| Entries |

| P |

|

Police

|

Policing in the Nineteenth Century

|

This decentralized, reactive police system was in keeping with traditional fears of despotic government and was well adapted to the concerns and sensibilities of merchants, professionals, and influential citizens. But disorder was more dangerous than a growing government presence. Commercial and industrial progress seemed increasingly hard to reconcile with rowdiness, drunkenness, or violence, while riots grew harder to control in a more sharply class-divided society.

The spark for establishing a centralized, bureaucratic, uniformed police came when the nativist American, or “Know-Nothing,” Party won elections and raised saloon license fees, precipitating the “ Lager Beer Riot ” of April 21, 1855, in which German and Irish crowds fought the existing police and militia.

The city council quickly established the Chicago Police Department, organized into three precincts and commanded by Chief Cyrus P. Bradley. All of the first 80 recruits were native-born, and liquor regulations were vigorously enforced.

Modeled on forces in London and New York, the new “preventive” police were salaried, full-time officials who patrolled day and night. Uniformed in 1858, they were highly visible representatives of public authority.

|

Police were ordered to regulate saloons and suppress vice, but bribery and political interference discouraged enforcement, though police did restrict vice to specific areas and tried to impose outward order. Lurid corruption scandals ensued, though most patrolmen benefited little from graft.

|

Controlling crime and violence was but one among many police jobs. Police controlled traffic at bridges, helped pedestrians cross downtown streets, and gave directions to strangers. They returned lost children, reported broken street lamps, and stopped runaway horses. Thousands of homeless people slept in station houses every year. Murder rates were low, and serious crime relatively rare. A detective unit was established in 1860, and a rogues' gallery in 1884. But dragnets, lengthy detentions of suspects without legal safeguards, and forced confessions were also employed.

Initially, the mayor and city council appointed officers. In 1861, control was placed in three commissioners, state appointed, later elected; the mayor and council regained control in 1875. The superintendent (as he was known after 1861) was often a weak leader. Despite centralized policies and practices, the captains who ran the precincts or districts were relatively independent of headquarters, owing their jobs to neighborhood politicians. Decentralization meant that police could respond to local concerns, but graft often determined which concerns got most attention.

Political connections were important to joining the force; formal requirements were few until 1895. After 1856, the department hired many foreign-born recruits, especially unskilled but English-speaking Irish immigrants. The first African American officer was appointed in 1872, but black police were assigned to duty in plain clothes only, mainly in largely black neighborhoods. Women entered the force in 1885 as matrons, caring for female prisoners. “Policewomen” were formally appointed beginning in 1913, to work with women and children. In 1895, Chicago adopted civil service procedures, and written tests became the basis for hiring and promotion. Standards for recruits rose, though policing remained political.

|

Discipline, critics argued, was weak, and Captain Alexander Piper's famous 1904 investigation found police lounging on street corners, loafing in saloons, or simply absent from duty. Such complaints ignored patrolmen's grueling schedules and their thousands of arrests and services provided. Weak discipline was probably most evident in the inability of police administration to control excessive violence or graft.

Chicago's police were first to adopt a “signal service” in 1880, combining telegraph and telephone, to allow patrolmen on their beats to summon an ambulance or patrol wagon. Patrolmen were required to report hourly to ensure they were awake and on the job. A few “respectable” citizens were given keys to the signal system, which was also used as a field communications system for controlling crowds and riots. The practice of preventive patrol never matched its promise. Nonetheless, arrests declined, and some observers agreed that the streets—the patrolman's domain—were more orderly at the century's end.

Other law enforcement agencies had jurisdiction within metropolitan Chicago, including the county sheriff and the U.S. Secret Service, but far more important were suburban forces. In many outlying communities, law enforcement was still the province of constables, who provided limited, reactive policing. Some larger suburbs, such as the village of Hyde Park, the town of Cicero, and the city of Evanston, organized their own police forces. Many of these forces were poorly equipped or too small, one of the many reasons inducing some suburbs to seek annexation to Chicago in 1889. With the city's expansion, some 266 suburban officers were brought into the Chicago Police Department, which added other officers and built seven new station houses to cover the new territory.

1900–1960

The Chicago Police Department, by far the largest police agency in the region, grew from 3,314 employees in 1900 to 10,535 in 1960. There was little change in the pattern of arrests. In 1907, the average officer on a beat made 30 arrests per year, roughly half for disorderly conduct, drunkenness, or vagrancy. But bootlegging, scandal, and crime control received far more public attention.

A growing anti-vice movement pressured police into cracking down on the city's vice districts before World War I, but under Mayor William Hale Thompson (1915–1923, 1927–1931), Chicago was an “open town” for bootlegging and vice. Police were unable to overcome corruption and inefficiency to make arrests in gangland murder cases. A new administration from 1923 to 1927 attempted to suppress bootlegging, but the number of murders only rose.

