| Entries |

| C |

|

Clubs, Fraternal

|

|

At fraternalism's peak of popularity in the late nineteenth century, most middle-class and many working-class men belonged at least briefly to a lodge. Millions of lodge brothers paraded in colorful fraternal dress, honored their officers with extravagant and even ridiculous titles, and found a sense of community at the lodge hall. Many fraternal societies provided their members with life insurance and sometimes with sickness insurance. The best-known fraternal societies accepted only white men and often only Protestants as members, although many had auxiliaries for women. There also were auxiliaries for youth, sometimes with quasi-military drill teams. Other fraternal societies sprang up for the excluded to meet their need for sociability and a sense of personal and collective importance. Immigrants and blacks, Roman Catholics and Jews had their own societies. German, Scandinavian, and East European lodges for many years operated in their own languages. There were other specialized orders, notably the temperance fraternal societies that provided mutual support in the battle for individual sobriety and prohibition.

|

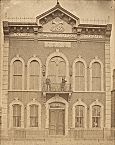

The best-known fraternal organizations in the United States have been the Masons, the Odd Fellows, and, most recently, the Elks. Chicago's first Masonic lodge was chartered in 1843. Numerous and mostly middle class, the Masons constructed the Chicago Masons Temple in 1892, which at 22 stories was then the world's tallest building. The Odd Fellows chartered their first Chicago lodge in 1844. By 1923 this order counted 89 Chicago lodges with nearly 28,000 members. Adapting to a changing population, the Odd Fellows chartered a Spanish-speaking lodge in 1971. The first Elks lodge in Chicago was chartered in 1876 and was especially popular among actors. Unlike most fraternal societies that declined in membership in the early 1900s, the Elks added members until well after World War II. The Elks reached their greatest Chicago membership, 4,300 in four lodges, in 1958. By the end of the twentieth century their Chicago-area lodges were all located in the suburbs, outside the city limits.

Many of the black fraternal organizations active in Chicago were the segregated and unacknowledged counterparts of white societies such as the Masons, the Odd Fellows, and the Elks, but newcomers from the southern states brought with them new societies such as the True Reformers. Lodge membership played an important role in community politics. By the eve of World War II, the Chicago membership of black fraternal orders had fallen to about 10,000, mostly middle class and few of them active in their organizations.

Even in their heyday fraternal societies had enemies. Evangelical ministers and women dominated the anti-secret-society National Christian Association, organized in Illinois in the late 1860s. Its leader was the founder and first president of Wheaton College, which as a result became an anti-secret-society stronghold. To expose the fraternal societies, the National Christian Association's publisher, Ezra A. Cook of Chicago, printed many secret society rituals. The Roman Catholic Church also condemned membership in secret societies, so Catholic fraternal societies such as the Knights of Columbus emphasized that their ritual was not secret.

In the twenty-first century, ritual and regalia have lost their appeal. To most people, they appear absurd. The lodge members who remain are often elderly. Other than the Masons, the Odd Fellows, and the Elks, few fraternal societies survive except as mutual insurance organizations whose members seldom meet.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.