| Entries |

| C |

|

The City as Artifact

Next

|

|

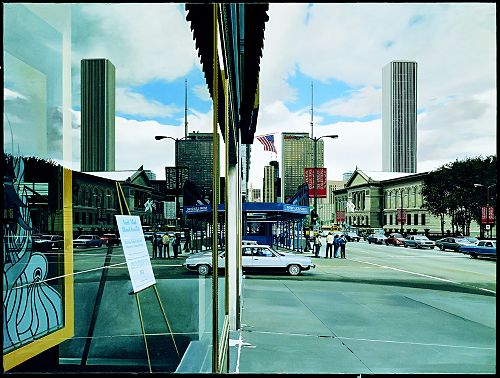

Chicago’s artifact assemblages exist in two main forms: (1) as artifacts that can be found in situ (still in place), like Leonard Volk’s Stephen A. Douglas Memorial (1881), with "The Little Giant" standing atop a 46–foot marble column overlooking the Illinois Central Railroad right–of–way that he successfully lobbied Congress for in 1853; and (2) as extant artifacts in museums, historical societies, libraries, and other cultural institutions, like the Richard Estes painting Michigan Avenue with a View of the Art Institute.

In the first instance, metropolitan Chicago can be understood as a massive, outdoor museum without walls, a historical landscape accessible to residents and visitors any time, day, or season. Repositories that collect and curate a city’s cultural memory, on the other hand, display their material culture (an archaeological term used here as largely synonymous with artifacts) in a more restricted and manipulated context. Together, the city and its repositories provide historical information and insight for understanding Chicago as a collective (and collected) artifact of past and present urban life. Together, they are the result of innumerable individual and communal decisions made by surveyors, land speculators, homeowners, insurance companies, real–estate developers, artists, zoning boards, investors, architects, city councils, urban renewal ("removal" to some) experts, individual and corporate businesses, engineers, demolition contractors, architectural firms, and city planners.

|

In the past decade, archaeologists themselves have endorsed such an approach in studying the American landscape. "Archaeological methods can profitably be applied to any phase or aspect of history," argues Grahame Clark. "A coherent and unified body of subject matter entirely appropriate to the archaeologist," writes James Deetz, "is the study of all the material aspects of culture in their behavioral context, regardless of provenance." Applying the archaeological methodology that Clark suggests to the range of material data Deetz wishes to survey, contemporary archaeologists have shown how important information and insight about human behavior, past and present, can be extracted from urban material culture data without necessarily having to physically excavate it. Historical and cultural geographers concur with this assumption. The student of the cultural landscape is a kind of contemporary archaeologist, with somewhat different materials, similar methods, and nearly identical motives. In addition to its obvious debts to archaeology as traditionally conceived, above–ground archaeology borrows much of its theory and practice from related fields such as art history, cultural geography, architectural history, toponymy, history of city and town planning, urban folkways research, and the history of technology.

Geologic/Geographic Influences

Chicago, like several of its nineteenth–century economic rivals (e.g., Cincinnati, St. Louis), is in part the way it is because of where it is. The glacial waters of what geologists (and some pre–1800 mapmakers) call Lake Chicago (now Lake Michigan) found their way through the drainage divide via two valleys, or sags, en route westward to the Mississippi, recognizable today as the Calumet Sag Channel and the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal.

As the ice sheet retreated irregularly, it occasionally paused long enough to permit shore currents to create spits, bars, islands (surviving in place names such as Stony Island and Blue Island), and beaches, as well as a spoke–like pattern of drainage beds radiating out from the mouth of the Chicago River. In later times, these sandy strips were the only well–drained ground in the spring, and the indigenous peoples used them for overland travel when the surrounding area was waterlogged. In the city plan, some of the major streets that deviate from James Thompson’s original grid plan–such as North Clark Street, the appropriately named Ridge Avenue, and Milwaukee and Vincennes Avenues–are fossils of these glacial formations and Indian pathways.

|

Landscape Vegetation

In a city whose very name derives from an Indian reference to wild garlic (stinking onion) and whose Latin motto (Urbs in Horto) promotes "a city in a garden," the above–ground archaeology student should expect evidence of how past plantings continue in the present urban environment. The city’s parks, botanical gardens, estates, conservatories, cemeteries, forest preserves, and arboretums, despite their seeming naturalness, betray human hands on the land. Some of their landscape authors are nationally famous: Frederick Law Olmsted (Jackson and Washington Parks, 1872; the suburban plan for Riverside, Illinois, 1869); Ossian Cole Simonds (Graceland Cemetery, 1878); and Jens Jensen (Garfield, Humboldt, and Douglas Parks, 1906–1910). The placement, size, design, and vegetation in their artful yet changing collections of plants demonstrate a perennial issue in human history: the relationships between nature and culture.

