| Entries |

| S |

|

Schooling for Work

|

|

The need for schools to adjust to the new industrial age was not at issue. Few people thought that the schools should merely replicate the traditional curriculum. As John Dewey pointed out in a series of lectures at the University of Chicago at the end of the nineteenth century, the rapid changes that industrialization brought with it required a radically different education. The new industrial society had disrupted the natural transition from childhood into the world of work. Children no longer learned about work through informally observing their parents, and, in Dewey's words, the school had become the legatee institution and needed to take on an expanded role, providing an education that went well beyond the traditional three R's. For Dewey, this would not include preparing children for any specific occupation but rather for the ability to respond to new needs and new tasks. The study of occupations would be a central part of the curriculum in Dewey's laboratory school—important not as vocational training but as a way of helping children to understand the new industrial world around them.

At the same time, members of Chicago's powerful business community also recognized that schools could play a crucial role in preparing the next generation of workers. They argued that schools should offer a vocational curriculum to future factory and office workers while, at the same time, inculcating the habits necessary for work. The schools also needed to undertake the essential task of Americanizing the large number of immigrants who were increasingly providing the city's labor needs. For schools to socialize the children of immigrants and the poor, they needed to develop a curriculum that would keep them in school longer. A “practical” course of study which offered a path to employment was the answer.

At first, Chicago's businessmen agreed with educational reformers like Dewey and welcomed the idea of manual training in the schools. Giving children a basic knowledge of how to use tools was important. But by the early years of the twentieth century, as the demand for more highly trained labor became ever more imperative, they began to argue that the schools should go beyond manual training and teach actual trades. Impressed by the growing commercial competition from European nations and especially Germany, the Chicago Commercial Club (Chicago's most prestigious business club) commissioned former superintendent of schools Edwin Cooley to visit Europe to study their systems of vocational education. In the wake of his report of 1911, businessmen increasingly supported a differentiated system of vocational education, with the high schools preparing the “noncommissioned officers” of an industrial army and vocational schools furnishing the well-trained soldiers that modern industry required. The new vocational education, as differentiated from manual training, would “consist of the actual trade processes” and produce “articles of commercial value” under “conditions of the occupation outside the school.” Such vocational programs would be gender-specific, preparing children for careers in a highly differentiated job market.

In 1912 the Chicago Public Schools adopted the new philosophy and introduced a differentiated curriculum, encouraging sixth graders to choose between an academic and an industrial track. The latter would lead to a two-year high-school vocational program. The Board of Education also established different kinds of high schools—technical schools with both two-year and four-year programs that prepared students for skilled laboring positions or technical colleges. In these schools even the “academic” subjects took on a workplace orientation. Instead of history, for example, they offered “industrial history.” Overtly vocational education also infiltrated the general high schools, and by 1913, 16 of the city's 21 high schools had become composite high schools offering vocational courses in addition to academic work. The board also offered “continuation” courses in which children already in the workforce could improve their work skills and enhance their ability to find more highly skilled jobs. At the same time, again at the behest of businessmen, the board instituted a program of commercial courses—such as bookkeeping, typing, and business English—in the high schools. The commercial program eventually included more specialized courses in selling and advertising. By 1914, one-third of Chicago's high-school students were enrolled in day and evening commercial courses.

Although the radical shift in the program of the schools did not arouse immediate opposition, it led to a great debate and a political crisis in 1913. Supported by members of Chicago's business elites, former superintendent Edwin Cooley recommended that Illinois establish a state system of vocational education. Cooley's proposal would have established full-time vocational schools and, for youngsters already in the workforce, continuation schools, in a school system that would be fully separated from the regular public schools. The new program would be governed by independent boards, made up of men with practical experience in industry and commerce, and funded by a special tax. Promoters of the Cooley plan had an additional agenda; a major goal of the new venture would be to shape the ideology of the working class as a way of fighting radicalism, promoting the morality of hard work, and instilling such industrial virtues as punctuality.

The Cooley bill, introduced several times between 1913 and 1917, was strenuously opposed by Superintendent Ella Flagg Young (a disciple of Dewey), the Chicago Teachers Federation, and the Chicago Federation of Labor. First and foremost, opponents protested that the Cooley plan was undemocratic; it would lead to permanent class divisions by stifling social mobility. Opponents shared the opinion of the Illinois State Federation of Labor, which charged that the specialization it would encourage would prevent children from “acquiring the skills and training necessary to the continued development, or even proper maintenance of various trades and callings.” Moreover, labor leaders saw the plan as an ill-disguised attempt to turn the public schools into institutions that would supply industry with a well-trained and docile (non-union) workforce. It would weaken trade unions by taking away their role in admitting new workers to apprenticeship programs. Unionists saw the new vocational schools as little more than potential “scab factories.” Professional educators bristled at Cooley's assumption that vocational education, to be efficient, had to be “kept out of the hands of the old fashioned school master.”

