| Entries |

| S |

|

Sunday Closings

|

|

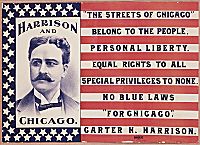

The city and state's closing laws, however, proved unpopular with Chicago's Irish and German immigrants. German Americans, for example, were accustomed to attending beer gardens with family entertainment on Sundays. When Mayor Levi Boone attempted to enforce the law in 1855, the ensuing Lager Beer Riot left the Sunday law a dead letter in the city. Less than two decades later, Mayor Joseph Medill attempted to enforce the Sunday closing law at the request of a group of Protestant temperance advocates. His unsuccessful campaign mobilized Chicago's Irish and German voters against the law, and the city amended it in 1874. The new city ordinance allowed businesses to open on Sunday providing all doors and windows that opened onto public streets were closed or covered. The city law provoked contention over whether it superseded the state Sunday closing law, and in 1909 the Illinois Supreme Court affirmed that the state law was operative in Chicago. By that time the movement for Prohibition had gathered momentum in the state. Although the city allowed Sunday drinking by the mid-1870s, it prohibited selling goods on sidewalks on Sundays, and in 1883 the city banned Sunday street peddling.

|

The most spectacular struggle over Sunday closing in Chicago occurred when city organizers sought federal support to host the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. Effective petitioning by Protestant church leaders ensured a Sunday closing requirement in the fair's 1892 enabling legislation. The fair's directors filed suit and won a partial victory. Although the fair opened on Sundays, no machines were allowed to operate and most exhibits remained closed.

Two state laws, both enacted in the 1930s, defused some of the moral and labor questions that had sustained the state's 1845 Sunday law. The 1934 Liquor Control Act, passed in the wake of Prohibition, prohibited alcohol sales on Sundays unless allowed by local government. The second law, enacted in 1935, specified that employees receive a day of rest each week and advance notice when required to work on Sundays. By 1963 the last section of the 1845 Sunday law, which forbade disturbances of the peace on Sunday, had been repealed. In its place the state prohibited specific activities, including horse racing and automobile sales.

The Encyclopedia of Chicago © 2004 The Newberry Library. All Rights Reserved. Portions are copyrighted by other institutions and individuals. Additional information on copyright and permissions.