| Entries |

| E |

|

Entertaining Chicagoans

|

|

Chicago's nineteenth-century theatrical life exemplifies the first phase. In the 1830s and 1840s Chicago was a male frontier town. The scarcity of women diminished controls of class, family, and culture, leading to a rowdy, egalitarian, male-dominated theatrical life. Initial amusements were transient, mounted for short periods by traveling showmen in temporary quarters. The first theater opened in the vacant Sauganash Tavern banquet hall in 1837 as a makeshift affair, with rude sets and rude chairs, “all on the level floor, where all men sat in a spirit of equality.” Similarly, the Rialto opened as the city's first permanent theater in the spring of 1838 in an old auction house on Dearborn Street. Like its predecessor it was “a den of a place, looking more like a dismantled grist-mill than a temple.” No theater lasted long until the 1840s and 1850s.

Early theaters featured a wide variety of entertainments. Performances were long, from 7:30 p.m. until midnight, and theatrical bills consisted of a drama, a farce, and an afterpiece. This left room for a mix of attractions for every taste—romantic melodramas and comedies—punctuated by song and dance in and out of blackface. Shakespeare was the most frequently performed playwright in the city, appearing in the same milieu as circus acts, dancers, singers, minstrels, and comics. Often, the same performer went from Shakespeare or melodrama to popular songs on the same bill. At a benefit for the Rialto Theater, an actor performed Macbeth but between plays sang “Tam O'Shanter.” At another benefit, an actor followed a melodrama with Andrew Jackson's campaign song, “The Hunters of Kentucky.”

|

The first phase of entertainment gave way after midcentury to a separation of high and low cultural appetites. During the 1850s and 1860s, theater managers struggled to control audience behavior and place their theaters on a solid paying basis. They did this by refining theatrical life to make it suitable for middle-class women. The Rice Theater (Randolph near Dearborn), for example, opened in 1847, burned down in 1850, and lacked stable profits. In 1853 John B. Rice redecorated to lend the theater an air of cultivation. To control rowdy male patrons, he transformed the pit, the area most associated with unruly mobs, into a parquette with the addition of comfortable seats and added elegantly furnished boxes. Financial difficulties forced Rice to give way to J. H. McVicker, whose new theater in 1857 cost $85,000 and was a major step in the attempt to legitimize the acting profession and uplift the drama. Located on Madison Avenue between Dearborn and State, McVicker's was bigger and more grandiose than its predecessors. Program notes for 1858 suggest attempts at gentility, with the parquettes for gentlemen and the admonition “no improper characters allowed in the theater”—an allusion to prostitutes and rowdies. In response, the press hailed McVicker's in 1859 for bringing “a better class of entertainment” in keeping with “the artistic tastes of the public.”

|

By refining some of the city's drama with an emphasis on bourgeois decorum, theater managers made it possible by the 1870s and 1880s for women to become the mainstay of the matinee audience. Melodrama proved the backbone of popular theater, for it dramatized the official values of late-nineteenth-century Chicago by emphasizing that self-control and female refinement formed the basis of American civilization and progress. Attracting both men and women, melodrama featured male heroes who rescued virginal heroines. The hero's will set him apart from villains either poor and vicious or rich and decadent. By drawing on his internal morality to depose external authority symbolized by the villain, the hero demonstrated an allegiance to the refined heroine, the private family, and sexual restraint. To appeal to large female audiences, melodrama examined the demands of home and family and punished those women who strayed from its bounds.

|

By the 1870s, as part of growing specialization, minstrelsy was housed in its own separate theaters or appeared for a run at North's Theater. It also increasingly harkened nostalgically to a sentimental rural past free of industrial conflicts. Greater emphasis was placed on sentimental ballads and virginal belles, and with its sensual implications diminished, it was considered more suitable for white women.

Encamped in open spaces downtown, circuses dramatized the battle between civilization and nature. Once circuses regulated prostitutes and the carny atmosphere, they attracted family audiences. Featuring the struggle between beasts and animal trainers and equestrian daredevils, the circus enacted the progress of morally and physically courageous men and women over nature. The use of three rings in the 1880s and the elevation of circus owners to big businessmen symbolized the taming of nature, the growing power of hierarchical economic institutions, and the taming of audiences. A variant, Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, proved a major Chicago attraction from the 1880s through World War I, as it enacted the triumph of white American civilization, rooted in white womanhood, the private family farm, and the railroad over primeval nature, wild animals, and savage races.

