| Entries |

| B |

|

Baths, Public

|

|

A women's reform organization in Chicago, the Municipal Order League (later renamed the Free Bath and Sanitary League), led the campaign for public baths. Three women physicians, Gertrude Gail Wellington, Sarah Hackett Stevenson, and Julia R. Lowe, headed the crusade. Beginning in 1892, Wellington led in the effort, utilizing the network of women reformers in Chicago centering in the settlement houses, especially Jane Addams's Hull House, as well as the Chicago Woman's Club and the Fortnightly Club. These women gained support for the cause of public baths from the press and the city government under Mayor Hempstead Washburne and city council finance committee chairman Martin Madden. Chicago's first public, bath located at 192 Mather Street, near Hull House on the Near West Side, opened in 1894. It was named after assassinated mayor Carter H. Harrison and cost $20,649. Thereafter, Chicago public baths were generally named after prominent local citizens.

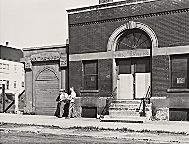

Although some American cities built elaborate, monumental, and expensive public baths, Chicago conformed to the bath reformers' ideal that public bathhouses should be modest, unpretentious, strictly functional, free, and located in poor and immigrant neighborhoods readily accessible to bathers. Chicago's bathhouses generally contained between 20 and 40 showers, with attached dressing rooms, and a waiting room. There were no separate sections for men and women; two days a week were reserved for women, girls, and small children with their mothers. Bath patrons did not control water or temperature, which were regulated by an attendant who turned on the shower for 7 to 8 of the 20 minutes allowed for a bath.

In spite of this functional emphasis, bath patrons utilized the public baths more to cool off in the summer than to bathe in the winter months. Additionally, utilization of the public baths began to decline even as the city opened new baths. Peak attendance was reached in 1910, when a total of 1,070,565 baths were taken in the 15 bathhouses in operation; by 1918, when 21 bathhouses were open, utilization had declined to 709,452 baths. The opening of bathing beaches and swimming pools in the early 1900s, as well as housing reform laws which required private toilets in apartments (many landlords added bathtubs as well), contributed to the decline in public bath usage.

After World War II, Chicago began to close down its public bathhouses. By the 1970s only one bathhouse remained open, to serve Skid Row residents, and that too closed in 1979.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.