| Entries |

| O |

|

Outdoor Concerts

|

|

As early as 1851, citizens enjoyed outdoor concerts when the Great Western Band performed in Dearborn Park. After the Civil War, regimental bands filled the summertime air in squares, parks, private picnic grounds, and commercial summer gardens. Immigrant and ethnic groups, most notably Germans, Bohemians, and Poles, organized concerts to celebrate musical traditions, mobilize attention to issues, and express the vitality of their communities.

|

As Chicago urbanized, concert audiences diversified and groups sometimes sparred over appropriate behavior. Park commissioners expected middle-class respectability to prevail but did their best to accommodate differences of musical taste among patrons. In the 1900s and 1910s, municipal outdoor concerts expanded as part of an effort to reform recreation among the residents of Chicago's industrial neighborhoods.

World War I inspired many ethnic groups to organize outdoor concert rallies in parks and at Soldier Field to express love of their homelands and their loyalty to the United States. In 1914 the Civic Music Association promoted “music for the people” in the form of outdoor classical concerts. The association also sponsored “ Americanization ” public sings in parks and at Navy Pier involving thousands of children and their parents. Commercial amusement parks like White City and Sans Souci featured regular outdoor concerts too.

Despite the persistence of ethnic community concerts, concerts increasingly catered to the population of Chicago-at-large. In the late 1920s, the Chicago Tribune inaugurated a “ Chicagoland Music Festival” by invoking a public identification with its imagined community of readers. By the late 1940s, the festival attracted tens of thousands of spectators and radio listeners. To bolster civic morale and aid unemployed musicians during the Great Depression, James C. Petrillo, President of the Chicago Federation of Musicians, helped initiate outdoor concerts in Grant Park, including an annual symphonic series begun in 1935. The WPA Federal Music Project helped sustain outdoor concerts by the Illinois Symphony Orchestra and the Chicago Women's Symphony Orchestra. The Grant Park Symphony and the Petrillo Bandshell were legacies of this public vision.

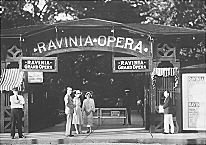

Racial segregation complicated the history of the outdoor concert as a democratic phenomenon. African Americans often avoided public concerts outside their own neighborhoods. But after the Depression, opportunities for blacks gradually increased. In the 1940s, the American Negro Music Festival annually brought classical and popular musical artists such as Roland Hayes, Louise Burge, Thomas A. Dorsey, and Dorothy Donegan to Soldier Field and Comiskey Park. By the 1970s and 1980s, popular tastes in commercial music helped sustain Chicagofest, which brought national pop, blues, and jazz performers to Navy Pier. The Chicago Jazz, Blues, and Gospel Festivals followed, along with classical and popular concerts in Grant Park and other public city parks. At the opening of the twenty-first century, residents and visitors could enjoy a host of summertime concerts, featuring Celtic and Latin music, reggae, country, and opera.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.