| Entries |

| R |

|

Religious Geography

|

Wherever people have settled in metropolitan Chicago, they have built churches and synagogues, and eventually mosques, gurdwaras, and temples, of the various religions of the world. From their many countries of origin and from regions within the United States, they have brought diverse architectural styles, builders with unique technical skills, and sometimes even the building materials with which to recreate cultural forms expressing not only their religions but multiple dimensions of their heritage, including ethnicity, nation, region, race, and class.

|

Early Settlements

The effort to define one denomination's “religious space” began as early as Father Marquette's appointment as the first priest to the Illinois mission in 1673. Persistent contacts between Roman Catholics and Native Americans continued down to the incorporation of Chicago in 1833. The first Baptist sermon was preached in 1825, and by 1830 the Methodists had created the Chicago Mission District. Of the congregations still in existence today, the first to be organized was First Methodist Church, which met for the first time in 1831 and built its first building in 1834. St. Mary's Catholic Church was organized in 1833 and erected a structure a few years later. By the middle of the century, Chicago's public square was flanked by five edifices (four Protestant and one Unitarian), whose size and imposing design represented religion's active presence in the public and commercial life of the young city. An equal number of churches, including Catholic St. Mary's, were built in the few blocks between the public square and Lake Michigan, and St. Peter and St. Patrick Catholic churches had been built in the western portions of the central area. The first Jewish congregation, Kehilath Anshe Mayriv, organized in 1847, met in space above Jewish-owned stores until 1851, when the congregation dedicated its first synagogue just three blocks south of the public square and its constellation of Protestant churches.

Most of the largest and most prestigious congregations in the civic and commercial center of the city succumbed to the escalating property values in the center and to the attraction of the new and prosperous residential areas nearby. Within 10 years of being built, all the churches on the public square except First Methodist (which remains on its site today) sold their properties and rebuilt in the fashionable residential areas along Lake Michigan south of the business center. Other churches abandoned their downtown locations for quieter areas west and north, notably St. James Episcopal Church and Holy Name Catholic Church, both of which moved north of the Chicago River, where large churches were built as the seats of their respective dioceses. This movement outward from the commercial district to residential areas presaged a pattern of locating congregations in residential rather than commercial or public areas, geographically expressing the association of religion with private more than with public life.

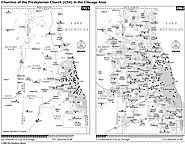

While the congregations meeting at the center of Chicago represented the greatest concentration of churches, Protestant and Catholic churches followed the expansion of residential areas away from the central business district. A notable German and Irish Catholic and German and Norwegian Lutheran presence was felt in the years before the Chicago Fire—the predominantly German Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod was founded in Chicago in 1847—and heralded an increasing association of religion and ethnicity in the years to come. At the same time, Protestants and Catholics gathered and built churches in small farming villages, trading settlements, and open country scattered around what is now the metropolitan region. Of the 54 Roman Catholic parishes founded before the Chicago Fire of 1871, 37 were outside the city boundaries, though a few of these were in areas that would become Chicago neighborhoods through annexation in 1889. Not to be outdone, Methodist circuit-riding preachers, Lutheran pastors, and Congregational missionaries founded churches in settlements along the waterways, trails, and eventually rail lines that connected Chicago with its hinterland.

Early Industrial Expansion, 1870–1930

|

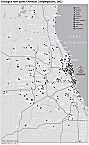

Because population growth was based on immigration and migration more than fertility, Chicago's religious geography reflected the patterns of settlement of its newcomers. Language and culture drew many of these newcomers together in ethnic neighborhoods, while racism and restrictive covenants ensured that African Americans and many Jews would live and worship in ghettoes. National parishes—permitted if not encouraged by the leadership of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese until 1918—anchored communities of Germans along the North Branch of the Chicago River, Irish west and south of the commercial district, and Poles in the southeast near the steel mills, southwest near the stockyards, and northwest along the Avondale industrial corridor. As these and other nationality groups rose to better-paying jobs, they built homes and churches further out. Protestants followed a similar pattern. German Lutherans often shared neighborhoods with German Catholics and built churches nearby. Immigrants from fiercely Protestant countries settled in neighborhoods defined by country of origin, such as the Swedish “ Andersonville ” several miles north of the city center, and built clusters of churches specific to their country, such as Swedish Lutheran, Swedish Methodist, and Swedish Evangelical Covenant. Thus churches, synagogues, parochial schools, and hospitals gave meaning and identity to places that were to make Chicago (like many other municipalities) a “city of neighborhoods.”

Some of these neighborhoods were ghettoes. While many of the earliest Jewish settlers, mostly from Germany, were successful in business and able to live in the more comfortable neighborhoods near Lake Michigan, this was not the case with those who later fled the pogroms of Russian and Eastern Europe and provided cheap labor for Chicago's burgeoning industrial economy. By 1910, what Chicago School sociologists called the Maxwell Street Ghetto just southwest of the commercial district, close to factories and shipping centers on the Chicago River, was the site of more than 45 shuls (synagogues) and an elaborate infrastructure needed for religious observance of the 40,000 or more residents. However, after World War I, most of these residents and synagogues moved to the North Lawndale neighborhood, five miles west; a few pioneered into Rogers Park, Albany Park, and Logan Square and established congregations and other Jewish institutions there.

