| Entries |

| L |

|

Land Use

|

|

Recognized as early as 1673 by Joliet and Marquette, the connection between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River offered opportunities not only for exploration and trade, but also for real-estate investment and speculation.

After Indian treaties cleared the way for large-scale settlement and investment, Chicago became a funnel for people, products, and investment dollars to the American West. Well-placed Native American trails and trading routes were transformed into shipping, rail, and highway routes, with settlements providing services. Early traders were joined by farmers, who set the stage for massive agricultural and urban development.

|

The “big shoulders” image of Chicago emerged during the period of extraordinary industrial development of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The iron and steel mills and the oil refineries of southeast Chicago and Gary and along the industrial corridor following the original route of the I&M Canal (later the route of the Sanitary and Ship Canal and the Stevenson Expressway ) became major land users that supported the region's economy and the development of worker housing.

|

After World War II, the square-mile surveyor's grid began to be filled in by the fashionable curvilinear style of subdivision development. Radial and circumferential expressways, together with multilane arterial roadways, added further complexity to the pattern. Land use and real-estate development built on this pattern of the basic grid plus its overlays.

|

The natural attractiveness of certain areas provided another stimulus for real-estate development. The cottages and resorts in the lake district in the northern part of the region gradually converted to full-service communities. Similarly, wealthy city dwellers seeking the country experience led the development of suburban golf courses reachable by commuter rail service, around which grew suburbs such as Flossmoor and Olympia Fields. The stunning Lake Michigan shoreline miles north of downtown Chicago provided captains of industry and civic leaders with an elegant, verdant, and unpolluted residential setting.

|

The disinvestment of urban Chicago and older suburbs seemed to accelerate the “concentric growth phenomenon,” which had been described by urban economists such as Homer Hoyt at the University of Chicago. It was easy to see a concentric pattern of inner core, older inner areas, newly developing areas farther out, and finally, open countryside. In the period between the 1960s and the 1990s this dynamic progression was even more apparent.

|

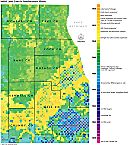

According to NIPC, the explosion of land consumption continued dramatically between 1970 and 1990 with a 40 percent increase in developed land area in the region, while the region's population increased by only 4 percent. More than four hundred square miles of farmland were consumed during this period. Major new development was being experienced in the counties lying just outside the six-county metropolitan area. Other metropolitan areas across the United States were observing the same phenomenon. Therefore, there was an increasing awareness in the 1990s that this growth pattern represented a very real threat to the long-term sustainability of communities and the metropolitan region. Planners in the northeastern Illinois region, as in many other regions, began to call for “smart growth” in order to promote mixed land uses, preservation of usable open space, and viable transportation systems. Federal and state governments were similarly taking up the charge.

Also during the 1990s, Chicago began to experience major new investment in the central part of the city and in other locations as well. Loft conversions, new high-rise apartments and condominiums, new townhouse developments, and infill on individual lots began to bring new vitality back to the city. Local school improvements and reduced crime rates further supported reinvestment in older cities and towns. Some of the older but more desirable suburbs were also experiencing the “tear-down” phenomenon, where historic homes were purchased and demolished in order to build larger structures.

|

At the end of the twentieth century, there were signs of acceptance of new forms of real-estate development and land use. It remains to be seen whether these will become dominant forms and whether the region will find effective means to further a regional vision as it increasingly operates within a global economy.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.