|

World's Parliament of Religions, 1893

|

Chicago has been and remains a world-class religious center with

global

influence. It has no major shrine or global headquarters and thus is not in a class with Rome and Jerusalem, Mecca or Benares. Nonetheless, for the past century and a half, it has served as a base for individual citizens and religious groups of many sorts who have sought to change the way moderns think about and pursue spiritual ends. Even when following more conventional lines, Chicagoans have had considerable influence on believers, both nationally and internationally.

The most vivid symbol of that centrality appeared in 1893. During the

World's Columbian Exposition,

several enterprising Chicagoans invented and staged a

World's Parliament of Religions.

This first modern spiritual “fair” exposed publics to representatives of world religions. One might picture the Parliament as a magnet that drew spiritual energies and people to Chicago and, immediately thereafter, propelled many to their home bases, ready to think differently from before about how religions thrive and interact.

Spiritual heirs of those original parliamentarians gathered a century later, again in Chicago, for a centennial observance in 1993. This observance not only led people to look backward to the good old days of 1893. It was designed to encourage them to look forward and outward, to give new impetus to interreligious exchange. This occurred at the end of a century in which religiously inspired conflict was killing people from Northern Ireland to South Africa, from the Middle East to the Asian subcontinent. The repeat observance was not as pathbreaking as the original had been, given that many of the 1893 participants had appeared more exotic to each other, as well as to Chicagoans and Americans at large. But the 1993 event did symbolize the interest Chicagoans have in seeing their city as a spiritual magnet and impelling force.

Stephen Beggs on Circuit Riders, 1834

|

Most of Chicago's religious influences have been somewhat more traditional, but they have reflected enterprise and ambition. Two themes that vivified the Parliament have persisted. One seeks to promote interaction, to make the city a crossroads. The other has people presenting their own religions to others and to the nonbelieving world as being the true, or the best—which means something to which to be converted. The physical location of the metropolis helped and helps promote the former. Once lake traffic and

railroads

poised Chicago as a place for the crisscrossing of influences; those who had ideas to try out on others could hardly avoid the city at the bottom of Lake Michigan, and they found it attractive.

The conversion efforts have been more visible and vivid. However much

Roman Catholics

and others might have set out to win new members, in the United States people associate proselytizing, evangelizing, and converting with evangelical—generally “conservative”—

Protestantism.

The three best-known and most inventive modern Protestant evangelizers, Dwight L. Moody, Billy Sunday, and Billy Graham, began their decisive work in Chicago and, in the first two cases, made it their central base.

Billy Sunday, 1915

|

What was it about Chicago that led entrepreneurs of the spirit to embark on missions to convert there? Of course, it might have been pure coincidence that brought the three here. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Moody came as a young businessman who was soon found to be a success at “soul-winning.” By the start of the twentieth century, Billy Sunday had left the baseball diamond, had been converted at the

Pacific Garden Mission,

and had begun moving from a Northwest Side pastorate to a flamboyant set of missions nationwide. As the middle of the twentieth century approached, Billy Graham, the world's best-known evangelist ever, began his worldwide set of “crusades” during his years at suburban

Wheaton College.

He became a pastor of a church in nearby

Western Springs

and gained wider reputation as a budding preacher in Youth for Christ, a movement that made news chiefly in downtown venues. In all three cases, one can write off the effects of coincidence by citing the accident of charisma and talent among such individuals. But they did find Chicago a most congenial metropolis.

So did their opposite numbers, the theological modernists. Late in the nineteenth century many of the traditional Protestant bodies produced a generation of critical and progressive thinkers. They used the new tools of biblical criticism to pursue the historical background of Christianity. They welcomed evolution, the scientific theory that so appalled conservatives. Their outlook on the future was optimistic; they would help “bring in the Kingdom of God.” Chicago looked like a good place to start.

