| Entries |

| E |

|

Environmental Politics

|

|

|

From the founding of the city in the mid-1830s to the present, the political formation of urban space divides into five broad periods. During the initial stage of city building, land speculation and development dominated, engendering a “segmented” form of government. The reign of the property owners was expressed in long, thin ward boundaries, which empowered them to make decisions about the pace and cost of infrastructure improvements. An influx of German and Irish immigrants brought a new era of rapid urban expansion and boss rule. A politics of growth characterized the second period, from the inauguration in 1863 of a ward system based on ethnic and class divisions to 1889, the pivotal year of the great annexation and the creation of the Sanitary District of Chicago. A third era of metropolitan integration followed until 1927, when the U.S. Supreme Court seized control of Chicago's sanitation system. The long-running court battle over the city's water management policy was emblematic of the policy dilemmas stemming from the ever-wider environmental impacts of the industrial city on the Great Lakes region. With the coming of the New Deal in 1933, these problems of federalism were resolved to a large extent by a new partnership between the national government and city hall. During the next 40 years, Washington funneled huge sums of money for environmental improvement projects through the local party bosses. They, in turn, spent these funds in ways that promoted personal and partisan goals at the expense of their working-class constituents. A final, fifth period began in the early 1970s, when the national government took more direct responsibility for improving the quality of our air, water, and land. The dawning era of environmental protection encouraged federal bureaucracies and nongovernment organizations (NGOs) to hold city hall to account not only for pollution but also injustice in the distribution of its toxic health effects on poor neighborhoods and minority groups. Although national initiatives have begun to address the imbalance between urban growth and ecological limits, the forces of metropolitan sprawl and spatial segregation remain predominant in defining the quality of the environment in the various districts and suburbs of the Chicago area.

|

Representing a triumph of privatism, the segmented form of government achieved success by avoiding not only partisan conflicts but also policy decisions on an accumulating list of citywide problems. Issues affecting the whole community, such as building bridges, supplying water, and soliciting aid from Washington for harbor improvements—issues that had been previously addressed by a frontier spirit of cooperation—could no longer be resolved within the public arena. After 1848, moreover, swelling numbers of German and Irish immigrants produced a more complex urban society with diverse special-interest groups pursuing conflicting agendas of city building. Large property owners, for example, wanted to protect their investments with tough fire codes, the very regulations that could price most would-be homeowners out of the market.

|

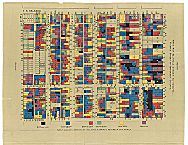

Under the regime of the ward bosses from 1864 to 1889, the politics of growth played a large part in the construction of landscapes of inequality between riverfront slums and lakefront districts. Despite the Great Fire of 1871, Chicago's population doubled each decade, making it the fastest-growing big city in the western world. Just trying to keep up with the incredible pace of this expansion in terms of installing the basic infrastructure of the modern city proved a herculean task. In this era of the horse railway, neighbors could be close geographically but live in totally different worlds in terms of the quality of their air, water, and ground. Whether or not property owners could afford the modern amenities of the built environment further divided the rich and poor into separate spheres. While the middle classes could afford commuter fares, the working classes were forced by poverty to live close enough to their jobs to walk to work.

|

This reordering of urban space into landscapes of inequality took place inside and beyond municipal boundaries. For example, both the exclusive residential community of Hyde Park on the lakefront and the heavily industrial area of the stockyards on the South Branch of the river were located just south of the city line at 39th Street in the “suburbs.” Although they grew up alongside each other with only a few miles in between, they were truly worlds apart. Hyde Parkers made effective use of the public authority to create a buffer zone of protected parks and boulevards that defended their homes against the poor immigrants flocking to the mecca of jobs, Packingtown. In sharp contrast, the city government of Chicago completely failed to stop the environmental degradation that endangered the lives of the families living in “the back of the yards. ” In spite of special powers to regulate the slaughterhouse district, city hall consistently put the profits of the meatpackers ahead of the health and safety of their workers.

|

With the water intake cribs sitting just a few miles out, the aldermen's management of the environment put Chicago's health at risk from a ghastly stew of bacteriological diseases, including cholera, typhoid fever, diarrhea, and diphtheria. Physical and social segregation maintained a barrier between well-to-do and working-class Chicagoans, protecting the affluent from high-mortality airborne diseases such as tuberculosis. But the shield of spatial exclusion was illusory, as contaminated drinking supplies came right into their homes through unseen pipes buried underground. The great flood of 1885 marked a turning point, a crisis that galvanized the middle and upper classes into an irresistible force of public health reform. The Citizens' Association, an elite businessman's group, took the lead in pressuring city hall to support reform legislation that embodied broader metropolitan and regional perspectives on the environment.

