| Entries |

| D |

|

Dance Halls

|

|

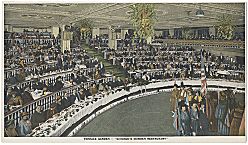

Because of close links with vice, dance halls only slowly gained public acceptance. By 1900 saloonkeepers opened annexes for dancing to meet the needs of the growing working classes who sought release from factory routine. Through World War I, reformers tried to stop alcohol consumption, regulate the types of dances (especially the new ragtime “close-holds”), and open municipal halls as alternatives for the young women who named dancing their favorite recreation. Attempts at regulation alerted entrepreneurs to the dance hall's commercial potential. In 1922 the Karzas brothers opened the Trianon at 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue with a major society gala, a “no jazz ” policy, and floor spotters to police the crowd. Like its North Side sister the Aragon (1926–), the Trianon attracted white lower-middle- and working-class youth. Free of ties to lower-class vice, the Karzas used design and decoration to evoke refinement and luxury for ordinary people while uplifting “dangerous” sexuality to the level of romance.

|

Dance halls flourished through World War II, but postwar domesticity, white flight, suburbanization, and television aided their decline. Whites desired to escape the growing black communities and their demands to be allowed into formerly all-white halls. Many halls closed rather than integrate.

In an age of privacy, the era of the grand urban dance halls has ended.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.