| Entries |

| W |

|

Work Culture

|

|

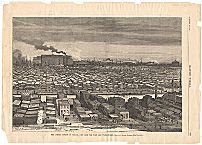

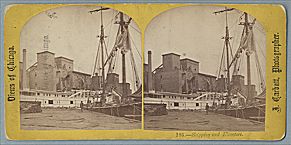

What Carrie saw was a remarkable diversity of opportunities shaped by the unique geography of the city. The centrality of Chicago to shipping and transportation routes by water and land made possible and profitable businesses of all kinds—and a correspondingly wide variety of workplaces. Carrie's brother-in-law Sven cleans refrigerator cars at the stockyards; her friend Drouet is a “drummer”—a traveling salesman; and his acquaintance Hurstwood is a well-to-do restaurant manager. Carrie finds her first job punching eyeholes into shoes at a factory on Van Buren street. Their choices within this cornucopia of employment possibilities were determined by a combination of gender, age, education, ethnicity, race, and marital status.

Work cultures, that mix of practices and ideologies arising from the interactions of people with their work environments, have been shaped in Chicago above all by diversity—diversity of employment opportunities, population, and housing. The ways in which people find jobs, the rhythms of employment and unemployment, the size of the workplace, the process of getting to and from work, how the workday is organized, power relationships and hierarchies, how workers learn and manage their tasks, how they socialize and organize family life, how informal worker behavior interacts with sanctioned authority and rules—all these things constitute work culture. There are many different work cultures, reflecting the differences between skilled and unskilled labor, professional, white-collar, and service work, and workers' identities by race, gender, age, and ethnicity. Work cultures have also changed as the nature of work has transformed over the past 150 years.

|

Throughout the nineteenth century, work for a huge pool of floating and unorganized labor was shaped by transience. The reliance on the products of nature for profit— agriculture, livestock, ice, and lumber —required men to move according to the rhythms of the seasons. They planted in the spring, harvested crops or timber in the fall, cut ice in the winter, and shepherded cattle and pigs through increasingly narrow roads into the city for processing and sale. Uncontrollable forces like drought or fire could instantly create or destroy opportunities for employment.

Transient laborers tended to be white, unmarried men. Answerable to a gang boss, men would work for a season, collect their pay, and move on to the next opportunity. This was not usually a life for families. Transient laborers often lived in cheap boardinghouses, able to pick up and follow work wherever it appeared.

|

The nature of work in shops was very different. Through the early decades of the nineteenth century, workshops were small, with craftsmen hiring a few skilled handicraft workers at a time. Apprenticeship and later employment were personalized and individualized, as cabinetmakers, upholsterers, machinists, and others created items from design to finished product.

|

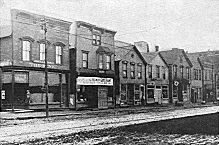

The growing demand for labor coincided with the influx of immigrants. Reflecting national patterns, the first waves of foreign immigrants to Chicago in the 1850s and 1860s included Irish, German, and Scandinavian newcomers. From the 1870s through the beginning of the twentieth century, people from Eastern and Southern Europe—Bohemians, Lithuanians, Italians, Russians, Greeks, Hungarians, Austrians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews —flooded into Chicago looking for opportunity and work. Often unskilled and with limited English, these workers found work in the giant factories, particularly in the stockyards, ironworks, and steel industries. Chinese came in lesser numbers and looked especially to laundries as opportunities for self-employment. By the 1890s, three out of four Chicagoans were either immigrants or the children of immigrants.

|

From the South during the 1890s came the first significant numbers of African Americans. A majority of these black migrants, barred from higher-paying factory jobs, found work in domestic service or day labor. As industrial labor opened during the 1910s, the Great Migration from the South would bring thousands more blacks and establish the city as a leading center of African American life.

|

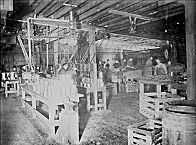

The plant foreman set the daily pace. His authority was absolute. He could raise or decrease the speed of work, determine pay, and assign hours and tasks of labor. He represented factory management to the operatives under his command and had the power to hire and fire at will. For his workers, the workday offered very little autonomy or sense of empowerment.

|

The cost of this unregulated industrial growth included the pollution of home and workplace. Workers labored long hours in unsafe conditions, sometimes standing all day in noisy, crowded, filthy, overheated and unventilated rooms, always with the threat of dire poverty should injury or illness or unemployment stop a paycheck. There was no safety net.

|

|

Racial segregation kept the relatively few black factory workers in more distant parts of the city, forcing them to find daily transportation to and from their work and blocking channels of social interaction that might have reduced racial barriers. Until 1916 black factory workers were few and far between, though some did find employment on the killing floors of the stockyards or in the steel mills. More commonly, black men worked as unskilled day laborers, restaurant waiters, Pullman porters, bootblacks, and hotel redcaps, while black women filled the laundry trades and other forms of domestic service. Like industrial workers, unskilled laborers and service workers faced uncertain job security, as slack times led to staff reductions with no notice. Moreover, black employees of hotels, restaurants, and the railroads found themselves employed in places which would deny them and their families and neighbors service as customers.