|

Staged in concert saloons, “variety” specialized in the rough male elements linked to the alcoholic intimacy and uproarious crowd behavior that had come to be excluded from more orderly theaters and considered too disreputable for respectable women. Variety featured song, dance, comedy, and waiter girls who served liquor and performed for the enjoyment of males. Because of the mixture of sex, alcohol, and audience participation, connoting unruly male passions, concert saloons had a poor reputation. Burlesque also occupied a low place of amusement. When Lydia Thompson's British Blondes appeared at Crosby's Opera House in 1869 and 1870, they created a sensation; even middle-class women wanted to see their half-clothed verbal send-ups of current affairs. After editor Wilbur F. Storey attacked the troupe, however, a scandal erupted. As a symbol of the dangerous sexual impulses that the theater struggled to erase, the erotic burlesque female thereafter was cast from reputable middle-class amusements and appeared on stages specifically designed for male patrons only.

Public dance halls also challenged values of work, order, and restraint. Back in 1833 everyone had danced at the Sauganash Tavern, but after the Civil War, because many halls were in red-light districts and served alcohol, public dancing in Chicago assumed a notorious reputation. With saloons, brothels, and gambling dens, the Levee lured men of all classes who enjoyed the rough equality and anarchic behavior of a legal vice district. As a result, the middle and upper classes organized their intimate activities, such as dancing, in the privacy of their homes or the carefully restricted world of society dancing master's halls and balls, while members of the working class enjoyed their dances as part of the benefits and celebrations of ethnic communities aimed at the entire family, thus safeguarding young women.

This divided world of amusements gave way to a third phase of entertainment around the turn of the century, as new entertainments, rooted in a new heterosocial ethic, stood poised to become regular parts of urban life. The demand for new forms of amusement lay in a psychic revolt against the feminization and rationalization of urban life during the late nineteenth century. The growth of a model of success based on money, consumption, and pleasure enabled rich and poor to shape entertainment. Rising wage rates enabled children of new immigrants to seek relief from mechanized jobs and entree to a wider American world through participation in cheap amusements. Similarly, white-collar workers turned to leisure to express their individualism outside corporate offices. At all levels, young women now worked outside the home and sought after-work leisure traditionally enjoyed by men. With time and some money to explore personal identity apart from family, they helped transform courting and youth culture and deeply influenced modern entertainment.

|

Vaudeville, with its aura of consumption, was also designed to welcome a mixed-sex audience and depended on public transportation to bring heterogeneous audiences. New vaudeville circuits refined low-class variety in order to attract women and children. Luxurious decor and decorous treatment gave everyone a sense of wealth and comfort. Ushers treated all white women as ladies, while the variety of acts reflected the diversity of city life: circus and minstrel acts, ethnic comedians, and dancers satisfied all tastes. Vaudeville also interpreted the material world of technology, money, and enjoyment for urban audiences, redefining success to mean enjoyment of wealth rather than its pursuit. Like all the new urban amusements, vaudeville proclaimed its respectability in order to attract women and families, but it also promised a new vitality and personal freedom distinct from Victorian codes of propriety. Singers like Eva Tanguay and Sophie Tucker, for example, offered thrilling glimpses of female sexuality. Chicago's vaudeville theaters were the second stop on the national circuits, and by the 1910s the Majestic and the Palace featured only headliners.

As the second major market in the country, Chicago played an important role in American movie history. Chicago's role initially involved production. William Selig built Polyscope, the world's first movie studio, in Chicago in 1897. By 1907 his studio, at Irving Park Road and Western Avenue, was the country's largest. Founded the same year, Essanay grew out of the partnership of George K. Spoor and cowboy star “Broncho Billy” Anderson. The Motion Picture Patents Company, to which both studios belonged, prospered with stars like Gloria Swanson, Francis X. Bushman, and Charlie Chaplin. California's better weather, however, combined with a court ruling that declared the company's exclusive right to motion pictures unconstitutional, shifted film production away from Chicago by World War I.

|

Dance halls followed a similar path. Linked to vice, they only slowly gained public acceptance. By 1900 saloons opened annexes for dancing to meet the demands of young working-class women eager for inexpensive places to meet members of the opposite sex apart from parents. Worried about the dangers to young women, reformers during the 1910s banned alcohol, censored close-hold ragtime dances, and opened city halls. These reforms alerted entrepreneurs to the dance hall's commercial potential. Working closely with reformers, the Karzas Brothers opened the Trianon Ballroom in 1922 at 62nd and Cottage Grove Avenue with a no jazz policy and floor spotters to police the crowd. In 1926 they opened Uptown's Aragon Ballroom. Both spots attracted a lower-middle-class and working-class clientele. Free from disreputable associations, ballrooms used luxurious palatial designs to uplift sex into romance.

