| Entries |

| S |

|

Social Services

|

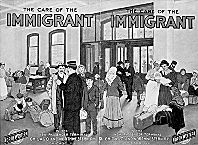

The term “social service” (or social welfare) refers to the variety of programs made available by public or private agencies to individuals and families who need special assistance. Prior to the 1920s, Americans referred to these services as charity or relief, but they covered a wide range of services, including legal aid, immigrant assistance, and travelers' aid. The new terminology corresponded to changes in the philosophy, approach, and organization of social work.

|

|

The Great Depression's economic crises led to a shift in Americans' ideas about government responsibility for economic security. The New Deal infused federal funds into programs that affected banks as well as farmers, investors, and industrial workers. The Social Security Act of 1935 created a federal system of provision for the aged, unemployed, and categorically poor, funded by an employees' contributory tax. The U.S. social insurance system divided benefits between entitlements to workers in covered jobs and categorical aid (welfare) to those in uncovered sectors or unable to work. States retained considerable control over the expenditure of funds and administration of services for the categorical welfare programs. Historians generally agree that the infusion of federal funds through the New Deal programs averted a prolonged economic decline but did not pull the country out of the Depression. That credit goes to the war industry jobs that started at the end of the 1930s and in the first years of the 1940s.

The federal government continued to promote economic and social stability for a wide range of Americans following World War II. Employment policies for returning veterans, low mortgage interest rates, and subsidies for national highways contributed to the era's economic expansion. Cold War politics provided a new rationale for civil rights laws and economic opportunity policies. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson cultivated this approach most specifically with their education and antipoverty programs. Like the programs that proceeded them, the new services sought to ameliorate social problems created in part by economic and social inequality.

Chicago's development of social services fits prominently within the larger national trends. Public and private charities contributed to Chicago's early social services, but the private societies held the dominant role until Progressive-era programs altered the balance. Chicago's oldest and largest private charity, the Chicago Relief and Aid Society (CRAS), founded in 1857, considered its mission to assist the “worthy poor.” That service base broadened by necessity when the 1871 fire destroyed many homes and left thousands helpless. The city of Chicago selected this established group to distribute approximately $5 million in donations, but it appeared that the CRAS might lose its autonomy in the push to coordinate the delivery of services. The concern revived in 1887 when the CRAS annexed Chicago's first charity organization society, but it managed to retain its autonomy by resisting efforts by charity organization societies to coordinate resources and investigate charity cases.

Chicago's social services comprised both public and private resources at the turn of the twentieth century. Public facilities included the Cook County Hospital, the Juvenile Court, the Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium, the County Agent's Poor Relief Department, and the Dunning institutions (among them the poorhouse). Most of the poorhouse residents came from the ranks of the aged, the seasonally employed, and single mothers with young children. District poor relief offices dispensed “outdoor relief” to the desperately destitute in the form of bags of coal, baskets of groceries, and infrequent stipends. During severe economic downturns, the city of Chicago opened temporary boardinghouses for unemployed men. These usually had auxiliary “employment bureaus” and wood yards where boarders worked off their stay.

Privately organized agencies provided a multitude of other services, such as homes for the aged, unwed mothers, orphans, working girls, and abandoned or dependent children. Child health services, kindergartens, and day nurseries received their earliest support from private organizations. However, the majority of private charities provided services only to a specific religious or ethnic group.

Proponents of a reformed and coordinated system of social services, including Jane Addams ( Hull House settlement), Lucy Flower (Chicago Woman's Club), Charles Henderson (professor of sociology, University of Chicago ), Julia Lathrop (first director of the U.S. Children's Bureau), and Julius Rosenwald (philanthropist) worked with others to found a new organization called the Central Relief Association, renamed the Bureau of Charities in 1894. This association took charge of relief efforts during the depression of 1893 and had 10 districts with 800 friendly visitors providing services in Chicago by 1897. In addition to a register of clients for better-coordinated services, the bureau broadened those it served through programs such as day nurseries, lending libraries, dental dispensaries, kindergartens, and a loan fund. In 1909, the Bureau of Charities joined with the Relief and Aid Society to form the United Charities of Chicago.

