| Entries |

| L |

|

Landscape

|

|

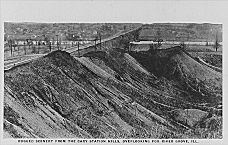

The great ice sheets of the glacial age then pushed southward from Canada and rearranged the landscape, leveling the hills, filling in the valleys, excavating Lake Michigan's basin, and leaving debris of soil and rocks in a series of moraines that marked pauses in the retreat of the ice sheets. These recessional moraines ringing today's Lake Michigan dammed up the melt waters and created a series of great glacial impoundments that eventually became the Great Lakes. Before reaching their current configurations, however, the glacial lakes underwent a series of dramatic fluctuations. Lake Chicago emerged at one high point, covering an area larger and deeper than today's Lake Michigan. Eventually, melting water poured over the moraines, creating a spillway that drained Lake Chicago down to the current lake level.

|

The old lakebed itself was crossed by a series of former beaches and spits which offered better drainage because of their sandy soil. These sites were often marked by different vegetation as the glaciers retreated and a warm-summer, continental climate returned to the area. These ridges and beaches then became animal traces and Native American trails, later turning into pioneer roads. Some survive as modern thoroughfares.

When the ice sheets left the Chicago area for the last time about 13,000 years ago, a tempestuous weather pattern set in which further softened the landscape. Depressions were filled in with wind-driven soil while the melt waters flowing southward sorted out sands and gravel deposits which became resources for the later building of the city. Huge chunks of ice were left behind as the ice retreated.

Sometimes buried in the process, then slowly melting, they created depressions which became ponds and lakes. These pockets, and others created by the retreat of the ice and the rush of the melting waters, gradually filled with vegetation, turning into wetlands, sloughs, and peat bogs and covering much of the landscape, even on the higher elevations of the moraine.

The vegetation that reclothed the region in the postglacial period included wetlands and dry lands. The dry lands divided again into woodlands and grasslands, which nineteenth-century Americans respectively labeled groves and prairies. Grasslands came first and supported an array of large mammals: mastodons, mammoths, bison, elk, and their predators, like saber-toothed tigers and human beings. It was the latter, the early big-game hunters, who probably saw an advantage in encouraging the natural prairie fires which, started by lightning, kept the grasslands largely free of shrubs and trees. These fires maintained a prairie landscape in a climatic region that should have reverted to a forested region in due time. Indeed, the great forest extended from the north and the east up to the fringes of the Chicago area in historic times, but a prairie peninsula reached eastward to touch the Great Lakes at the site of Fort Dearborn. Groves of oak and hickory dotted the prairie sea like islands when Americans first arrived, offering prime sites for pioneer settlement.

These nineteenth-century Americans settlers took on the massive task of changing the vegetation and altering the landscape to support their way of life. They looked upon the lands and the rivers as tools and resources. Trees were cut for lumber and fuel, the grasslands turned into pastures and fields, and Old World plants and animals replaced the native flora and fauna. Wetlands were drained and lowlands filled to make better use of the land. In the city of Chicago, the surface was raised to improve drainage, the shore line was filled in to gain land, the river was channelized and straightened, and its flow was reversed by deepening the canal in the spillway and placing a low dam at its mouth. New lagoons, ponds, and harbors were dug to help control storm waters or to create park lands and recreational areas.

The motto of the early city was “City in a Garden,” and lots were made deep enough so that sidewalks and houses could be set back from the streets, creating “parkways” and “front yards” to display lawns and flower beds developed from imported plants. The use of the government land survey to create a grid of streets, rectangular blocks, and lots created a formal geometric urban plan, much more textured than but fully compatible with the pattern of farms and fields surrounding the city. The park movement in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the subsequent creation of a greenbelt of forest preserves, and the open lands movement in the twentieth century have created, preserved, or recreated various types of alternative landscapes.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.