| Entries |

| B |

|

Broadcasting

|

|

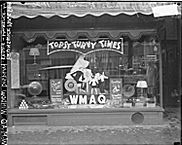

Chicago's age of broadcasting began the evening of November 11, 1921, when KYW (licensed to Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company and operated jointly with Commonwealth Edison) began regular scheduled programming. For the next two months, KYW aired live performances of the Chicago Grand Opera Company—and nothing else. Managers of a later era might cringe at the thought of an “opera-only” station. But in 1921, only a year after Westinghouse's pioneer KDKA went on the air in Pittsburgh, the content of programs was secondary to the novelty of the medium. Westinghouse claimed there were 200 radio receivers in Chicago when the 1921 opera season began, 25,000 when it ended. KYW's live opera broadcasts were a major factor in the spread of America's “radio craze” and the creation of a local radio boom.

|

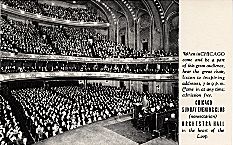

The extension of AT&T's network lines to the West Coast in November 1928 turned Chicago into a national radio production center. Both NBC and CBS were committed to an 18-hour broadcast day. The time couldn't be filled without Chicago's participation.

|

Chicago rapidly lost its status as a network radio production center following the end of World War II. But the completion of the coaxial cable linking the East Coast and Midwest in January 1949 turned it into the origination point of some of early television's most memorable programs. WBKB (licensed in 1939 to the Balaban and Katz theater chain) had already trained the medium's first generation of technicians and producers. Network radio's departure had left a substantial pool of underutilized talent. Critics called the programming that resulted the “Chicago School of Television.” Technically innovative on the one hand, simple and straightforward on the other, the “Chicago School” was above all characterized by the belief of its proponents that television was a unique medium unto itself.

By the mid-1950s, most of Chicago's major network television talents had been lured to the East or West Coasts. Emerging videotape technology meant that Chicago's studios were no longer necessary for live network broadcasts. At WGN-TV in particular, children remained a key target of local programming. A generation of Chicago's youth grew up watching Garfield Goose and Friend, while at least two generations watched (and hoped they could acquire tickets for) Bozo's Circus. But increasingly Chicago's commercial stations directed their resources toward local news coverage. The quality of local television news in Chicago generally remained high, thanks to the city's strong newspaper tradition and seasoned radio journalists like Clifton Utley and Len O'Connor who brought their skills to the video medium. Meanwhile, WTTW (licensed in 1955) evolved into the nation's most-watched public television station.

|

In the 1970s music, for the most part, moved to the FM band. Three decades after Zenith Radio's Eugene McDonald put experimental station W51C on the air, FM had become profitable. Popular music dominated the dial. But Chicago's audience still supported two fine-arts stations, WFMT and WNIB. Paul Harvey remained Chicago's lone network radio personality. His daily news and commentary broadcasts were almost as long-lived as the ABC network that carried them.

But long after satellite dishes supplanted the network lines that once made Chicago a broadcasting hub, tens of millions of Americans continued to watch Chicago-made programs, thanks to the growing popularity of syndicated daytime television talk shows. Phil Donahue pioneered the genre. Oprah Winfrey perfected it. Jenny Jones and Jerry Springer threw it (sometimes literally) into the arena of controversy. And Chicago remained a national broadcast production center.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.