Chicago’s parks illustrate a miniature history of this relationship and also reveal the interconnections between plants and politics. Compare, for instance, the pleasure garden park (e.g., Jackson Park) of the 1850–1900 era; the Progressive reform park (e.g., Pulaski Park), first appearing about 1900 to 1920; followed by the recreational facility park (e.g., Seward Park), first developed in the 1930s.

In addition to these formal, public landscapes, one also finds vernacular "natural" material culture throughout the Chicago region. For instance, well into the twentieth century, Indian trail trees, like the one at 630 Lincoln Street in Wilmette, survived in northern Illinois. Potawatomi Indians bent or buried young tree sprouts or saplings to indicate the direction of their travel routes east and west, to designate sources of fresh water, and to mark the path to the Chicago Portage.

In a highly urbanized area such as metropolitan Chicago, many examples of the city’s early plants survive only in the area’s place nomenclature. Consequently, the alert above–ground archaeologist must be a recorder and interpreter of such data. Often such names are small time capsules containing linguistic, historic, geographic, and folkloristic information about local history.

For instance, those who fly into O’Hare Airport in Chicago have baggage tags labeled "ORD." That abbreviation recalls not the name of the person (World War II flyer Edward O’Hare) for whom the airport is named, but its former land use as a productive fruit–growing region known as Orchard Place. Samuel J. Walker, a Kentuckian who moved to Chicago and subsequently bought up much of the land around Reuben Street from Madison to 12th Street, decided to rename the street Ashland to honor his native state’s political hero, Henry Clay, whose Kentucky home was known as Ashland. Warner left still another marking on the land when he planted both sides of his residential avenue with rows of white ash.

Street and Road Names (Histories)

Streets–be they boulevards or parkways, alleys or avenues–are a city’s conduits of people and products. Chicago’s commercial/retail/tourist "Main Street" has shifted over the city’s history from Lake to State to Michigan. Residential avenues of affluence have also migrated: from South Michigan Avenue to Prairie Avenue to North Lake Shore Drive to suburban lanes.

Street names often commemorate the presence of earlier peoples in a region (Chippewa, Illinois, Potawatomi); the first people on a city block (Kinzie, Huey, Farrell); the first people on the block who developed adjoining blocks (Diversey, Belden, Palmer). As might be expected, in Chicago’s toponymy we find numerous city fathers (Ogden, Damen, Elston); heroes (Lincoln, Altgeld, Cermak); and builders (Jensen, Burnham, Mies van der Rohe).

|

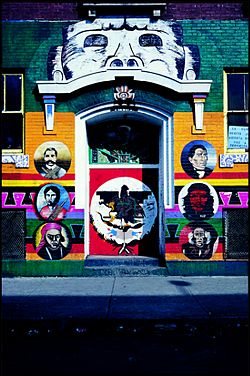

Mural art, almost always public and frequently political, provides a range of historical evidence for the city observer. Chicago abounds in striking examples. For instance, neighborhood ethnicity is portrayed in William Walker’s History of the Packinghouse Worker (1974) on the Charles A. Hayes Family Investment Center; I Welcome Myself to a New Place (1988), by Olivia Gude, Marcus Jefferson, and Jon Pounds, is a history book on an underpass wall in Pullman; Marcos Raya and others depict Latino history on the front entrance of Casa Aztlan, a local community center at 1831 S. Racine in Chicago’s Pilsen district, formally a Czech neighborhood now inhabited by Spanish–speaking Americans. On the Northwest Side, the Humboldt Park murals relate the past of a German community that is also commemorated in city streets elsewhere named Goethe, Schiller, and, of course, Humboldt Boulevard and Humboldt Drive.

