| Entries |

| A |

|

Agricultural Machinery Industry

|

|

On August 30, 1847, McCormick, in partnership with Charles M. Gray (later mayor of Chicago), bought three lots on the north bank of the Chicago River. The two immediately began construction of a factory to build the McCormick reaper. By 1850, with the McCormick factory in full operation, the U.S. census reported 646 people working in the agricultural implement industry in Chicago.

Chicago soon attracted other machinery producers, including George Easterly of Heart Prairie, Wisconsin, who built a Chicago factory to produce his grain header, and John S. Wright, who made a self-rake reaper developed by Jearum Atkins. But the sharp financial panic of October 1857 destroyed or crippled many of McCormick's competitors. In 1860, his factory occupied 110,000 square feet of floor space and, with more than 300 workers, employed nearly a fifth of all wage earners in Chicago's agricultural implement sector.

During the next decade employment in the sector grew quickly—the 1870 Census found nearly 4,000 working in agricultural machinery establishments—but the McCormick Company, though still the largest single employer in the Chicago implement industry, had stagnated. Its products were ill-suited to a shift among many farmers to combined machines that could efficiently harvest both grain and hay, the latter much in demand to feed the livestock in America's burgeoning cities. McCormick harvesters also technically lagged behind specialized self-rakes used for harvesting small grains. As a result, McCormick had shrunk to a regional firm, selling principally in upper Midwest states.

|

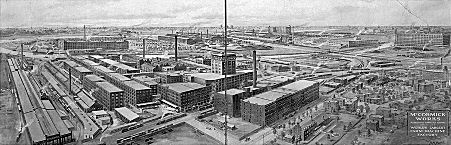

A few years earlier, William Deering, a retired merchant from Maine, had come to Plano, Illinois, to superintend another reaper factory his old friend William Gammon had purchased. Deering settled in Evanston the following year and, after buying control of the company in 1878, moved it to Chicago in 1880. The William Deering Company soon rivaled the leading McCormick Company, and the Deering factory on the North Branch of the Chicago River employed nearly as many workers as the McCormick plant on the South Branch. A second reaper company was organized to take over the old factory in Plano, but it too relocated to the Chicago area. In 1893, the Plano Company built a new factory in West Pullman.

In the mid-1880s, as McCormick management tried both to gain closer control over the production processes and to wrestle with the impact of a severe national recession, labor unrest grew rapidly. As a result, the McCormick Works faced several major strikes. During one, police used brutal tactics to defend nonunion workers from attacks by strikers as they left the plant on May 3, 1886, leading directly to the protest meeting the next night at Haymarket Square, a meeting at which a bomb killed seven policemen. Only a few years later, however, McCormick proudly went through the tumult surrounding the Pullman Strike with no troubles at all; by then the company paid among the highest factory wages in Chicago and enjoyed high worker loyalty.

In 1902, these three companies—McCormick, Deering, and Plano—together with two others, came together to form the International Harvester Company (Navistar after 1986). The new company controlled more than 80 percent of world production in grain harvesting equipment. International Harvester quickly expanded its Chicago-area facilities. At its peak, in the 1920s and 1930s, the company had six major manufacturing facilities in the Chicago area (plus a steel mill in South Chicago ), covering 440 acres, and accounting for a large share of the nearly 23,000 workers in Chicago's agricultural machinery sector in the 1930 census. This accounted for more than half the national total of 41,662.

This was the high-point of the industry in the Chicago area. The Great Depression took a heavy toll, and after World War II both International Harvester and the broader industry undertook all of its expansion outside the Chicago area. As a result, the Chicago-area plants were increasingly outdated and uneconomical. In the 1950s, the McCormick Works was progressively closed down, and the agricultural machinery industry no longer held a significant place in the Chicago-area economy.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.