| Entries |

| B |

|

Blues

|

As legendary guitarist Robert Johnson put it, Chicago has been a “sweet home” for the blues. The most recognizable cultural signature this city has produced, Chicago blues has diverse and contradictory roots: African American migration from the South and the growth of the modern music industry; regional folk genius and ethnic entrepreneurial savvy. This rich sense of origin and history makes blues music such a celebrated civic resource, one that still shapes cultural and social practice throughout the Windy City.

|

|

During the 1950s, Chicago blues flourished, developing the signatures—use of rhythm sections and amplification; reliance on guitar and harmonica leads; and routine reference to Mississippi Delta styles of playing and singing—that identify it today. Consolidation of blues recording continued, with new labels Chess, Vee-Jay, and Cobra all signing and producing large numbers of artists. Of these, the most prominent was Chess, whose first generation of artists—Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield), Little Walter ( Jacobs), Willie Dixon, Howlin' Wolf (Chester Burnett)—were exemplars of Chicago blues style. The distinctive sound of these artists restructured popular music, providing fundamental elements for subsequent genres like soul and rock and roll. Indeed, the work of Waters on songs like “Rollin' Stone” (1950) and “Hootchie Cootchie Man” (1954) had international influence, subsequently inspiring the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other British bands. Dixon was also a figure of special note—in addition to playing bass and writing for artists ranging from Waters to Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, he supervised most of the studio sessions at Chess beginning in the mid-1950s.

A key catalyst to the blues' postwar popularization were “black-appeal” disc jockeys, such as Al Benson and Big Bill Hill, who ensured that records released by Chess, Vee-Jay, and other labels received public exposure. By the late 1950s and early 1960s a new generation of West Side artists, including Otis Rush, Magic Sam (Maghett), and Buddy (George) Guy, carried the work of Waters, Dixon, and other Chess artists even further. Chicago blues soon attracted substantially broader audiences. In 1959, Dixon and Memphis Slim toured England and the Middle East: they would return to Europe in 1962 with a full roster of artists to perform in the first of many annual American Folk Blues Festivals.

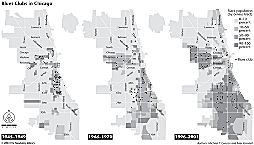

The history of Chicago blues since the 1960s has been a contradictory one, combining periods of recession and renewal. By the end of the 1960s, blues had infrastructural as well as aesthetic presence. WVON, the all-day radio station opened by Chess owners Leonard and Phil Chess in 1963, maintained a healthy blues playlist, augmenting programming from other local stations. Blues nightclubs continued to shape black neighborhoods on the South and West Sides; Roosevelt Road, Madison Street, and 43rd Street became blues thoroughfares. With the failure of Cobra Records in 1959 and Vee-Jay in 1966, Chess stood as the only remaining major label and, under the supervision of Willie Dixon, consolidated the remaining talent. Old rivals such as Buddy Guy and Otis Rush were signed, along with newcomers Etta James, Little Milton (Campbell), and Koko Taylor. Yet blues music found itself at a disadvantage commercially next to soul, gospel, and other new genres of black popular music. Chess went out of business in 1975, by which time most older clubs were closing down.

While Chicago blues did not recapture its centrality to the civic life of the African American community, a renaissance has been building since the late 1960s, when blues found a new audience drawn from followers of rock music searching out roots artists. Such local labels as Delmark, which recorded Junior Wells (Amos Blakemore) and Magic Sam (Sam Maghett), and Alligator, which recorded Koko Taylor and Lonnie Brooks (Lee Baker, Jr.), built a new national audience for Chicago blues. Old-line clubs (notably the Checkerboard) on the South and West Sides have been joined by new venues on the South, West, and North Sides (notably Kingston Mines) serving the tourist industry and predominantly white fans of blues. In 1984 Chicago inaugurated an annual blues festival. Continued participation in Chicago blues culture underscores that, as in earlier times, the music serves as “living history,” shaping both memories of and hopes for urban social life.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.