As with other amusements, the pursuit of decorum and the fear of sex led to rigid racial segregation. But in the twentieth century, even the well-to-do sought ways to break down the cultural barriers that had set them off from the lower classes. Cabarets allowed affluent men and women to interact in new ways in settings of public anonymity. Initially, saloons cleared away tables, put in dance floors, and hired performers to form cabarets. Cabarets stressed informal, intimate entertainment on the floor and among the tables, breaking down barriers between performer and audience, and spurring guests to express themselves. Cabarets relied on the dance craze of the 1910s to become public meeting grounds for men and women who sought intimacy in new ragtime dances such as the Turkey Trot and Bunny Hug that arose out of black dance and lower-class pastimes. Cabarets were also the first public places to permit women to drink. To offset the danger in women's new behavior, cafes stressed their reputable character. The Edelweiss Gardens presented “Dining, Dancing and Entertainment” in “the most charming environment” and hired high-class ballroom acts, as did the Sherman Hotel's College Inn. The Movie Inn (17 N. Wabash) opened in 1915 to meet the demand for public dancing. Its booths named for movie stars, the Inn attracted players from Essanay studio but ran into trouble when gigolos appeared in the afternoon squiring married women. Fearful of mixing between women performers and audiences and the expression of body impulses in the ragtime dances, moralists protested afternoon dancing but lost in court when reputable venues objected.

By the 1920s Chicago nightclubs symbolized big-city lawlessness and the moral rebellion of Prohibition. As speakeasies, they came under the control of criminals like Al Capone and Bugs Moran. The attraction of risk, public intimacy, and the chance to see lively entertainment and rub elbows with celebrities made clubs popular. Nightlife was so popular that roadhouses, often run by the mob, opened in incorporated areas from Stickney to Niles so urbanites and suburbanites might enjoy a night out. Uptown's ballrooms and clubs abounded. The Green Mill (Broadway and Lawrence) presented top acts like Sophie Tucker and Joe E. Lewis. Towertown, north of the river, had dives for the underworld and transients who filled the furnished rooms west of Clark, clubs for nearby Gold Coasters, and arty bohemian gay spots. In the Loop, Friars Inn, Ciro's, the Hotel Morrison's Terrace Room, the Blackhawk, and many more enlivened nightlife by allowing women to drink, dance, and socialize on the same level as men.

Black Chicagoans participated in this entertainment upsurge, but in a separate amusement zone on the Stroll along 35th and State Streets. While Chicago's amusements elsewhere represented a new, wider public sphere, white skin remained a prerequisite for admission. African Americans found themselves excluded entirely in the most intimate of entertainments or, in the case of theaters, segregated to balconies. They sued theater owners, but their major action was to build their own theaters, saloons, and cabarets, starting with the Pekin, the nation's first black-owned theater, opened in 1905 by Robert T. Motts. By the early 1920s, numerous places existed for black workers to dance or see a show on the Stroll. Among the cabarets and dance halls were the Dreamland Cafe, Lincoln Gardens, the Entertainer's Cafe, the Sunset, Plantation, and the Apex. For migrants from the South, clubs helped ease the transition between rural mores and city culture.

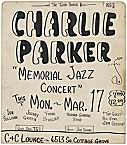

With the South Side's cafes and dance halls booming, Chicago was America's jazz capital during the twenties. Musicians from New Orleans and other parts of the country followed their audiences to the city as part of the “ Great Migration. ” King Oliver's Dixie Syncopators (with Louis Armstrong), Carroll Dickerson's Orchestra, Earl Hines, Zutty Singleton, Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Bessie Smith, clarinetist Jimmie Noone, and many more played all over the South Side. White slummers bent on losing their inhibitions in “black and tans” soon followed, as did the many white jazzmen who sought to learn the new expressive music from the artists who had created it.

From 1900 to the 1920s, Chicago enjoyed an explosion of popular culture. Movies, amusement parks, vaudeville, cabarets, dance halls, and music deeply influenced the Jazz Age. The new amusements redefined success to include pleasure and consumption, and as mixed-sex institutions they also created new ways for men and women to court, establishing greater equality for women in leisure activities. Technology, long the bane of the working class, was glorified as an agency for human pleasure. It was considered dangerous for blacks and whites to mix too intimately, so African Americans were kept outside the influence of assimilation that immigrants enjoyed. Segregated from white amusements, black Chicagoans pioneered their own. Their creative revenge was jazz, and Chicago became a capital of the new music. The Great Depression of the 1930s brought this explosion to a momentary close. Entertainments would reopen in different forms after 1934, when repeal of Prohibition and the New Deal restored people's spirits, but the outline of modern amusements had already been established in Chicago in the preceding decades and over the preceding hundred years.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.