916, attention turned toward the possibility of a similar ordinance for Chicago. The city formed a Zoning Commission that year and in 1919 passed the Glackin Law, named after state senator Edward Glackin, which gave municipalities the authority to regulate land use if they had the approval of neighborhood property owners. If 40 percent approved the zoning plan, the municipality could formulate a zoning ordinance appropriate for the neighborhood. The state repealed the Glackin Law in 1921 and replaced it with a new state zoning-enabling act drafted by the zoning committee of the Chicago Real Estate Board. The city adopted its first zoning ordinance in 1923.

The national zoning movement crossed an important legal milestone in 1926, when the Supreme Court issued its seminal ruling in Village of Euclid (Ohio) v. Ambler Realty Company, which affirmed a municipality's right to practice zoning. As it was first prescribed, zoning was envisioned as a tool primarily to protect the health and safety of residents of single-family homes. As time progressed, policymakers broadened the scope of zoning to protect other types of property and to manage issues related to property values, aesthetics, buildings and sites, and the environment.

The 1923 ordinance proved insufficient to handle the growing complexity of the city and was criticized for allowing nonconforming uses (land uses in violation of the ordinance) to continue. Although the ordinance was revised in 1942, dramatic changes, most notably the rise in automobile travel, necessitated a broad reassessment of the city's zoning policy. The product of this reassessment, the 1957 zoning ordinance, marked a critical moment in city planning history and became nationally known for its emphasis on floor-area ratios, industrial performance standards, and other “scientific” measures to assess the desirability of developments.

The 1957 ordinance, created through the leadership of Harry F. Chaddick, the city's zoning director, played an enormous role in helping manage development in Chicago for more than 40 years. It included, for example, provisions for planned developments (or planned unit developments) that gave developers of larger projects substantially more flexibility than could be provided through conventional zoning. These provisions were gradually refined during the 1960s and proved instrumental to hundreds of development projects.

Over the next several decades, community involvement in zoning decisions gradually increased, and the city adopted several supplemental measures, including the Landmark Preservation Ordinance (1968), Lakefront Protection Ordinance (1973), a Townhouse Standards amendment (1998), and the Strip-Center Ordinance (1999). Although the city attempted to modernize the entire ordinance, these efforts were frustrated by the enormity of the task and the politically sensitive nature of this undertaking. Many felt the 1957 ordinance was too permissive with respect to high-density development.

In response to mounting concerns and a boom in residential construction, the city launched its long-anticipated initiative to overhaul its zoning ordinance on July 26, 2000. Mayor Richard M. Daley appointed a 21-member commission, the Zoning Reform Commission, to rewrite the ordinance. By2004, the city council approved the text portion of the new ordinance, which included a variety of new regulations to enhance neighborhood aesthetics and encourage the development of pedestrian-oriented environments. That same year, the city began the difficult task of revising the zoning maps.

Zoning is also almost universally practiced in suburban communities. In more than 90 percent of municipalities in Cook, DuPage, and Lake counties, zoning is established in accordance with a comprehensive plan, which outlines a municipality's goals and concerns for the quality of life. Although Chicago has many neighborhood and area plans to guide zoning decisions, it does not presently have a comprehensive plan.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.