White and educated native-born men more easily found employment possibilities in business and the professions. By the 1950s, studies of such new postwar suburbs as Chicago's Park Forest suggested that the culture of white-collar work for men had transformed. The workplaces of large corporations in business, government, and industry were staffed by bureaucratic “organization men” who evidenced a “group-mindedness” characterized by values of security and safety rather than initiative and risk. They identified their well-being with that of the company, and so long hours at work, and the belief that the company would reward loyalty with lifetime employment, fostered an environment of conformity that marginalized individual initiative and creativity.

|

Native-born white women also found opportunities in emerging occupations, such as the professional fields of education and librarianship and the white-collar areas of clerical and department store work. Wages were consistently lower for women than for men, and unionization far less frequent.

|

As the great urban department stores like Marshall Field's appeared during the second half of the nineteenth century, department store sales work also became a woman's profession. Managers trained “shopgirls” to become “professional” saleswomen skilled in everything from etiquette to merchandise. At Marshall Field's a personnel department was described as “a conscientious mother” working to influence the workers in the niceties of behavior and saleswomanship. Managing the business was a large-scale enterprise; by 1904, the workforce at Marshall Field's could reach 10,000 in a store which served up to a quarter of a million customers a day.

The work culture of this particular occupational group developed to express three identities of the saleswoman: worker, woman, and consumer. These identities, reflected through a set of unwritten rules followed on the job, illustrated the complexities of women's lives where private and public identities intersected. The interactions among managers, saleswomen, and customers—which favored skills of social interactions and initiatives—allowed these retail workers a relatively autonomous working environment.

Many of these workers were called “women adrift”—the term for unmarried women living outside of traditional family life before the 1930s. They created a kind of “working girls” subculture in the city, challenging Victorian prescriptions for behavior, influencing popular culture, and ultimately changing social mores. This heterogeneous group of women—young and old, black and white, native-born and immigrant—lived in boardinghouses, both supervised and unsupervised, and later in apartments and furnished rooms. They patronized restaurants, dance halls, and theaters. This population of workers was sharply delineated by race; boarding homes, for example, were often segregated, as were working girls' clubs. For example, in Chicago the Eleanor Clubs served white women, while the Phyllis Wheatley Home had a black clientele.

For most married women, the ideal was a one-wage-earner family economy. For middle-class women—both black and white—voluntary participation in civic culture through organizations like church, women's clubs, and school organizations like the Parent-Teacher Association constituted a kind of unpaid work which contributed to the community environment. Additionally, the housekeeping and child care they provided constituted unpaid labor for their families, although many through the 1920s relied on domestic servants as they organized household work.

More often, however, a man's salary was insufficient to support his family. Women often supplemented family income by such “off the books” homework as midwifery, keeping boarders and lodgers, doing laundry, selling goods door to door, or by manufacturing garments or other goods at home. Hilda Polacheck, for example, describes how women and children labored around kitchen tables in crowded West Side tenements to make cloth flowers for women's hats during the late 1890s.

|

With the advent of the twentieth century, industrial work culture began to change. Scientific management came to many big corporations, such as the Pullman Palace Car Company, where from 1913 to 1919 efficiency experts brought modern techniques of manufacturing to the shop floor. As the century progressed, new standards of technology and factory organization greatly reduced the need for physical labor in the plants. Women and black men began to work in factories previously barred to them, although the type of work available was often still segregated by race and gender.

|

Further decline of industrial manufactures occurred in the later twentieth century, as professional, technical, and service industry occupations increased. The growth of multinational corporations meant that many more professional and white-collar workers now found that job security and work definitions could be determined by distant executives from abroad instead of by a local foreman or manager; health care workers saw the rise of Health Maintenance Organizations in the last two decades of the century change the nature of even professional workers' autonomy and decision-making power.

Additionally, the population of workers transformed. New immigrants arrived from Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Central America, Asia, and Africa. Child labor by the 1940s was no longer as accepted as it was earlier because of new legal requirements for longer schooling as well as changing cultural conceptions of childhood. Even more significantly, during the second half of the twentieth century the labor force participation rates for women in every age group under 65 increased, especially as married women began to work at higher rates. As more married women and mothers of young children entered the workforce, debates about policies on child care, extended school hours, and such conditions of work as flextime were raised across a variety of occupations.

Since Chicago's earliest years as a fur trading outpost on the Midwestern prairie, the city's work culture has reflected the tremendous diversity of its people and its economy. Strongly shaped by geography and characterized by a remarkably varied population, Chicago's story has been no less than the larger saga of American economic and social development—continually changing and reflecting complex interactions between people and their workplaces. If the industrial city witnessed by Carrie Meeber at the end of the nineteenth century has vanished, still new forms of work and work culture have developed which just as surely shape the lives of Chicagoans and reflect the continuing evolution of the city itself.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.