|

|

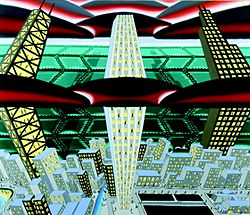

In Chicago, typical time collages lend themselves to a variety of personal explorations. One can walk up or down Dearborn Street (from Congress to Wacker or the reverse), carefully looking left and right to see a century of modern office/skyscraper designs. Another approach is to follow the Chicago River’s course, remembering two things: first, a definition of material culture is "all artifacts are a manipulation of nature," and originally the Chicago River emptied into Lake Michigan, but human engineering reversed its natural course in the second half of the nineteenth century; second, Chicago boasts more moveable bridges than any city in the world–46 of varying types and sizes. One might also position oneself at the corner of Chicago and Michigan Avenues and, turning in a circle, note the diverse land uses of the Chicago Tower and Pumping Station (1866, 1869), the Fourth Presbyterian Church (1914), the John Hancock Center (1969), the Palmolive Building/Playboy Building (1929), and Water Tower Place (1976).

|

Urban Shards

To the archaeologist who "does the dirt" for his or her data, a shard is a fragment of material culture. Above–ground archaeology shards include what art historian George Kubler calls "prime objects" and archaeologist Robert Ascher labels as "superartifacts"–that is, famous material culture icons of the Chicago built environment. Among these shards are the city’s central transit track, created in the 1880s and popularly known as "the Loop"; the Jane Addams Hull House (1889); the Frank Lloyd Wright Robie House (1906–9); and the nation’s first MacDonald’s fast–food restaurant (1955) in Des Plaines.

Above–ground archaeologists also use the term "shard" in its traditional meaning: an incomplete piece, part, or physical remain surviving from the past. In an urban complex such as Chicago–once described by Carl Sandburg as continuously being "built up" and simultaneously "torn down"–the city’s physical past is most often piecemeal. A lonely 1879 Union Stock Yard Gate at 850 West Exchange stands bereft of its nineteenth–century context. Twin equine heads on a Pullman gasoline station (11201 S. Cottage Grove Avenue) recall the building’s original use (ca. 1881) as a livery stable. The Board of Trade Building (141 W. Jackson Boulevard) provides a hybrid view of the architectural, sculptural, and interior design preferences of the art deco 1930s in comparison with the postmodern ambitions of the 1980s. The remodeling (1980) of the Mergenthaler Linotype Building (531 S. Plymouth Court) includes a modern colorful facade plus a playful incorporation of a facade section of Tom’s Grill and Sandwiches, a former adjacent eatery, as a sculptural objet trouvé. Even the Chicago Historical Society has had its migrations and additions–from being headquartered in an 1892 Romanesque building (still extant at 632 N. Dearborn and currently a nightclub) to a 1932 Colonial Revival structure (North Avenue and Clark Street) to which a modern International Style addition was affixed in 1988.

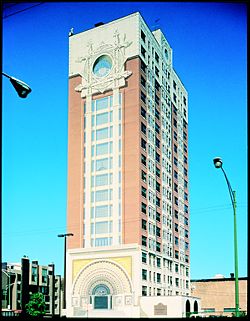

Urban shards can also result from deliberate attempts to embellish artifacts. In addition to its homage to medieval Gothicism (particularly the Rouen Cathedral in France), Chicago’s Tribune Tower (designed by Howells & Hood, 1925) features a stone screen depicting characters (a howling dog and Robin Hood figure) that serve as visual references to the architect’s surnames. As Chicago’s retort to New York’s Woolworth Building (1913), the tower also features, on its lower elevations, an extravaganza of assorted building pieces from well–known structures throughout the world, including a fragment of the Great Wall of China.

|

Chicago’s often tardy historic preservation movement has yielded other urban shards. Many of Louis Sullivan’s buildings have been demolished, but fragments of his work enjoy a second life; for instance, the main entrance to his Stock Exchange Building (which Alice Sinkevitch calls the "wailing wall of the city’s preservation corps") has been relocated to the grounds of the Art Institute at Monroe Street and Columbus Drive. The Art Institute also salvaged Sullivan’s exquisitely stenciled Trading Room and reconstructed it as, perhaps, one of the first commercial period rooms in the United States. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art took home an interior Sullivan copper staircase to display in its American Wing.

The ultimate Chicago tribute, at least to date, to the architectural shard, is Pauline Saliga’s museum exhibition and published checklist, Fragments of Chicago’s Past: The Collection of Architectural Fragments at the Art Institute of Chicago. Innumerable building parts from Chicago, once in situ, are now in museum. Among the more intriguing relics now ensconced in the Art Institute are an engaged capital from the 1887–88 Church of the Covenant; a playful fish ornament from the base of the 1907–8 Oliver Building; and the study model for the head of a sprite for the 1913–14 Midway Gardens.

