| Entries |

| T |

|

Theater Buildings

|

|

Time and again in the mid-nineteenth century, theaters were built, burned down, quickly built again (with promises of being fireproof ), and burned again. From the first Chicago theater, built by John Blake Rice in 1847 and rebuilt following a fire three years later, through the Great Fire of 1871 and until the end of the century, fire kept Chicago's theaters in a state of constant regeneration not unlike the surrounding Illinois prairie. The final straw came during a holiday matinee on December 30, 1903, when the burning of the Iroquois Theater killed 602 patrons. This fire inspired nationwide ordinances ensuring that all public exit doors must open outward. Locally, it led to fire codes that were so restrictive they severely limited theatrical growth in the city for three-quarters of a century. Small groups in particular found it difficult to fashion performing spaces out of storefronts and warehouses without running afoul of regulations involving fire curtains and multiple exits. When those building codes were finally relaxed, the half-dozen small theaters that sprang to life led the off-Loop theater movement to develop an intimate style of performance that gained considerable renown. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the cramped nature of these venues, the acting was often astonishingly powerful.

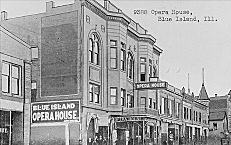

Chicago's more imposing theater buildings include Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan's ornate Auditorium Theater, the Goodman Memorial Theatre, Crosby's Opera House, McVicker's Theatre, and Steele MacKaye's grandly designed but never built Spectatorium. Late in the twentieth century, the Oriental and Chicago theaters, both built as movie houses in the 1920s, were refurbished to house theatrical productions. Two neighboring theaters, the Harris and the Selwyn, both built in 1922, were extensively renovated and used by the Goodman Theatre Company, beginning with the 2000–2001 season. All of these were built in the Loop. Other notable theaters built in the past quarter century include the Apollo (1978) and the Royal George (1986), both on Lincoln Avenue, the Steppenwolf (1991) on Halsted, and, on Navy Pier, the Chicago Shakespeare Theater (1999), which is unusual in its towering seating area, which, although indoors, was inspired by the Globe. Of course, no one knows for certain what the Globe looked like, since it, too, burned to the ground. With the threat of fire and restrictive fire codes largely a thing of the past, Chicago has become a city of smaller venues scattered far and wide and larger buildings and renovations clustered in and around the Loop.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.