| Entries |

| W |

|

Waterfront

|

|

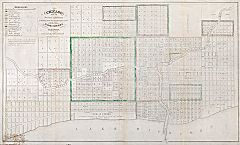

Chicago's position on a mid-continental divide between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River systems facilitated the city's early economic growth.

Early developments reflected the massive industrial growth of the city, and Chicago's waterfront was primarily devoted to commerce and industry. Near the end of the nineteenth century, concerns over cleaner water and environments and changing industrial patterns marked a move toward increased leisure use of Chicago's waterways. By the close of the twentieth century, the shores of Lake Michigan and those of the river systems had become less polluted, providing increased recreational opportunities.

In the early part of the nineteenth century, Chicago's riverine waterways flowed relatively clear, encouraging leisure pursuits such as fishing, swimming, hunting, walking along the waterfront, and boating. By midcentury, however, people interested in such activities needed to travel away from the city center and the polluted Chicago River, whose use as Chicago's harbor and primary industrial site exacted a devastating toll.

|

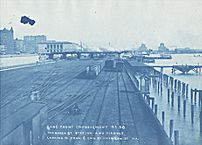

Just prior to the fire, the city began to create its large park system with plans that included modifications to the lakefront. Professional baseball was played adjacent to the lake near Michigan Avenue and Randolph Street. To the south, at Adams Street, the Inter-State Industrial Exposition of 1873 featured a Crystal Palace–styled building that hosted annual fairs, conventions, and other forms of entertainment over the next two decades. The building defined the lakefront as a cultural center and presaged the city's lakefront fairs. During those years, sailing attracted recreational craft onto the lake at the new yacht clubs and harbors along the shores of Lake Michigan.

|

Away from the city, the lakefront was increasingly dotted with large industrial developments in the latter part of the century. By 1900 the lake's shore was divided into discrete zones of recreational, residential, agricultural, and industrial uses.

|

In 1909, Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett published their comprehensive plan for Chicago. The Burnham Plan, adopted by the city, prescribed the expansive recreational development of the lakefront and the Chicago River. Included was a plan for the construction of a pier in the lake, eventually known as Navy Pier.

|

Subsequent changes to Chicago's waterfront have increased its recreational uses. When, in 1973, Mayor Richard J. Daley mused that he would like to see the day when people fished and grilled their catch on the river's shore, the idea seemed far-fetched. However, this scenario has become possible with increased environmental awareness, sewage treatment, and the work of special interest groups such as the Friends of the Chicago River. In a symbolic gesture reflective of this activity, the city in 1989 dedicated the Chicago Water Arc, which shoots water over the Chicago River from McClurg Court.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.