| Entries |

| E |

|

Economic Geography

|

|

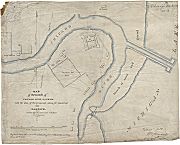

Chicago developed because its site was convenient for commerce. For hundreds of years, American Indians gathered each summer to trade where the Chicago River enters Lake Michigan. In 1673 the French explorer Louis Jolliet recognized Chicago's potential for wider trade: it sits on a low divide between the drainage areas of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River, and only one large portage breaks an all-water route between Lake Michigan and the Gulf of Mexico via the Chicago, Des Plaines, Illinois, and Mississippi Rivers. During the rainy season, the “Chicago portage ” between the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers could be traversed by canoe. Jolliet suggested cutting a canal across this portage to link the Gulf and French Canada, but French officials ignored him.

|

National business and political leaders created the conditions for the rise of Chicago in order to develop the country's western territories. When New York's Erie Canal connected the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean in 1825, they searched for a port at the western end of the lakes to serve the potential trade with new settlers. Eastern businessmen and Illinois politicians revived Jolliet's vision to connect the lakes to the Mississippi through Chicago, and, in 1829, state legislators began planning the Illinois & Michigan Canal.

For easterners to settle northern Illinois, however, the Indians had to be dispossessed. In 1833 the federal government pressured the united Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa nations to cede all their lands east of the Mississippi River, opening the path for easterners to seek their fortunes in northern Illinois.

|

|

|

The national economic depression of 1837 halted work on the canal and the railroad. Trade atrophied, and Chicago land values plummeted. In 1840, Chicago was a small city of more than four thousand people, with the outline of the transportation network that would make it the center of wholesale trade in the west. Once the national economy revived in the mid-1840s, Chicago's potential came to fruition.

|

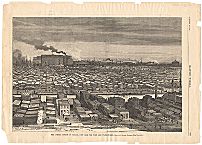

Private companies built railroads radiating out from Chicago in all directions to tap the farms of the Midwest. By 1856, 10 trunk railroads ended in Chicago, making the city a breakpoint for railroad traffic as well as waterborne trade. Tracks paralleled the river and canal to facilitate transfers of goods between railroad cars, canal barges, and lake ships. The wholesale traders set up along the river on South Water Street to direct this commerce. By 1854, Chicago claimed title as the greatest primary grain port in the world, and the grain elevators lining the river dominated the skyline. The grain trade grew rapidly as a national speculative futures market developed. The telegraph made such a market technologically feasible, but the Chicago Board of Trade made it a reality. It created standards and measures such as grades of wheat along with an elevator inspection system, giving eastern capitalists enough confidence to invest in grain sight unseen. The lumber trade also boomed, as lumber from the Midwestern woods was shipped by boat across the lake to be milled in the city. A huge lumber district, with sawmills and extensive storage yards, developed on the Chicago River's South Branch. After milling, the lumber was shipped by rail mostly to the west to build farmhouses, barns, and fences.

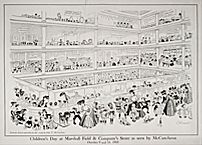

Chicago merchants combined wholesale and retail operations; they sent dry goods to small stores throughout the Midwest and kept stores in the city center for travelers and residents alike. The large retailers congregated on Lake Street, and Chicago's department stores developed as these establishments enlarged and diversified. The downtown rose around the wholesalers and retailers with hotels, restaurants, saloons, and less reputable businesses to service traveling men and conventioneers.

Although the wholesale trade was the most important element in Chicago's economy until the 1870s, industries for processing agricultural and raw materials also developed. Pork—salted, pickled, and otherwise preserved—was the primary product manufactured for easterners. At the same time, Chicago businessmen saw the potential of producing goods for farmers in Chicago rather than acting as middlemen for eastern manufacturers. In 1847 Cyrus H. McCormick opened his reaper works and initiated one of the city's most important industries— agricultural machinery.

|

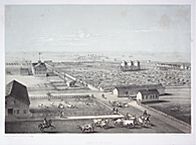

Contracts for supplies for the Union forces also stimulated Chicago enterprise, especially among the meatpackers. The packing plants, scattered around the city, had always been a nuisance because they created pollution. Now huge numbers of animals driven through the streets caused total congestion. Chicagoans wanted the plants moved, and the packers needed more space for pens and better access to railroads to minimize production delays. Chicago's first planned manufacturing district—the Union Stock Yard —opened in 1865 to solve these problems. The packers and the railroads chose a site just outside the city limits at 39th Street and Halsted Street. With access to the canal and major railroads, it was the prototype of future industrial developments that would move to the edge of the city in search of space and better transportation.

