| Year Pages |

| 1968 |

|

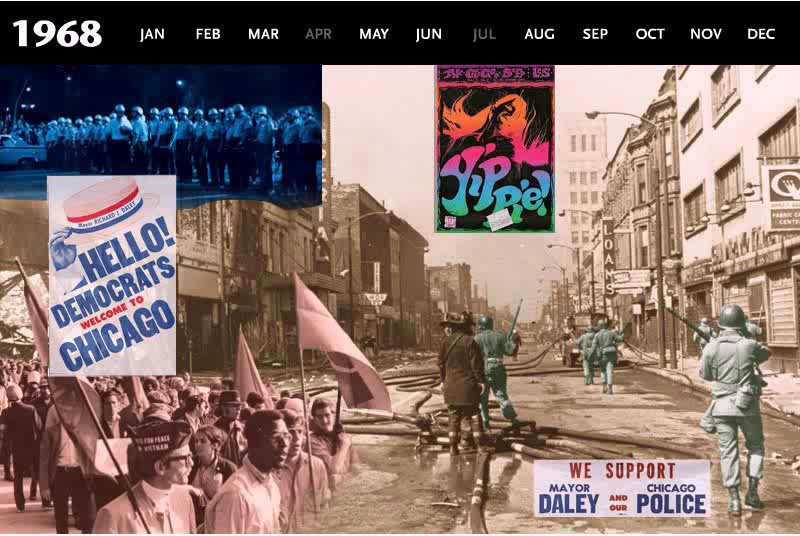

As 1967 ended, Chicagoans anticipated a good year. The local economy was booming, supported by government defense contracts and Great Society social welfare expenditures. With over three and a half million people, Chicago was the nation’s second-largest city, full of well-paying jobs for hard-working people. But 1968 quickly turned sour. National antiwar organizations announced they would protest in Chicago during the August Democratic National Convention. Chicago-based comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory threatened convention-week protests if the city did not get an open housing bill and promote African American policemen to high-ranking posts. On April 4, disaster struck when Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. Three days before, the Chicago Tribune had editorialized against his support for striking Memphis sanitation workers, calling him “the most notorious liar in the country.” In a memorial service at City Hall, Rev. Jesse Jackson indicted the political establishment, exclaiming, “The blood is on the chest and hands of those that would not have welcomed King here yesterday.” Despite pleas from the city’s African American leadership, rioters filled the streets of Lawndale, looting and burning. Parts of the South Side also burned. During the conflagration, Chicago police, following the orders of superintendent of police James B. Conlisk, tried to use minimal force and avoid unnecessary bloodshed. Once order was restored, however, mayor Richard J. Daley attacked Conlisk’s approach: “I said to him very emphatically and very definitely that an order be issued by him immediately and under his signature to shoot to kill any arsonist . . . and to issue a police order to shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting any stores in our city.” Later, the mayor backed away from his extreme position. Nonetheless, four months later when the convention came, authorities wanted no disorder. Far from the cordoned-off International Amphitheater where Hubert Humphrey won the presidential nomination, protesters and police met in angry confrontations. The worst occurred August 28 after police stopped protesters from marching to the convention center. A crowd of some 10,000 ended up near Michigan Avenue and Balbo Drive. As protesters chanted “The whole world is watching” and television crews filmed, policemen beat hundreds of protesters bloody. Some 83 million Americans watching their televisions to see democratic process at work instead saw a street riot. The violence poisoned Humphrey’s bid locally and nationally. Unlike in 1960, Chicago’s Democratic machine could not turn out enough votes. Illinois, like the nation, went Republican. By the end of 1968, Chicago had become a tragic symbol for a nation that had come undone.

|

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.