Between the 1890s and 1930, new ideas about the cause of poverty changed the substance and structure of social services in Chicago. Private and public charities continued to serve selective populations, but support for a wider range of publicly funded social programs gained prominence nationally and locally. The city's universities and settlement houses formed the heart of the new initiatives. Charles Henderson led early investigations with his University of Chicago sociology students. He collaborated in social research projects with Graham Taylor at Chicago Commons, Mary McDowell at University of Chicago Settlement, and Jane Addams at Hull House. New methods of social investigation such as social surveys and statistical analysis produced new explanations for the causes of poverty, as social researchers investigated the relationships between environment, family structure, and local politics on one's chances for economic and social opportunity. Although elite ideals of noblesse oblige and beliefs in individual failing as the cause of poverty would still remain, they competed in a new environment.

Some participants recognized the limits of the charity ideal of self-help after taking part in social investigations. Lathrop's research on county public charities for an 1893 federal study of urban slums led her to criticize sharply the county's poor relief office. Robert Hunter, another resident of Hull House, wrote Poverty, his treatise on the structural dynamics of economics, in 1904, shortly after his tenure as the organizational secretary for Chicago's Board of Charities.

The systematic analysis of social issues demanded specialized training for social workers. Settlement leaders believed that a coordinated course of study that involved students in methods of social investigation offered a significant improvement over the irregular training of settlement workers, friendly visitors, and poor relief investigators. Reformers from the settlements and the community joined with academics at the University of Chicago to develop a program of study in social work. Taylor gave the first series of lectures as early as 1895. The program expanded rapidly when Henderson, Lathrop, and Hunter also contributed lectures. Within a few years, students could take a program in social research at the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy. The school's Department of Social Investigation directed by Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge, conducted the earliest social investigations of the Juvenile Court and trained African American social workers through the Wendell Phillips settlement. The School of Civics and Philanthropy joined the University of Chicago as the School of Social Service Administration in 1920 and continued the tradition of using scientific research to inform social work practice.

The justification for social provision began to change as well. One component of progressive reform sought to use state authority to decentralize the economic power of monopolies and to create greater access for Americans to the economic and social benefits of democratic capitalism. This created an opening for those reformers who wanted to expand individual rights to include government responsibility for and protection of citizens, specifically workers, immigrants, women, African Americans, and children. Reforms such as protective labor legislation, mothers' pensions, and child labor laws came out of this context and had early successes in Illinois because of the effective leadership of Chicago reformers.

African American residents of Chicago used public social services to the extent possible, but de facto residential segregation and pervasive racism remained a persistent obstacle. The African American community created numerous institutions to serve individual and family needs. Of dozens of local programs, the best funded were Provident Hospital, the Urban League, and the YMCA. The Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass settlement houses offered community services within their neighborhoods as well as social work training. Ida B. Wells founded the Negro Fellowship League in 1910 as a resource for young men. A network of women's clubs, churches, and mutual aid societies raised funds for the Phyllis Wheatley Home, day nurseries, and homes for dependent children. However, the community's difficulty securing funds eventually made it difficult to maintain community control. The Urban League, formed in 1916, provided the first coordinated services to African Americans in Chicago and began to involve white philanthropists like Julius Rosenwald in the support of programs. The organization identified itself as a vehicle to create opportunities (usually meaning self-help through employment) for men and women and distanced itself from any charitable activity.

One significant result of the new directions taken in social services during the Progressive era can be found in the expansion of the public infrastructure for services. Chicago's initiation of a juvenile court in 1899—the first in the nation—offered an early example of the changes ahead. The Chicago Woman's Club drafted a juvenile court law in 1895, but questions of constitutionality stalled it before it reached the legislature. By 1898, a coalition of women's clubs, charities, lawyers, and child welfare advocates submitted a new bill and saw it through the legislature. In 1911, the court system expanded again to accommodate two new programs, for mother-only families. The Cook County Municipal Court opened a new Court of Domestic Relations. Two-thirds of the cases heard involved abandonment and nonsupport of women and children. The court defined its purpose as a clearinghouse to receive complaints, find responsible parties, retrieve and disburse support funds, and refer families to appropriate agencies. The Juvenile Court also initiated a new branch to administer the new mothers' pension law that year. The court's judge recognized the social service aspects of the law and included representatives of the social work community in the organizational plan. The mothers' pension division had its own director, investigators, and staff.