|

The year 1889 was pivotal in the history of environmental politics in Chicago for a second reason, the great annexation. Increasing its size fourfold to 168 square miles and its population to over a million people, the enlarged boundaries also created a new set of political dynamics between urban growth and ecological limits, center and periphery, city and suburbs. On the one hand, the additional territory revived competition between the outer and the inner wards for infrastructure improvements. Fulfilling demands for service extensions in new subdivisions at the city's edge often came at the expense of the older, built-up areas where the original utilities dating back to pre–Civil War days badly needed upgrading and replacement. In addition, this competition coincided with the early phases of African American migration from the South. These demographic trends helped tip the balance of infrastructure improvements heavily in favor of the mostly white fringe districts. This lack of distributive justice in turn contributed to the consolidation during the early twentieth century of a new form of spatial segregation, the “ Black Belt. ” Unlike previous neighborhoods defined by class and ethnicity, this kind of racial zone was imposed from the outside, forcing African Americans to live within separate and unequal areas.

|

|

Chicago's long-running battle with the national government over the Great Lakes was emblematic of the new directions of environmental politics in the period leading up to the Great Depression. Under the reign of the party bosses, the sanitary district needed to take huge quantities of water from Lake Michigan in order to keep afloat its pretentious scheme for a deepwater ship canal. Lowering the Great Lakes by as much as six inches, the Sanitary District soon attracted attention from Canadians, who vigorously objected to the resulting economic and ecological damage to the entire region. Assuming the posture of conservationists, Canadian officials exerted unrelenting pressure on Washington to force Chicago to stop its damaging “diversion.” Between 1900 and 1927, however, local politicians defied every attempt by the federal government to get the city to reduce its gluttonous consumption of water by building sewage treatment plants. Frustrated by this recalcitrance, the U.S. Supreme Court finally took over the management of the Sanitary District, gradually bringing it into compliance with the limitations set for the city's withdrawal of water from the Great Lakes. The coming of the New Deal would complete this process of integrating the metropolis into larger webs of regional and national interdependence.

From 1933 to 1970, a new federal partnership between the national capital and the city halls of America helped underwrite a massive public investment in the urban environment. Money flowed through municipal agencies to upgrade highways and sewers, build airports and subways, and replace slum districts with housing projects. In Chicago, this brief era of the urban nation reinforced not only the power of the party bosses but also the existing patterns of social exclusion and physical segregation. The mayor and the aldermen used funds earmarked for slum clearance and public housing to construct a second ghetto of high-rise apartments. They also perverted transportation planning by drawing the routes of expressways to act like a racial Berlin wall. In the post– World War II period, direct federal support to the working classes for inner-city renewal was small compared to the size of indirect subsidies to the middle classes for suburban development in the form of low-cost mortgages, free expressways, and cheap gasoline. By 1970, racial and class discrimination in the political formation of urban space had the ironic effect of ensuring the ascendancy of a suburban nation.

|

At the same time, Congress opened the doors of the federal courts to suits by NGOs against local units of government that perpetuated unfair patterns of resource allocation for public housing and urban services among the city's various neighborhoods. The Chicago Park District and the Chicago Housing Authority were the two agencies most directly implicated in the ensuing judicial assault on the city's politics of environmental racism. In both cases, the court found public officials guilty of discrimination intended to maintain and widen the gap in the quality of life between the white and black areas of the city. In 1969, for example, U.S. District Judge Richard Austin ruled in the landmark Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority that site selection for new construction must begin to reverse the agency's previous patterns of segregation. Stubbornly resisting his decree by refusing to build any additional units for almost a decade, city hall was eventually dragged into compliance by a determined federal jurist. Besieged from the top and the bottom, the local political regime learned that it could no longer afford to make decisions affecting the environment while blatantly disregarding democratic ideals of equality and justice.

After 1970, the political formation of urban space took place within hostile arenas increasingly filled with state and national lawmakers who called for the containment of the city's social and environmental problems within municipal boundaries. Chicago, for instance, lost its grip on the statehouse to an insurgent coalition of legislators from suburban and rural districts. Despite new levels of ecological concern, a suburban majority has continued to support public policies that promote settlement patterns of geographic sprawl and high energy consumption. The state legislature has supported continued suburban growth through substantial appropriations for additional roads and highways outside of the city, while rejecting proposals for more equitable funding to support city schools losing resources to those growing suburbs. Affluent districts have played the self-serving politics of NIMBY to place an unfair burden of health risks from toxic wastes and industrial sites upon impoverished and minority areas. The new perspectives of ecology have illuminated the interconnectedness of the built and the natural environments, the center and the periphery, and the rich and the poor. Yet contemporary society shows few signs of departing from traditions of political culture that express power relationships in spatial terms of exclusion and segregation.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.