By the end of the Civil War, Chicago was poised to build on its dominance of Midwestern trade and its manufacturing base. Growth came quickly, as the completion of the transcontinental railroad enabled the vast expansion of Chicago's potential market. Federal subsidies underwrote this rapid development, in the form of land grants to railroads laying new track. Once again the joint efforts of politicians and businessmen secured Chicago's future. As the eastern terminus of important western railroads and the western terminus of eastern railroads, Chicago remained the central transfer point for people and freight. In the next decades, railroad building devoured more of Chicago's physical space, and rights-of-way guided the siting of industry and residences.

The Great Fire of 1871 decimated the center of the city, but it did not slow development. It spared most of the outlying areas, including the manufacturing district, the lumber district, the Union Stock Yard, the grain elevators, and the railroad freight terminals. This infrastructure supported the rapid rebuilding of the central business district and residential neighborhoods because it gave eastern investors who financed reconstruction confidence that the city would recover and investors would profit.

|

As production at the stockyards increased, the residential neighborhoods around the factories grew polluted and congested. The slums of Packingtown were peopled by poor workers, primarily immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe who struggled to support their families and sustain their cultural traditions. Large working-class neighborhoods characterized by industrial pollution, congestion, poverty, and cultural diversity developed wherever industry located.

|

New industries such as iron and steel production also pushed Chicago ahead of other cities. The North Chicago Rolling Mill produced the city's first steel rails in 1865 but soon relocated to South Chicago. This move signaled not only its need for more space but also a new factor in the city's economic geography. The transcontinental railroads skirted the bottom of Lake Michigan, and production costs were minimized for manufacturers who obtained access to both lake boats and railroads by locating there. The new steel plant, which later became the United States Steel South Works, anchored the north end of the vast iron-and-steel-producing district that developed along the lake from South Chicago to Gary, Indiana. Like the stockyards, it attracted workers, especially immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, and created new neighborhoods on the fringes of the city.

|

|

Perhaps the most important resource of the central city was the concentration of modes of communication. Chicago's printing and publishing industry, second only to New York's, developed with companies such as R. R. Donnelley & Sons, which located near the downtown because of the demand for business information and the proliferation of commercial journals. Chicago businessmen who pioneered and came to dominate a new form of trade— mail-order houses—also utilized this concentration. Montgomery Ward was first in the field, but Sears, Roebuck & Co. became even larger. This revolution in retailing used printed catalogs to reach out to individual customers in rural areas and created white-collar “factories” in the center city—office buildings full of clerical workers who processed orders that arrived by mail and filled them from huge warehouses situated on the river and the railroads.

|

The growing demand for office space in the Loop led upward because of the constricted area. The skyscrapers of Chicago became the symbol of business success and set the architectural fashion for central business districts throughout the country. The Loop's clerical and managerial workers used public transportation to commute to a variety of residential neighborhoods. Districts of boardinghouses and apartments for those without children and middle-class housing for families sprang up in a ring around the inner areas. Construction was the city's largest employer and real-estate speculation was still a major avenue to wealth. Some contractors, such as S. E. Gross, built large developments of single-family houses, comparable in scale to more recent subdivisions.

To maintain their economic prominence, Chicagoans sponsored more transportation improvements, like the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, built in the 1890s to replace the obsolete Illinois & Michigan Canal. Like comparable projects, it boosted industrial development outside the city limits. The Chicago Outer Belt Line Railroad, completed in 1887, facilitated freight traffic and spurred manufacturing in Chicago Heights, Aurora, Joliet, and Elgin. Although outlying areas had always attracted industry, the implications for Chicago changed in the twentieth century. When the city limits reached already established communities such as Oak Park and Evanston, Chicagoans found the path to expansion blocked. After 1900, outlying communities resisted annexation to Chicago, and the metropolitan area developed as an integral economic unit without political control or social unity. The limits on Chicago's development were set.