African American migration from the South slowly began to accelerate in the final decade of the nineteenth century. Excluded from most neighborhoods, black Chicagoans crammed into a narrow “ Black Belt ” extending south from the commercial district along State Street. By 1912 they had established 28 churches of nationally recognized denominations and an unknown number of independent congregations. The Great Migration, beginning in 1916, brought even greater numbers, and by 1920 the black population had surpassed 100,000. By 1928 their churches—still mostly in the Black Belt—numbered at least 295. African American churches, most of which were located in an area five miles long and four blocks wide, accounted for some 20 percent of all churches in the entire Chicago region.

Industrial Consolidation, 1930–1960s

The geography of Chicago's religions continued to be shaped by developments in the industrial economy. Industrial jobs increased by more than 50 percent from 1929 to 1946, but these were concentrated in a roughly constant number of firms, mostly in South Side industrial districts served by ports and railroads (although the advent of air transportation and the development of Midway Airport supported employment in light manufacturing in the western parts of the city and suburbs). The population of the city proper peaked in the early 1950s, but the suburbs continued to grow as the affordable automobile made it increasingly convenient to live there. The number of city churches increased only slightly, while the number of suburban churches grew rapidly.

The small change in the number and location of city church buildings, however, belied the profound change in the race, class, and religious denomination of the people worshiping in many of those buildings. Perhaps most dramatically, the Black Belt overflowed its boundaries as black migration continued, and black Chicagoans moved into the “Second Ghetto” of large-scale public housing projects, as well as other rental units and modest bungalows, in parts of the South and West Sides of the city previously restricted to whites. By the 1960s, black churches could be found throughout much of the South Side and West Side, often occupying buildings previously owned by white congregations. In the process commonly known as “white flight,” or to sociologists as “ neighborhood succession, ” these white congregations moved with their members, either to other parts of Chicago, notably to the legendarily “white ethnic” Southwest Side and to the “Polish Corridor” of the Northwest Side, or to suburbs. The churches of the city were still tied to nearby industrial work opportunities for their members, but more and more of those members were minorities. By the same token, the growth of suburban churches reflects not only the “suburbanization of employment” but also the migration of white city dwellers from racially changing neighborhoods.

Large numbers of Jews also moved from racially changing neighborhoods as African Americans moved into Chicago's South and West Side neighborhoods during the 1950s and 1960s. Most dramatically, virtually all of the 110,000 Jews had left the Lawndale– Garfield Park area by 1970, and all of the synagogues had either closed or moved to other neighborhoods or suburbs. Unlike their Protestant counterparts who scattered across suburbia, Jews clustered in a few North Side neighborhoods and suburbs, mainly to avoid the anti-Semitic sentiment prevalent in many areas and to build the infrastructure needed for the full observance of halachah ( Jewish law). Particularly in the Albany Park, Rogers Park, and West Ridge neighborhoods and in suburban Skokie, Lincolnwood, and Buffalo Grove, enough observant Jews settled to support not only Kosher groceries and restaurants but numerous Hebrew schools and such institutions as the beth din ( Jewish court), the mikva (ritual bath), and social service agencies that strictly observe halachah. At the same time, more assimilated, liberal, and secular Jews were settling in comfortable lakefront neighborhoods and in some of the most affluent suburbs both north and south of Chicago.

|

Religion and Post-Industrial Sprawl, 1960s–2002

|

|

The economic attractions (not only jobs, but the new, low-density housing stock, the schools, and the automobile-based shopping) that drew Asian immigrants also appealed to American-born city dwellers, escalating the deconcentration of the city population and the sprawl beyond the city limits. Jews continued their suburban exodus, leaving only a few Reform and Conservative congregations in the city, and one area (West Rogers Park) with enough Orthodox Jews to sustain a complete halachic infrastructure. The suburban Jewish population grew with the suburbs north and northwest of Chicago, and, while most migrants have been Reform, Conservative, or secular, the suburb of Buffalo Grove, some 30 miles northwest of the city, has attracted enough Orthodox to sustain an institutional infrastructure for halachic observance. Nevertheless, while a few Jewish congregations have prospered in suburbs south of the city, the rapidly growing DuPage County west of the city entered the twenty-first century with a population approaching one million, but only two synagogues.

Catholicism's growth in the Chicago suburbs, based partly on migration from city neighborhoods, has often taken the form of expansion of existing parishes, many of which had been established when present-day suburbs were rural villages. Although new suburban parishes have been formed since World War II, the expansion of suburban Catholicism tends to take the form of increased size rather than numbers of parishes. Moreover, the ranks of city Catholics have been replenished by the arrival of a half-million immigrants from Mexico, Poland, Ireland, and other predominantly Catholic countries. As of late 2002, the archdiocese counted 2.4 million adherents (36 percent of them Hispanic) in the 374 parishes of Lake and Cook Counties.

Much as Catholicism had dominated most neighborhoods of the early industrial workforce, so Protestantism had been the hegemonic faith in the streetcar suburbs and in the suburban expansion following World War II. The addition of Protestant churches as more and more farmland succumbed to commercial and residential expansion was thus a continuation of an old story; the novelty lay in sharing the suburban terrain with a growing Catholic church, with Jews, and with adherents to the many religions of the world.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.