Rockefeller Chapel, n.d.

|

Many of the modernists influenced the theological world through the new

University of Chicago,

founded by Baptists but open to others. William Rainey Harper, the first president, and the dean of his university's Divinity School, attracted scholars and sent forth students to spread the modernist word. They helped force the issue of fundamentalism and modernism in the denominational battles of the 1920s. Chicago had a hand in the legal fray over the legitimacy of teaching evolution in the public schools in the Bible belt. In a famed trial in Tennessee in 1925, University of Chicago modernists coached the defenders of indicted teacher of evolution John Scopes, while Chicago fundamentalists backed William Jennings Bryan, lawyer for anti-evolutionists, against the legal attacks by Chicagoan Clarence Darrow, a liberal lawyer with a religiously agnostic outlook.

The clash of these two schools of thought represented but one of many events that helped color the religious scene nationally and beyond. Their leaders helped create an image different from the one Chicago has often presented. The city, known for its material achievements and its reputation as a sometimes cruel center of commercial and industrial competition, has also been recognized as a locale where spiritual endeavors have prospered, and a brief canvass of some of them will help focus this counterimage.

For many Chicagoans religion means and has meant

religious institutions

and what they represent and accomplish. Any survey of religious influences emanating from their city therefore must focus on the chronicling of church and synagogue life.

Journal of Father Jacques Marquette

|

The beginnings of organized religion around the site of

Fort Dearborn

during the 1830s were at the hands of English-speaking Protestants who pioneered in placing churches on the frontier. Before the end of the century these dominant Protestants found their place and position challenged by Protestants from the European continent—Lutherans and Reformed in particular—and then both kinds of Protestants found themselves outnumbered by Roman Catholics. Catholics had explored the Chicago region as early as 1673, but maintained no institutional presence after the closing of the

Mission of the Guardian Angel

in 1699. In the nineteenth century the first priest was assigned to Chicago in 1833, the year it incorporated. Chicago's Catholics were at first English-speaking, chiefly immigrants fleeing Catholic Ireland after devastating famines when potato crops failed. Immigrants from the European continent followed, speaking

German,

Polish,

and

Italian.

Greeks, Russians, and others added

Eastern Orthodox

churches to the mix. Immigrants stamped their ethnicity on Catholicism, a stamp that was widely observed by Catholics in other cities as they set out to cope with a new environment.

Chicago Hebrew Institute Athletics

|

Chicago

Judaism

might not have had as much national influence as did Judaism in the New York area, and it developed no theological school to carry influence as did those that flourished in New York and Cincinnati. Yet Chicago became a center for the Midwest dispersion. By the 1880s,

Jews

were well established in Chicago. These “Reform” Jews especially from Germany were called to welcome and accommodate poorer Eastern European Jews from ghettos and shtetls, refugees from pogroms that began in the Pale of Settlement along Russia's western border after 1881. The legacy: Chicago served as a model for other developing metropolises, most of them having ethnic and religious mixes that matched, on smaller scales, what the new Chicago immigrants were inventing.

After the Catholic immigrations, the greatest change came during and after the two world wars and in the prosperous postwar period, when

African Americans

by the many thousands migrated, especially from the rural South. They brought with them Methodist, Baptist, and later Pentecostal faiths associated with the South. They made their homes in the South and West Sides of the city, areas which most whites left. Catholicism and white Protestantism became increasingly suburban phenomena, although Catholic parishes persisted and Catholicism remained the majority faith in the city.

Olivet Baptist Church, 1952

|

National leaders of the black churches made Chicago a base of operations at some stage or other of their career. These included Joseph Jackson, longtime president of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc., and Martin Luther King, Jr., who made the city the northern base for efforts by the Southern Christian Leadership Council during the

civil rights

struggle up to his death in 1968. In the middle of the twentieth century an innovation in African American religion came to be recognized worldwide. Elijah Muhammad built the

Nation of Islam

(sometimes called “Black Muslims” in popular media) into a mass movement attracting thousands of African Americans to Islam and black nationalism.