The era's changes led to a greater degree of planned and coordinated services. Several Chicago agencies had been associated with the state conference of Charities and Corrections since the 1890s, but the degree of expansion and change created additional layers of collaboration at the local level. In 1914 the Chicago City Council approved the creation of a Department of Public Welfare to conduct social research. The Welfare Council of Metropolitan Chicago, formerly the Chicago Council of Social Agencies, founded in 1914 by representatives of public and private agencies to anticipate needed reforms and coordinate research on issues, served as the liaison between local government, business, and philanthropic communities.

By the late 1920s, signs of economic dislocation appeared among Chicago's most vulnerable workers. Layoffs, first experienced by African Americans and Mexican Americans, increased the demand for temporary relief services. Unemployed transient men once again drew attention to the need for lodging houses. Although Chicago's settlements continued to provide social services to their neighbors, Hull House and Chicago Commons adapted their services to address also the needs of Mexican Americans and African Americans, whose numbers increased in the city during the 1920s and 1930s. During the winter of 1932–33, approximately 40 percent of the labor force in Chicago had no work. The network of public and private agencies tried to respond, but local efforts in Chicago were overwhelmed by demand. By 1933, federal public works programs started to mitigate the crisis by employing the unemployed on building projects. This infusion of federal funds staved off a deeper depression.

The influence of individual Chicagoans in Progressive-era social services and planning extended over several decades and beyond city and state borders. The economic crises of the 1930s and the expansion of the federal bureaucracy with New Deal programs brought many Chicago reformers to Washington DC. Charles Merriam began the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) shortly after his failed 1919 mayoral campaign. The SSRC organized the Commission on Recent Social Trends with the intent to design a national plan for development. The Depression and Franklin Delano Roosevelt's defeat of Herbert Hoover derailed Merriam's strategy, but only temporarily. Merriam's campaign manager for the Chicago mayoral race, Harold Ickes, became Roosevelt's secretary of the interior. He appointed Merriam to the National Planning Board. More specific to social services, Chicago reformers served on committees that would write the Social Security Act. Grace Abbott, past director of the U.S. Children's Bureau, served on the Advisory Council to the Committee on Economic Security and developed the child welfare provisions. Edith Abbott served on the advisory committee on public employment and public assistance.

The postwar economy created greater prosperity in employment and consumption for many Americans, and Chicago continued to attract those seeking work. It was a major destination for African Americans who left the South during and after the war as well as Mexican Americans who had begun migrating to Chicago in substantial numbers during 1920s. However, the expansion left behind many Americans. The elderly, mother-only families, the chronically ill, and racial minorities had disproportionate rates of poverty. Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society programs focused on creating equality of opportunity through federal initiatives in health, education, and welfare. Programs for the aged, including Medicare, created a powerful “senior” lobby and made this component of the welfare state difficult to challenge. In contrast to the popularity of Medicare, the War on Poverty programs that intended to improve education, employment, housing, and health care in areas of concentrated poverty received a hostile reception from voters and local politicians.

Chicago's experience with Great Society programs varied. Politicians gladly accepted the federal funding attached to employment, housing, and model cities programs without sharing in the greater social goals to create opportunities for economic mobility. But federal officials never developed the state and local support of elected officials necessary for the successful implementation of programs. At the end of the twentieth century, new social problems emerged as a result of transitions in the postindustrial economy, stagnant or declining wages, drug trafficking, and a health care system in crisis. At the time that the country needed new solutions for these crises, support for government spending on social services declined precipitously and voluntarism increasingly filled the gap. The election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency in 1980 signaled a national groundswell of support for limited government spending and a turn away from the previous two decades of enlarged social programs. No political entity escaped these efforts to dismantle the welfare state. In Chicago and elsewhere, cutbacks in public funding resulted in a decline in some services and programs, an increase in nonprofit provision of services and in philanthropy, and greater state and local decision-making on the use of federal matching funds. The public and private collaboration that defined social services at the beginning of the century continued at the end of the century, as local governments contracted with private agencies to support numerous social services.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.