| Year Pages |

| 1919 |

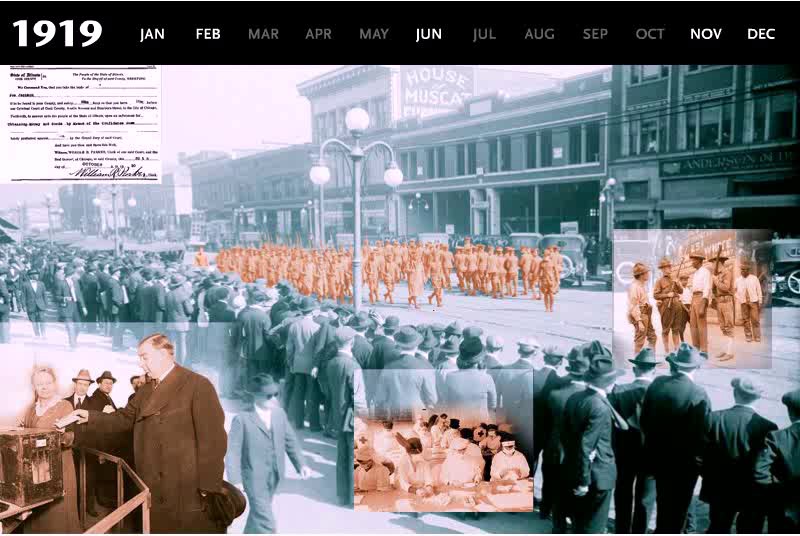

|

Although most Chicagoans enthusiastically greeted the end of World War I in November 1918 and the subsequent return of local soldiers, they knew that the future held many unanswered questions. The influenza epidemic that attacked the city--and the world--had not been contained. Many had already perished; by the time the epidemic was declared finished, more than 20,000 Chicagoans would die. By mid-1919, production had already begun to decline, and employment along with it. Returning soldiers worried about whether they could reclaim their jobs. African Americans who had arrived during the war as part of the Great Migration feared that white soldiers would indeed claim jobs--and at their expense. And between 1919 and 1921 a brief spurt of immigration from Europe would add more newcomers to the mix. Race and employment were the tinderboxes in Chicago in 1919. On July 27 a stone-throwing incident between white and black residents at the 29th Street beach led to the drowning of Eugene Williams, a young African American swimmer. His death erupted into a riot that ultimately claimed the lives of 23 blacks and 15 whites and left 537 wounded or maimed. In September, steelworkers around the country declared a strike that closed factories in Chicago and its suburbs and led to violent confrontations and large-scale arrests in Gary. Local violence combined with national and international events to make Chicago a major target of attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer’s attack on radicals. So wide was his net that the Industrial Workers of the World, headquartered in Chicago, and corporate leaders of firms like International Harvester and the packinghouses were all under suspicion, the first for advocating socialist and anarchist solutions, the second for trying to maintain their long established commercial ties with Russia after the revolution. If notions of Americanism were open to question, so, too, were civic pride and integrity. Throughout the summer, Chicagoans had celebrated their White Sox, seemingly the best team in professional baseball. But the Sox lost the World Series, and by the end of the year, Chicagoans--baseball fans and otherwise--knew about the bribes and the gamblers. Still another question loomed large for the future. On October 28, 1919, Congress passed the Volstead Act, providing for the enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution that prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of alcoholic beverages in the United States.

|

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.