| Entries |

| B |

|

Breweries

|

|

In 1833, German immigrants established the first brewery in Chicago. Soon renamed the Lill and Diversey Brewery, it made English -style ales and porters. In 1847, however, John A. Huck opened the first German-style or lager beer plant and an adjacent beer garden on the Near North Side. The city's swelling numbers of Irish as well as Germans preferred this lighter, more carbonated cold drink, relegating traditional brews to a small specialty market. The brewery's insatiable demand for ice in making and storing its highly perishable food product was largely responsible for creating the ice business in Chicago. In a similar way, its needs for strong animals to pull wagons laden with heavy barrels of beer to saloons and restaurants across the city on a weekly basis helped establish breeding farms for the biggest type of “city” horses.

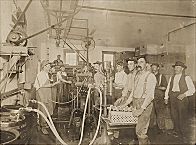

From 1860 to 1890, brewing underwent a profound scientific and technological revolution. Louis Pasteur's work on beer yeast identified germs and other microorganisms as the main reason why such a large proportion of the beer went bad. The virtually complete domination of the industry in Chicago by German immigrants and their offspring meant that the city became a leading center of “scientific brewing,” boasting a special school, the Siebel Institute of Technology. Successful businessmen such as Conrad Seipp, Peter Schoenhofen, Michael Brand, and Charles Wacker, giants in the brewing community, underwrote the inventions that helped bring refrigeration machines to a point of commercial practicality. They also replaced the traditional brewmeister with university-trained chemists. The malting business grew in tandem, branching off to form an important industry in its own right. Applying more and more energy in the form of heat, power, and cooling, beer making became one of the country's most highly automated and mechanized industries, complete with assembly lines in the bottling plant. By 1900, Chicago's 60 breweries were making over 100 million gallons a year.

At the same time, however, the half-century campaign for temperance was becoming a highly charged political issue, full of ethnocultural, gender, and class meaning. Concerns about new waves of European immigrants, women's changing roles, and working-class militancy fueled the attack on the neighborhood saloon as the city's greatest social evil. With the coming of World War I, the forces of reform won passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, marking the end of Chicago's role as a vibrant center of innovation. After the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the city's brewing industry did not recover in the face of competition from national brand names selling beer in cans. One by one, the city's breweries closed their doors.

Industrial beer making in Chicago languished until the 1980s. Attempts to reopen some of the old large-scale breweries ultimately failed, but microbreweries (small-scale brewing companies) and brewpubs (restaurants with attached breweries) kept the city's beer-making tradition alive.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.