Thompson's policies, along with fears of postwar “crime waves” and “auto bandits,” led businesspeople and reformers to organize the Chicago Crime Commission and other anticrime groups, which were modestly effective in pressing for reforms. In 1929, the police department, with Northwestern University, established a crime laboratory, its most notable improvement in scientific policing since the adoption of fingerprinting in 1905. Formal police education, dating to establishment of the Police Academy in 1910, expanded from four weeks to three months of training in 1929.

|

Rank-and-file police groups organized to influence legislation and considered unionization during World War I. In 1944, the superintendent quashed a budding union. But police salaries remained relatively attractive, and schedules improved as reserve duty was reduced, then eliminated. By 1931 police worked a 48 hour week and enjoyed 15 days of vacation yearly. By 1960, their work week was 40 hours, though they still rotated shifts every month.

|

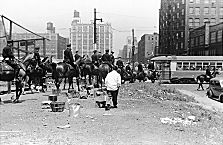

African Americans were better represented on the force than in other big cities and were slowly promoted, reaching the rank of captain—the first in the United States—in 1940. But black officers could not arrest white citizens, and black sergeants were never assigned to supervise white officers. Black citizens complained of arrests made for flimsy reasons, confinement of vice to black neighborhoods, and enforcement of de facto segregation on the beaches. The Race Riot of 1919 began when a white officer refused to arrest whites suspected in the fatal stoning of a black swimmer, and, after the riot broke out, police continued to fail to enforce the law evenhandedly.

|

National police agencies became more important in the 1920s. Prohibition brought Chicago a small number of federal agents, many corrupt, though federal agents managed to send gangster Al Capone to prison in 1932. New laws extended the federal government's criminal jurisdiction, and the FBI stepped into a highly visible enforcement role, tracking down John Dillinger in 1934 and providing local police with fingerprints, crime statistics, training, and the services of a crime lab modeled on Chicago's. From World War I on, federal agents spied on or suppressed antiwar dissidents, “enemy aliens,” Communists, and other radicals.

1960–Present

Scandal over police involvement in a burglary ring prompted Mayor Richard J. Daley to appoint Orlando W. Wilson as superintendent of police in 1960. The nation's foremost expert on police administration, Wilson implemented an ambitious program of reorganization, emphasizing efficiency rather than ward politics. Wilson moved the superintendent's office from City Hall to Police Headquarters and closed police districts and redrew their boundaries without regard to politics. Hiring standards were raised, graft curbed, and discipline tightened, with a new Police Board overseeing it. Wilson updated the communications system, adopted computers and improved record-keeping, bought new squad cars, and eliminated most foot patrols. Police boasted of quicker response times to citizen calls. Police morale, and the public image of the police, rose.

Wilson also improved police relations with the black community. He recruited more African American officers, promoted black sergeants, and insisted on police restraint in racially charged conflicts. Wilson's retirement in 1967 came both as racial tensions intensified and disputes over policing grew more heated, and the example of his forceful leadership was not followed.

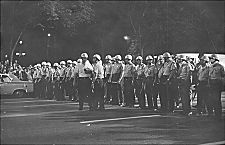

|

On December 4, 1969, Black Panther Party leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were shot and killed by officers working for the state's attorney. Though the police claimed they had been attacked by heavily armed Panthers, subsequent investigation showed that most bullets fired came from police weapons. Relatives of the two dead men eventually won a multimillion-dollar judgment against the city. For many African Americans, the incident symbolized prejudice and lack of restraint among the largely white police. The incident led to growing black voter disaffection with the Democratic machine.

|

Postwar courts increasingly restricted police discretion, restraining police search and interrogation practice. In 1985, a federal court ordered an end to police department “ red squad ” surveillance of radicals, minority organizations, and dissidents.

Federal affirmative-action rulings increased the presence of women in policing. As late as 1958, the force included only 85 women, many in stereotyped “policewoman” positions. Starting in 1974, women were appointed as full-fledged officers and assigned to regular patrol. By 1995, 18 percent of the department's sworn officers were female. Some 25 percent were black and 9 percent Hispanic, and a majority had at least some college education. Police were also unionized, something Mayor Daley had staved off. In 1981 the Fraternal Order of Police signed a contract with the city.

Growing use of computers in the late twentieth century meant that ordinary police officers were more tightly connected to citywide and indeed national institutions and networks of information on drivers' licenses, outstanding warrants, and the like. Telephone communication made it increasingly likely that police would be summoned into citizens' homes.

But twentieth-century reforms generated unexpected problems. New technology and patrol practices, centralization, and elimination of political influences seemed to cut police off from city communities. Neighborhood patterns of crime and disorder were ignored, opening the door, many believed, to increasing crime and delinquency. As early as 1972, radio-dispatched patrol cars were unable to ensure rapid response to the growing volume of citizen calls for service, and radio motor patrol proved surprisingly problematic in curbing crime. Police began searching for methods to circumvent the burden of calls and to reach out to the city's neighborhoods. In 1992, the police department announced the Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy, aimed at bringing officers closer to citizens, returning decision-making to the neighborhood level, and encouraging initiative by beat officers. Community policing reversed decades of reformist thinking.

Postwar urban sprawl generated hundreds of suburban police departments, most small, but some, by the 1990s, with as many as 200 employees. Sheriff's police departments grew throughout the region, to patrol unincorporated areas and aid local police.

Federal law enforcement agencies, especially the FBI, have expanded their local role since the 1960s, notably against criminal organizations, drug traffickers, and corrupt public officials, including, among others, local police. The federal government has funded some local police activities, and federal, state, and local police have routinely cooperated in drug investigations and rounding up fugitives.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.