The critics were correct in pointing out that the new vocational education plan constituted a radical reorientation of public education. Horace Mann and the common school reformers of the pre–Civil War period had seen education as the great equalizing institution, bringing rich and poor, immigrants and native-born, together in the same classroom, where they would be offered equal opportunities for advancement. Dewey, too, saw the classroom as the basic unit for building a democratic community. For him, manual training was a gateway to understanding the modern industrial world, not preparation for a specific trade. Contrary to the educational reformers' vision, advocates of the new vocationalism would divide children at an early age; those who were thought destined for factory or clerical work would go to different schools from those who would be offered academic courses. The children of the poor and immigrants would be relegated to the dead-end vocational track.

Businessmen countered the argument that the new program was undemocratic by contending that offering children the chance to learn a trade fostered economic mobility and reduced potential class conflict. Indeed, preparing children for a specific trade was now a requirement for citizenship education. They also argued that in a separate school system men with practical experience (as opposed to educational credentials) could be hired to teach.

Although the business-minded reformers lost the battle over the Cooley bill, they were able to attain many of their objectives with the federal Smith-Hughes Act (1917). This provided funds for vocational education and, like the ill-fated Cooley bill, allowed states to establish separate vocational education boards. Under the auspices of Smith-Hughes, businessmen attained their primary goal—a program of training students for specific skills, directed by people of practical experience.

The divisions revealed by the Cooley bill resurfaced in 1923, when a new, efficiency-minded superintendent, William McAndrew, proposed a system of junior high schools. When teacher representatives asked him if the junior high schools would offer terminal programs for children not headed for high school, McAndrew was evasive, and it became clear that these new schools could easily become vehicles for tracking children of the laboring classes into vocational programs while the children of the higher classes were being prepared for high school (this, in effect, was what they believed had happened in the schools of Rochester, New York). McAndrew, who believed that teachers should follow orders rather than give advice, went ahead with his plans and tried to avoid further consultations with them. Instead, it became clear that he was eager to consult the businessmen who had supported the Cooley plan. The board adopted the new program, despite the opposition of many of those who had united to oppose the Cooley plan. Although the worst fears of the opponents were not realized by the junior high schools, the controversy was significant because it revealed once more the way in which the issue of schooling for work could uncover the tensions between business and labor in Chicago.

The Great Depression had a devastating impact on all aspects of Chicago's public schools, including its vocational programs. No major city in the United States was in worse financial condition when the crisis began. The impact of the national crisis was exacerbated by the high degree of corruption and racketeering that had infected the administration of Chicago's schools as well as persistent revenue battles between Chicago politicians and representatives of downstate Illinois. In 1933, faced with a devastating financial crisis, the Board of Education increased teachers' workloads, slashed their pay, and cut many programs, including most vocational courses. In 1936, however, while the schools were still suffering under the draconian cuts imposed by a highly politicized school board, a new attempt to promote vocational education revived the bitter battles that had been fought over the Cooley bill. William H. Johnson, who became superintendent after the death of the popular William J. Bogan, was a man who was distinguished largely for his personal ambition and his subservience to an economy-minded board. Faced with the continuing financial crisis, he saw that a new emphasis on vocationalism could be a money-saving proposition. First he cut back the number of “major” academic subjects that high-school students could take. He then boldly proposed allowing only 20 percent of Chicago public school students to enter academic programs and sending the others into vocational courses. Since the salaries of vocational teachers were heavily subsidized by the state and federal governments under the Smith-Hughes Act, replacing teachers of academic subjects with vocational teachers would relieve some of the financial pressure on the Board of Education.

Johnson's proposal was even more restrictive than the Cooley plan. It not only threatened the democratic ideal of equal access to academic opportunities, it also directly attacked teacher tenure. Like his predecessors Cooley and McAndrew, Johnson was a moralist who sought to use vocational programs as a way of shaping the working classes. After a great storm of popular protest, which included charges that the plan to use the educational system to sort students into occupational niches was a “fascist” device, Johnson claimed that his original proposal had been “misunderstood” and he withdrew the plan. The proposal indicated once more, however, that there were still those who saw public education as a way of sorting children into appropriate vocational categories, and, despite the failure of the Cooley and Johnson plans, this was, in fact, how vocational education often functioned in Chicago.

The increased use of vocational education as a sorting device was facilitated by the fact that during the Depression, the Chicago labor movement, which had been a leading force in opposing the creation of a dual track educational system, had abandoned its concern for such broad educational issues. Organized labor was in large measure co-opted by Chicago's powerful Democratic political machine. The Chicago Federation of Labor now concentrated on getting its share of political rewards by emphasizing such bread-and-butter issues as the salaries of school custodians and maintaining labor representation on the school board. It no longer supported the teachers' demand for increased school funds nor their campaign for a more democratic system of education.

The use of vocational education to sort children became central to a program for “prevocational” education in the upper elementary grades with the establishment of vocational centers for children who were 14 or older and still enrolled in the sixth grade. Beginning in 1913, these children were offered special vocational classes—one set for boys and a different set of courses deemed appropriate for girls. While the intent of the program was expressed in the language of John Dewey as appealing to the interests and needs of the child, in their actual operation, pre-high-school vocational schools became disproportionately the schools for children seen as lacking the intellectual abilities for the regular academic program. In addition, children who were troublesome for the schools—chronic truants and children who misbehaved—were increasingly shunted into these programs. As a result, of course, the reputation of the vocational programs suffered. Good students were discouraged by their parents from attending these schools, and they became virtually reform schools. By 1941 (a typical year), the average IQ of children attending the Chicago Public Schools' vocational centers was 79.