After 1920, the suburbs grew faster than the city. New transportation, the car and the truck, encouraged the suburbanization of people and industries and reversed the century-old pattern of increasing concentration. Railroads spurred suburban development, but always along their rights-of-way. Cars and trucks allowed industries and people to disperse throughout the area. This provided the large tracts necessary for the single-floor factories that utilized continuous-flow automated technologies.

As deconcentration increased, however, the metropolitan economy also experienced new competition. Detroit monopolized the most important new industry of the early twentieth century— automobiles. Even more significant were long-term shifts in regional development; the Midwest stagnated as the West and the South boomed. After 1920, cities in the Sunbelt enjoyed the advantages in location and transportation that previously had stimulated Midwestern economic growth. Chicago businesses reeled during the Great Depression of the 1930s and then boomed because of World War II defense contracts, but the regional shift determined the long-term trend in economic growth and hence in population, and in 1990 Los Angeles surpassed Chicago as the second city in population and wholesaling.

Chicago's economy did not fall behind for lack of leadership or innovation. Businessmen and politicians fostered transportation improvements such as the Mississippi-Illinois Waterway to accommodate modern barge traffic. Chicago port facilities modernized, although, like many economic functions, they did so by moving out of the center of the city. After the Cal-Sag Channel between Calumet Harbor and the Illinois River opened in 1922, Calumet Harbor replaced the Chicago River as the city's port. Chicagoans also embraced new technologies and developed Midway Airport in the 1920s, making Chicago the breakpoint for cross-country air traffic as it was for water and rail. The country's largest airline, United, headquartered in Chicago. To maintain the country's busiest airport after World War II, Chicagoans developed the larger, more modern O'Hare.

|

Between 1920 and 1970, the Chicago area retained most of its traditional industries. In 1954, it even surpassed Pittsburgh, the old leader, in iron and steel manufacturing, producing one-quarter of the nation's output. Production remained high in machinery, primary metals, printing and publishing, chemicals, food processing, and fabricated metals. The consumer electronics industry expanded greatly, as firms such as Motorola, Zenith, and Admiral captured a significant share of the market for radios and televisions. The first big loss, however, was meatpacking. The industry had been decentralizing since the turn of the century, as Chicago companies shifted to multiple plant locations in western cities, closer to the feed lots. The Chicago stockyards closed in the 1960s.

Although the area's industrial economy remained strong, the city's did not. Companies closed aging factories in the city and shifted work to new suburban plants. The McCormick Reaper Works was demolished in 1961; production was taken over by a new plant south of Hinsdale. Many new industries, such as Sara Lee's frozen foods, began in the suburbs. As jobs became more plentiful outside the city, people migrating to the Chicago area often settled in the suburbs, bypassing the city entirely. This was only true, however, if the migrants were white; because of discrimination, African Americans were restricted to the city. Out migration accelerated after 1950, when the city's population peaked at 3.6 million people. White people followed the jobs, as Chicago's share of the area's manufacturing dropped from 71 percent to 54 percent between 1947 and 1961.

|

The Loop's retail functions also ebbed. Marshall Field's and other Loop department stores opened their first branches in the suburbs in the 1920s. City officials replaced the cluttered and decaying South Water Street with Wacker Drive in the 1920s, but new building in the Loop virtually ceased for decades while North Michigan Avenue became the Magnificent Mile. Suburban competition became intense in the 1950s with the opening of shopping malls. Loop retail trade declined, but the Loop continued to attract conventioneers after the construction of McCormick Place Convention Center. Loop Hotels, theaters, and museums drew tourists to the lakefront of the central city.

|

The service sector is the source of most new growth for the metropolitan economy. The old central city is almost totally dependent on business services and tourism for its vitality. Where the river empties into the lake, a ferris wheel replaces the grain elevator as a symbol of what makes the city great. The diversity of the area's economy remains a strength, but its future, like its past, will depend on national and international economic trends. Chicago was geographically well situated to become the capital of the Midwest. It retains this position, but the old dream of dominating the continent has died.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.