|

Clothing, traditionally made at home or by custom tailors, began to be commercially produced in the early nineteenth century. In Chicago this industry developed rapidly after the Great

Fire of 1871

and remained one of the most dynamic sectors until the

Great Depression.

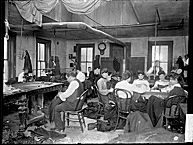

Garment Industry Sweatshop, 1905

|

Starting from the 1860s, the city's men's clothing merchants employed tailors and had ready-to-wear clothes made at their shop. The industry expanded in the next decade, as merchant-manufacturers like Harry Hart and Bernard Kuppenheimer produced suits as well as work clothes and marketed them in the Midwestern and Southern states. Those years also saw women's clothing production added to the industry, when manufacturers like Joseph Beifeld began producing ready-made cloaks. Chicago was increasingly involved in nationwide competition, which led to the sweating system in the 1880s. Manufacturers sent out

work

to be done by contractors and subcontractors, who often opened tiny shops in poor districts, the

Near West Side

in particular, and hired immigrants for long hours at low wages. In the early 1890s, urban reformers engaged in an anti-sweatshop campaign in Chicago and across the country.

Women's Garment Factories, 1925 (Map)

|

By that time, however, Chicago was already turning to the factory system. Trying to secure an edge against their New York and Philadelphia competitors, manufacturers began producing better grades of garment with fine material and workmanship. They established large factories, where each worker took up only one segment of the whole production process and dexterously performed it. They also endeavored to improve the public image of ready-made garments through national

advertising.

The pioneer in this arena was Joseph Schaffner of

Hart, Schaffner & Marx,

a Chicago firm that was to grow into a giant, employing 8,000 workers and leading the U.S. clothing industry in the early twentieth century. These efforts, aimed at the emerging urban middle classes, led to industrial expansion. By the end of the century, Chicago became the second largest production center for men's clothing, with its output roughly amounting to 15 percent of the national total. New York as the center of fashion dominated women's clothing, attracting numerous small shops and producing four-fifths of the national output. With only 4 percent of the women's market, Chicago concentrated on cloaks and suits and attempted to establish only a relatively few small factories.

Robbins with Garment Strikers, 1915

|

Although the factory system never entirely replaced sweating, it led to modern labor relations. Ethnic diversity particularly characterized Chicago's workforce, which included a significant number of

Swedes,

Czechs,

Poles,

and

Lithuanians,

in addition to

Jews

and

Italians.

The workforce remained further fragmented by gender and skill. Women constituted the majority on the shop floor but had little access to high-paying jobs. Cutters, mostly of

German

or

Irish

descent, despised tailors. Yet factories, mainly located close to immigrant settlements in the Northwest, Near West, or Southwest districts in addition to the

Loop,

helped workers cultivate close social networks and resort to collective action. In men's clothing, a general

strike

involving over 40,000 workers and lasting for 14 weeks in 1910–11 prompted the formation of a local union of immigrant workers. This organization, chartered by the United Garment Workers, helped launch the

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America

(ACWA) in 1914. Under the leadership of Sidney Hillman, the ACWA completely organized Chicago in 1919 and claimed a membership of 41,000 in the following year. The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) helped the small and unstable local women's clothing unions of the city to form a joint board in 1914. The joint board conducted unionization campaigns and soon secured a citywide agreement with employers. By 1920, the ILGWU claimed a membership of 6,000, two-thirds of Chicago's women's clothing workforce.

The mid-1920s turned out to be a high point. With a larger share of the national market than before and with labor relations stabilized through collective bargaining, Chicago's clothing industry was faced with new challenges. Men looked for lower-priced garments, spending more money on automobiles, radios, and other modern conveniences; women preferred the dress and waist to the coat and skirt, often wearing the suit. Manufacturers were less interested in technological

innovations

than in concessions to be made by the unions. When the ILGWU lost a major strike in 1924, the ACWA retreated without completely giving up high wage rates. Consequently, large men's clothing firms tried to maintain sales by integrating retail outlets, but small ones began to leave for nonunion towns in the Midwestern countryside.

By the late 1920s, Chicago's clothing industry was already on the decline, a tendency greatly accelerated by the

Great Depression.

The

New Deal

revived women's clothing; government contracts for military uniforms boosted men's; and postwar prosperity temporarily benefited both. Soon, however, manufacturers began to leave Chicago, many settling in the South, where labor expenses were lower. Lower production costs fit American preferences for spending less on clothing than on homes, home appliances, and automobiles, and for informal wear that accommodated increasing

leisure

time and the suburban lifestyle. Lower costs also made it easier to compete with imports, particularly those made in low-wage countries in Northeast Asia, which were taking an expanding share of the American market. By the mid-1970s, Chicago had only 7,000 workers engaged in the clothing industry. The few manufacturers still remaining in the city have attempted to integrate the making of men's and women's clothing and to experiment with new technologies like laser cutting or programmed sewing.

Youngsoo Bae

Bibliography

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. Research Department.

The Clothing Workers of Chicago, 1910–1922.

1922.

Carsel, Wilfred.

A History of the Chicago Ladies' Garment Workers' Union.

1940.

Cobrin, Harry A.

The Men's Clothing Industry: Colonial through Modern Times.

1970.

|