The first Protestant churches were housed in impressive edifices expressive of the prosperity of leading members. Until the middle of the twentieth century, most of Chicago's elites were Protestant, and they helped subsidize great sanctuaries featuring, for example, Tiffany windows that have become landmark features in the city. Architecturally, however, it was Catholicism that turned the cityscape into a churchscape, and it is from Chicago Catholic experiments that influence spread. Wherever observers had vantages for looking at the skyline, they would see a crowd of steeples and domes, churches that often reflected the architectural styles of the old country or that aspired to make new statements by towering over the

bungalows

of the neighborhoods. The first Catholic church building in America considered “modern” was St. Thomas the Apostle in

Hyde Park,

designed by local architect Francis Barry Byrne.

Unity Temple, 1913

|

When one reckons Chicago influence on religious architecture, however, the eye falls chiefly on buildings of Protestants and Jews that were designed by world-renowned architects who are identified with Chicago. The buildings they designed in Chicago might not have been their most noted, but by the force of their personality and the weight of their talents they called attention to their work here. These included Frank Lloyd Wright, who created a classic Unity Temple in

Oak Park;

Mies van der Rohe, who planned a less-distinguished IIT chapel at Illinois Institute of Technology; Adler and Sullivan, who designed KAM Temple, which later became Pilgrim Baptist Church; and Louis H. Sullivan, who left a landmark in Holy Trinity Cathedral of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Spells Brothers Gospel Singers, n.d.

|

The Chicago influence has spread to other arts as well. One can make the case that “

gospel”

and “soul,” major African American contributions to religious music, originated in Chicago. Thomas Dorsey was the pioneer of gospel music, and singers like Mahalia Jackson helped carry it to the rest of the nation and much of the world. Long before that, Billy Sunday's musical partner, Homer Rodeheaver, influenced the kind of evangelistic gospel song popular in revivalistic Protestantism.

Northwestern University's school of music fostered world-acclaimed classical church music, for example through the compositions of Leo Sowerby. GIA Publications, under Catholic auspices, and Hope Publishing in Wheaton, an evangelical house, have encouraged and published music that shapes styles across the nation and wherever American religious influence spreads.

International Eucharistic Congress, 1926

|

While Protestants, whatever their church polity, tended to depend on and encourage the lay initiative of congregations, which also meant that in most ways the congregations “owned” the properties, Catholic polity made provision for a different arrangement. This form, called “Corporation Sole,” meant that all diocesan church properties of the parishes were legally under the “ownership” of the archbishop. These clerics became powerful presences in Chicago, often working with city hall (or criticizing it), just as in the neighborhoods priests and precinct captains tended to be partners of sorts. Some of the archbishops, usually named cardinal, were men of enormous personal power and the skill to wield it. Thus George William Cardinal Mundelein, archbishop from 1916 to 1939, who attracted a Eucharistic Congress to Chicago in 1926—an event that paraded the prosperity and numbers within Chicago Catholicism for the world, including mass gatherings of 125,000 people at

Soldier Field

—built a suburban campus in what became

Mundelein

and presided over much parish building and growth during his tenure.

Other cardinal-archbishops became known not for Corporation Sole power but for scholarship (e.g., Albert Cardinal Meyer, archbishop from 1958 to 1965, who was influential at the Second Vatican Council, 1962–1965) and works of justice or examples of piety (e.g., Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, 1982–1996, the first of these hierarchs to become widely accepted as a mentor and example to non-Catholics of the city).

Religion in Chicago has not been housed only in church, synagogue, and mosque. The city has attracted and nurtured many

seminaries

and theological schools, some of them related to universities, as at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago; others “clustered,” as in a Hyde Park coalition; and some in the form of a conglomerate or merger of many small theologates, as at the Catholic Theological Union, or a merger of half a dozen seminaries, as in the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago. Priests and ministers from these schools have been at home with the changing city and have carried Chicago influences wherever they became pastors.