Historical Markers

|

Historical markers and monuments erected outside a community’s museums, historical societies, and other cultural institutions also have a double existence. First, they provide the above–ground archaeologist with three types of visual/verbal information: (a) about a vanished historic site (e.g., the brass markers embedded in the pedestrian sidewalks on the southwest side of the Michigan Avenue Bridge, which outline the perimeters of Fort Dearborn between 1803 and 1816; (b) about an event (e.g., the plaque on the Jackson Boulevard corner of the Continental Illinois National Bank Building, which notes that in 1883 an association of railroad executives met in Chicago and voted to adopt Standard Railway Time for the entire country); or (c) about an individual (e.g., the sculptures of Abraham Lincoln by Augustus Saint–Gaudens: the "seated" Lincoln in Grant Park [1908] and the "standing" Lincoln in Lincoln Park [1887]).

Like these examples, most historic markers are deliberately celebratory. The four stars on Chicago’s flag, for example, mark four events in the city’s material culture history: its founding, the fire, and two world’s fairs. The Marquette Building (1893–95) interior honors the 1674–75 expedition of Jacques Marquette in an ensemble of sculpture, mosaic, and bronze. In the Second Franklin Building (720 S. Dearborn Street), one finds Oskar Gross’s colorful mosaic murals depicting the history of printing.

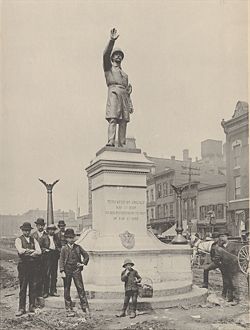

A few of Chicago’s historical monuments, however, have been artifacts of controversy and contest. Consider the tempestuous history of the historic site known (depending on one’s politics) as the Haymarket Square Riot, Massacre, Bombing, Affair, or Anarchy. The only nearby tangible reminder of the 1886 disturbance is the sculpture now at the Timothy J. O’Connor Police Training Academy (1300 W. Jackson Boulevard). A police officer, his arm upraised, restrains an invisible mob, commanding peace, "In the name of the people of Illinois." There has been, however, little peace surrounding this icon of order. Its plaques at the base were stolen in 1903. Later, a streetcar motorman rammed into the statue, claiming he hated to look at it. Moved to Union Park in 1928, the sculpture remained unmolested until the civil turbulence of the 1960s, when it was defaced with black paint and twice bombed. At one time, the sculpture was placed under 24–hour guard and moved to Central Police Headquarters, from which it was transferred to its present site in 1976.

|

|

A region’s cemeteries contain historic monuments to personal histories. The above–ground archeologist looks at them as documents of cultural geography, public sculpture, and historical markers. To be sure, the rich and famous are frequently most prominent, often trying to best each other with gigantic mausoleums in death as they did with their ostentatious mansions in life. In Chicago’s many cemeteries, two stand out: the Couch Mausoleum in Lincoln Park and the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe grave in Graceland Cemetery. In the latter site, Chicago’s most famous architectural modernist lies under a single rectangular black granite slab parallel with the earth–a horizontal curtain–wall skyscraper in miniature.

Few know who the Couches were or why they are still interred in a city park. Ira Couch built Tremont House, an early Chicago hotel. The further explanation as to why the mausoleum has survived since Ira’s death in 1857 is important to thinking of the city as artifact, a space crafted by both private and public decisions. The family tomb is where it is for three reasons: (1) present–day Lincoln Park was once a municipal burying ground (from which the Couch Mausoleum is the only extant above–ground tomb); (2) when park officials demanded the Couches remove their deceased kin to make way for the park, they refused; and (3) when the issue came before the Illinois Supreme Court, the justices ruled to let the Couches rest in peace.

To consider the city as a laboratory recalls Chicagoan John Dewey’s advocacy of the laboratory school–an artifact still extant on the University of Chicago’s campus. To this author, it also prompts remembering Dewey’s insistence that "all history is local history." So believes the above–ground archaeologist. As with the below–ground archaeologist, the researcher who works primarily above ground does not solve every historical riddle in the field. Indeed, above–ground archaeology cannot be done without the data we normally find in local and city libraries, archives, and municipal record offices. The extant cityscape, however, always beckons. The past is visual as well as verbal. It survives in space as well as in time. "Reading the landscape is a humane art," geographer D. W. Meinig reminds us, "unrestricted to any profession, unbounded by any field, unlimited in its challenges and its pleasures."

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.