| Entries |

| M |

|

Meatpacking

|

The preparation of beef and pork for human consumption has always been closely tied to livestock raising, technological change, government regulation, and urban market demand. From the Civil War until the 1920s Chicago was the country's largest meatpacking center and the acknowledged headquarters of the industry.

|

Americans took their cattle and hogs over the Appalachians after the Revolutionary War, and the volume of livestock in the Ohio River Valley increased rapidly. Cincinnati packers took advantage of this development and shipped barreled pork and lard throughout the valley and down the Mississippi River. They devised better methods to cure pork and used lard components to make soap and candles. By 1840 Cincinnati led all other cities in pork processing and proclaimed itself Porkopolis.

Chicago won that title during the Civil War. It was able to do so because most Midwestern farmers also raised livestock, and railroads tied Chicago to its Midwestern hinterland and to the large urban markets on the East Coast. In addition, Union army contracts for processed pork and live cattle supported packinghouses on the branches of the Chicago River and the railroad stockyards which shipped cattle. To alleviate the problem of driving cattle and hogs through city streets, the leading packers and railroads incorporated the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company in 1865 and built an innovative facility south of the city limits. Accessible to all railroads serving Chicago, the huge stockyard received 3 million cattle and hogs in 1870 and 12 million just 20 years later.

|

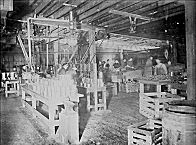

The extension of railroads and livestock raising to the Great Plains prompted the largest Chicago packing companies to build branch plants in Kansas City, Omaha, Sioux City, Wichita, Denver, Fort Worth, and elsewhere. To promote their dressed beef in eastern cities, they built branch sales offices and cold storage warehouses. When railroads balked at investing in refrigerator cars, they purchased their own and leased them to the railroads. Thus, Chicago's Big Three packers—Philip Armour, Gustavus Swift, and Nelson Morris—were in a position to influence livestock prices at one end of this complex industrial chain and the price of meat products at the other end. In 1900 the Chicago packinghouses employed 25,000 of the country's 68,000 packinghouse employees. The city's lead was narrower at the end of World War I, but Chicago was still, in Carl Sandburg's words, “Hog Butcher for the World.”

|

When the Armour, Swift, and Morris companies cooperated in a new National Packing Company and purchased some food-related firms, Charles Edward Russell warned about the existence of a “beef trust.” His book The Greatest Trust in the World (1905) caused the federal government to start antitrust proceedings. Although the courts failed to indict, the National Packing Company voluntarily dissolved in 1912. In the Packer Consent Decree of 1920, the Big Three agreed to sell their holdings in stockyards, food-related companies, cold-storage facilities, and the retail meat business.

The packers faced challenges from their employees. First organized by the Knights of Labor, packinghouse workers in Chicago struck for the eight-hour day in 1886, but public reaction to violence in Haymarket Square ended that strike. The Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor, made impressive gains in all the packing centers at the turn of the century. In the summer of 1904 this union led a long, bitter contest for wage increases. Some 50,000 packinghouse workers walked off their jobs. But in the end, only Jane Addams's intervention with J. Ogden Armour saved the strikers from total defeat. In response to renewed organizing during World War I and a demand for collective bargaining, President Woodrow Wilson established a federal arbitration process, and workers won temporary wage increases and the eight-hour day. When packers cut wages at the end of 1921, the Amalgamated called a strike which it soon rescinded. Thanks to the New Deal's pro-labor policies, Amalgamated membership revived in the 1930s and the Congress of Industrial Organizations launched a new packinghouse union. At the end of the decade, the large packing companies finally signed their first labor contracts. Postwar changes in the industry, however, minimized the impact of this victory.

Railroads centralized meatpacking in the latter half of the nineteenth century; trucks and highways decentralized it during the last half of the twentieth. Instead of selling mature animals to urban stockyards, livestock raisers sold young animals to commercial feedlots, and new packing plants arose in the vicinity. Unlike the compact, multistory buildings in Chicago, Kansas City, or Omaha, these new plants were sprawling one-story structures with power saws, mechanical knives, and the capacity to quick-freeze meat packaged in vacuum bags. Large refrigerator trucks carried the products over interstate highways to supermarkets. Many of the new plants were in states with right-to-work laws that hampered unionization. Business in the older railroad stockyards and city packinghouses declined sharply in the 1960s. Chicago's Union Stock Yard closed in 1970, the same year the Greyhound Corporation purchased Armour & Co.

At the end of the twentieth century, the meatpacking industry was widely dispersed but still under government regulation. Changing consumption patterns posed new challenges, as poultry and fish began to replace beef and pork in American diets.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.