After World War II, it became clear that Chicago's vocational program (as in so many other cities) was highly segregated by race. The best programs with the best connections to the job market were in white neighborhoods. As late as the 1960s, Washburne Trade School, which accepted only students who had been granted apprenticeships by the notoriously racist unions of the building trades, had an enrollment that was 99 percent white. When, in the 1980s, pressured by a federal consent decree, Washburne finally opened its doors to minorities, a number of the skilled unions drastically cut their programs or withdrew completely from Washburne. African American youth were served by Dunbar Vocational Center (which was not promoted to high-school level until 1952) and other vocational schools that had inferior equipment and instruction. Dunbar's curriculum followed the highly segregated Chicago labor market by offering only programs leading to the less-desirable, lower-paid trades.

Deindustrialization dealt an even more serious blow to meaningful schooling for work in Chicago's African American neighborhoods. As the steel mills and meatpacking industry left the South Side, new industries did not replace them, and by the 1970s it was clear that there were few jobs for which even the most successful vocational programs could provide an entry. As unemployment in the vast ghettoes of Chicago climbed, schooling for work became ever less relevant to the young people growing up in a community that was increasingly isolated from the rest of the metropolitan area.

Reformers who valued social efficiency eventually won the battles over vocational education in the Chicago Public Schools that had begun early in the twentieth century. While the best of the vocational programs succeeded in preparing workers for the industrial and commercial needs of the city, for many children, especially the poor, vocational education provided a relatively inexpensive way to meet the requirements of compulsory attendance laws.

After World War II, as the world became more and more reliant on technology, much of the focus on schooling for work shifted to community and junior colleges and their vocational centers, administered by the City Colleges of Chicago. Malcolm X College, founded in 1911 as Crane Junior College and located on the West Side near Cook County and St. Luke's Presbyterian Hospitals, offered a large number of vocational programs in the health sciences, in addition to courses in computer science and the child care professions. Truman College, located in the Uptown neighborhood, advertised itself as the most “richly diverse” of any community college in Illinois. Building on an institution begun in 1956, Truman has served Native Americans and immigrants from Latin America, Asia, and Poland. It offered, among other vocational programs, nursing, pre-engineering, chemical -industry technology, and child development. The City Colleges also established a number of job skills centers. The one established by Olive-Harvey College, located in the African American community in the Southeast Side's Pullman neighborhood, trained workers for entry-level jobs such as counter person, bank teller, nurse's assistant, and security guard.

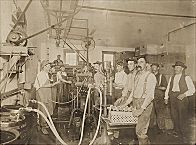

The public school system was by no means the only source for vocational education in Chicago. From the earliest days, Americans have gone to school to prepare for specific careers by attending private, entrepreneurial schools, and in the dynamic economy of early-twentieth-century Chicago, these schools proliferated. By 1898 a Chicago directory listed schools as varied as the Chicago School of Assaying, the Chicago Nautical School, and at least four shorthand schools. Schools listed in later directories include several millinery schools, the Chicago School of Bookkeeping, as well as the Wahl-Henius Institute of Fermentology and the Zymotechnic Institute and Brewing School. While these schools differed in quality, their persistence indicates a continuing demand by Chicagoans for schooling directed toward preparation for specific careers.

Perhaps the best known of Chicago's entrepreneurial schools was founded in 1931 by Herman A. DeVry, a pioneer in developing motion picture projectors. With a loan from a friend, DeVry purchased a defunct school with 25 students and three employees. Its purpose was to train students for technical work in electronics, motion pictures, radio, and, eventually, television. The DeVry Institute has trained thousands of people and now awards college degrees as well as certificates. Purchased by Bell and Howell in 1967, the school rapidly expanded beyond its Chicago base and established campuses in several other states as well as Canada.

Schooling for work in Chicago also involved a great number of postgraduate institutions. Foremost among these were programs in teacher education, initially offered as part of the public school program. The metropolitan area also offered graduate training in law, medicine and nursing, and business. Except for teacher and nursing education, these programs were quite different from most schooling for work in that they attracted mostly middle-class participants. And unlike precollegiate vocational education, they provided genuine opportunities for social mobility.

The story of schooling for work in Chicago is, of course, one aspect of a national problem. Vocational education has never been simply a way of preparing youngsters for work; it has also been called upon to serve children who are unmotivated or lack academic abilities in a system that requires them to be in school. The great pressures to deal with the second problem have meant that the first motive often has gotten lost. Another limit on schooling for work within the public school system has been finding the flexibility to deal with a rapidly changing job market. The Smith-Hughes Act compounded this by its emphasis on agricultural work and other trades that rapidly became irrelevant to the needs of employers. Absent the requirement of serving as a means of keeping unmotivated and frequently troublesome children in school, however, the Chicago City Colleges and the private, entrepreneurial schools were able to concentrate on preparing people for new jobs—and this they have done with notable success.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.