Roman Catholics in Chicago have often been innovators. One of the renowned inventions was the

Catholic Youth Organization,

a

Great Depression

–era creation of Bishop Bernard Sheil (1886–1959). Sheil was a very independent-minded auxiliary who, in the years from the Depression into the prosperous 1950s, put his main energies into raising funds for, administering, and publicizing a movement designed especially to hold the loyalties of young Catholics, mostly from the poorer neighborhoods, and to help them fill their lives. Sheil stressed athletic competition, especially

boxing.

Corpus Christi Church Interior, 1942

|

At midcentury many analysts ranked the

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago

among the most inventive and influential in the Catholic world. Confronting a shortage of priests and nuns just before the Vatican Council II, the laity began to show new kinds of creativity. What came to be called “the apostolate of the laity” revealed Chicago influences, thanks to efforts by local people to promote new understandings of marriage, race relations, and support of organized labor. These “apostles” created literary fronts typified by the Thomas More Association, publisher and seller of books and magazines; St. Benet's bookstore; and various social justice movements and community-building agencies such as the Catholic Family Movement. Almost all of these had national influence.

Chicago has been an ecumenical center for what are called “mainstream” Protestant and Orthodox as well as “evangelical” styles. The only World Council of Churches Assembly—an event held roughly every seven years since 1948—to be held in the United States occurred at

Evanston

in the summer of 1954. On that occasion 502 delegates from 161 member churches were well hosted by Chicagoans and carried new ecumenical impulses to and from the city.

On the evangelical front, the National Association of Evangelicals, founded to gather church bodies that are somewhat more moderate than fundamentalists, has long been associated with

Wheaton,

sometimes dubbed “the evangelical Vatican,” and later operated from suburban

Carol Stream.

The largest and best known of the evangelical Protestant “megachurches,” suburban

Willow Creek Community Church

has had national influence and spawned many slightly smaller replications. Such independent congregations describe themselves as nontraditional and “user-friendly” and use contemporary techniques of market research and

advertising

to promote what members see as historical and biblical Christianity in a new package.

Two magazines symbolize the worlds these organizations embody, and from them the Chicago influence extends worldwide. The more liberal of the two, once quite modernist in outlook, is the

Christian Century.

The evangelical counterpart, founded in the 1950s in part to challenge the other magazine, is

Christianity Today.

Baha'i Temple, 1971

|

What many of the members of all these groups would consider to be marginal or esoteric, the innovative religions that have taken form in the United States, have had presences in greater Chicago, though it is not so strongly identified with these as are places like California. The Theosophical Society has a headquarters and publishes from Wheaton. The

Baha'i

Temple in

Wilmette,

while not the world headquarters of Baha'i, is such a distinctive building that it draws members of that faith and guests from around the world.

Among the once-marginal but now booming and well-known Christian movements developed in this century is Pentecostalism. Most historians associate Topeka, Kansas, and Los Angeles with its founding, between 1900 and 1906. But shortly thereafter the pioneers converged on Chicago, which is often seen as the third “birthplace” of the fastest-growing form of Christianity in many parts of the world. John Alexander Dowie led one of the most influential of the young Pentecostal movements and brought his healing movement and utopian impulses to north suburban

Zion,

which he founded in 1900.

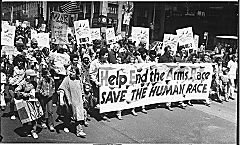

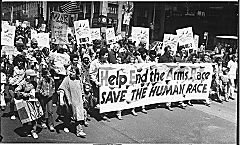

Mother's Day Peace March, 1983

|

Through all these influential experiments and changes, Chicago has retained the image of being the practical, material, competitive culture on one hand and, on the other, a place where the esthetic, spiritual, and often cooperative religious forces could come together to alter the city's harsh reputation and serve the people in it.

Martin E. Marty

Bibliography

Livezey, Lowell, ed.

Public Religion and Urban Transformation: Faith in the City.

2000.

Seager, Richard Hughes.

The World's Parliament of Religions: The East/West Encounter, Chicago, 1893.

1995.

Shanabruch, Charles.

Chicago's Catholics: The Evolution of an American Identity.

1981.

|