| Entries |

| A |

|

Art, Public

|

|

Much public art was produced in the period between the fair and World War I: statues of such famous men as Shakespeare, Franklin, Garibaldi, Leif Ericson, Hans Christian Andersen, and Kosciuszko appeared in a 10-year period, as well as monuments to the Confederate dead and the Fort Dearborn Massacre and several major fountains. The Ferguson Fund, created in 1905 to “memorialize events in American history,” bore first fruit with Lorado Taft's Fountain of the Great Lakes. Nearly a score of other notable works ensued, such as Taft's Fountain of Time (1922) at the Midway. Whether such abstract works as Henry Moore's Sundial (1980), at the Adler Planetarium, and Richard Hunt's Slabs of the Sunburnt West (1975), on the University of Illinois at Chicago's campus, fit the spirit of the bequest has inspired considerable disagreement.

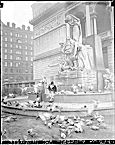

In the 1920s, such works as Ivan Mestrovic's Indians (1928) and Parisian Marcel Loyau's sculptures for the Buckingham Fountain, the world's largest at the time (1927), captured the city's imagination. The Great Depression and war years limited opportunities for large public works of sculpture, yet Ceres (1930), atop the Board of Trade Building, by the expatriate Chicagoan John Storrs, is a striking art deco departure from naturalist modeling.

The Federal Art Project in Illinois was responsible for hundreds of fresco and oil murals in schools, hospitals, and post offices, in Chicago and the suburbs. Lane Technical High School alone was graced with abstract figurative work by John Walley, historic narratives by Edgar Britton, and scenes of contemporary life by Mitchell Siporin. Ethel Spears, Mildred Waltrip, and others painted in both Chicago and Oak Park but lived to see their work destroyed or removed in response to changing taste and values. The revival of mural painting in the 1960s had a more positive effect on the extant work of the 1930s, stimulating an interest in preservation and restoration that continued into the 1990s. In other media, eastern artist Henry Varnum Poor produced ceramic tile murals of Carl Sandburg and Louis Sullivan for the Uptown Post Office (1943).

The 1960s were a golden age for public art, with both increased attention to sculpture and a new generation of muralists coming of age. Well-known European sculptors received major commissions: Antoine Pevsner, Henry Moore, and Ruth Duckworth for the University of Chicago, and Pablo Picasso, for his sculpture (1967) at the Daley Plaza. The Picasso, Marc Chagall's mosaic The Four Seasons (1974), and Claes Oldenburg's Bat Column (1977) were all originally derided but have become as popular as some of the historical pieces. The pivotal piece in the revival of murals for the public was William Walker's Wall of Respect (1967), depicting African American heroes. Soon, African American, Hispanic, and Anglo artists were involved in projects that brought together multiple artists, often with the addition of untrained community-area adults and teenagers, through such organizations as the Chicago Mural Group, the Public Art Workshop, and Latino artists of the Movimiento Artistico Chicano, through the 1970s and beyond. While some of the mural walls have institutional settings, others were painted on the train embankments that run through the neighborhoods. The work ranges from exaggerated naturalism inspired by Diego Rivera and his contemporaries to graffiti -like pieces that reflect the artists' origins as subway “taggers.”

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.