|

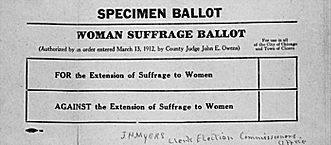

Woman Suffrage Sample Ballot, 1912

|

Feminist movements promote gender equality and oppose the perpetuation of gender discrimination in economic, political, legal, and social structures. In Chicago, such feminist organization began with the Woman

Suffrage

Party of

Cook County,

incorporated in 1912 with Charlotte C. Rhodus as president and dedicated to securing total political equality for women. Another early element of the feminist movement in Chicago was the birth control movement. Chicago-area feminists argued that the lack of legal, easily accessible birth control information and devices discriminated against women. The Chicago

Women's Trade Union League

(CWTUL) demanded birth control information as a democratic right for all women and disseminated such information through its birth control committee, headed by Rachelle Yarros. Yarros and the CWTUL persuaded the Chicago Woman's Club to organize a birth control committee in 1915. In the 1920s, the Parents' Committee worked to defeat laws then being proposed to prevent licensed physicians from dispensing birth control information. In 1923, the committee tried to set up a

clinic

in Chicago where poor women could receive such information, but the Chicago Health Department refused to issue the requisite license. The committee turned instead to promoting birth control centers that functioned inside doctors' offices and founded the Illinois Birth Control League to set up such facilities, which eventually became Planned Parenthood centers.

Feminist ideals also inspired a series of

Women's World Fairs

(1925–1928), where women exhibited their achievements in the arts, literature, science, and industry. The fairs showcased women's accomplishments, but they also served as a venue in which women could inform each other about careers and jobs.

Mabel Vernon Addressing Crowd, 1916

|

Feminist movements waned in Chicago thereafter, as they did across the country, reviving during the 1960s with new movements seeking to use law and legislation to overturn institutionalized political and economic inequality. In 1963, Chicagoan Esther Saperstein introduced a bill into the state legislature to create a Commission on the Status of Women in conjunction with comparable national legislation. In 1967, feminists met in Chicago to organize chapters of the National Organization for Women, whose recently adopted Bill of Rights called for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, maternity rights in employment and Social Security benefits, equal job training opportunities, and women's right to control their reproductive capacities. Chicago women also organized chapters of the National Women's Political Caucus, the Women's Equity Action League to help women file discrimination charges, and the National Black Feminist Organization (renamed the National Black Feminist Alliance) to fight both racism and sexism.

The 1960s also produced a new-wave feminist movement called Women's Liberation, which argued that women suffered both personal and political oppression in a male-dominated society. In 1965, women at the

University of Chicago

organized one of the country's first campus groups focused on this issue. Chicago feminists then founded the

Chicago

Women's Liberation Union

(CWLU) to raise women's consciousness of their oppression, and from 1974 until its demise in 1981 the National Black Feminist Alliance was such a consciousness-raising group for

African American

women in Chicago. The CWLU argued that fighting women's oppression required radical alteration of prevailing economic, social, and political structures. The CWLU and other feminist organizations at the time also proposed to operate in a women's cooperative, “democratic” style as opposed to what they called a men's competitive style.

The feminist movements of the 1960s also concentrated on achieving reproductive and sexual freedom. Feminists demanded affordable child care, birth control and abortion on demand, more attention to women's health needs, rape crisis centers, and women's shelters. Their efforts resulted in the municipal Rape Treatment Center Act of 1974, which established rape treatment centers in city

hospitals.

Feminists were also prepared to defy the law, forming an underground organization (“

Jane

”) to provide abortions when they were still illegal in Illinois.

Chicago Women's Liberation Union

|

Economic equality was also a goal of feminist movements from the 1960s onward. Unlike many women's movements earlier in the century, which had often favored protective labor legislation for women, the new feminist organizations emphasized gender equality in the workplace. The Coalition of Labor Union Women was formed in Chicago in 1974 to give union women access to leadership positions denied in the male-dominated union structure, to help union women overturn discriminatory insurance rates and pension benefit deductions, and to secure maternity leave. Women Employed worked in Chicago to fight hiring and job discrimination for nonunion women. The Feminist Writers Guild, organized in the 1980s, sought similar equality of access for female writers.

Feminist collectives, some of them lesbian or at least closed to men, and periodicals also emerged. Periodicals included

Womankind,

published in the early 1970s by the Chicago Women's Liberation Union;

Mountain Moving,

published later in the decade by the Mountain Moving Collective in Evanston;

Sister Source,

subtitled “a midwestern lesbian/feminist newspaper,” and published briefly in the 1980s; and

Catalyst: Chicago Womyn's Paper

(1980). The collectives and these periodicals were a manifestation of some Chicago-area feminists' desires by the late twentieth century to free women from male domination in a patriarchal society by removing themselves as much as possible from control by men in all areas of their personal and public lives.

Maureen A. Flanagan

Bibliography

Cott, Nancy.

The Grounding of Modern Feminism.

1987

Payne, Elizabeth.

Reform, Labor, and Feminism: Margaret Dreier Robins and the Women's Trade Union League.

1988.

Schultz, Rima L., and Adele Hast, eds.

Women Building Chicago: A Biographical Dictionary.

2001.

|